Fresh Breezes and Sea Swells Define Optimist Midwinters

On February 19-20, Del Rey Yacht Club in Marina del Rey ran their annual Stephen M. Pitts Memorial/SCYA Midwinters Optimist Regatta. Stephen Pitts was twice Association of Santa Monica Bay Yacht Clubs Junior Yachtsman of the Year. He selflessly mentored younger kids on sailing. Tragically, he passed away from leukemia at age 18.

The Optimist is a 7-ft, 9-in pram similar to a Sabot or El Toro except that it has a sprit rig rather than a triangular sail. More than 150,000 of them are in existence. They can handle a lot of sea-state-related nastiness in the hands of a good skipper. In 1947, Clark Mills first introduced them as a low-cost sailboat for young people aged up to 15. On any given day, hundreds of them are out sailing in New Zealand as part of grade-school classes.

In past years, the normally light-air mid-February event has featured thunder and lightning (a definite no-go), Santa Ana winds, and breezes that nearly blew the kids off the water.

Saturday’s Racing

The 2022 Champ fleet event didn’t have the normal lack of breeze. Saturday began with southwest winds of 6-7 knots at the noon start. After two general recalls, winds increased gradually. The swells followed suit, and by 2:30 close-together swells topped 6 feet. Winds peaked at 15 knots by the fourth and final Saturday race.

The kids took it all in stride and did a terrific job racing, while the race committee boat pitched and lurched as though inside a bounce house. One boat capsized at the top mark.

Sunday’s Outcome

Sunday saw the seas lie down, the sun duck behind clouds, and temps cooling to the 50s by 3:30. A perfect, albeit slightly chilly, sailing day. Three races were recorded on Sunday.

The Green (younger) fleet regatta was held inside the marina. Except for one lamebrain motoring through the kids’ fleet and a coach-assisted rescue, it went well.

In the Champ fleet, 13-year-old Cooper Keeves rattled off six bullets to claim overall honors and win the Red fleet.

Louisa Neumann and Miles Gordon won the Champ White and Blue fleets respectively. The Green fleet winner was Adrian Gerber, who scored four firsts. For complete results, see https://delreyyachtclub.theclubspot.com/regatta/HPAvi5CVUX/results.

USCG’s New Fire Extinguisher Rules Coming Into Effect This April

To the uninitiated, dealing with a boat fire might seem easy: You’re surrounded by water. But we all know that isn’t the solution. Boat fires are a very real danger to you, your passengers, and your boat. Whether your boat is made of wood, fiberglass or composite material, even aluminum or steel, boats are full of flammable materials and will burn very quickly. Even without the flames, the toxicity in the fumes can be deadly. That’s why we all need to carry fire extinguishers on board, and be up to date with the latest rules regarding the correct type for our particular vessel.

New fire extinguisher regulations are going into effect on April 20, 2022, with the major change being that both disposable (non-rechargeable) and rechargeable units that are more than 12 years past their manufacture date are no longer considered serviceable and will need to be replaced with a new extinguisher. And, of course, they need to be the type specified for your vessel length, and be labeled for marine use.

BoatUS has prepared a simple guide that will help you determine if you need to upgrade your equipment.

If you own a boat that is model year 2018 or newer, you may need to replace your fire extinguishers.

- In addition to meeting the carriage requirements for the correct number of extinguishers for the size of your boat, they must be labeled as 5-B, 10-B or 20-B; extinguishers labeled with B-I or B-II only are no longer acceptable.

- Extinguishers must not be more than 12 years old according to the date of manufacture stamped on the bottle.

- You only have to get new ones if yours are no longer serviceable. Good serviceable conditions are as follows:

– If the extinguisher has a pressure gauge reading or indicator, it must be in the operable range or position.

– The lock pin must be firmly in place.

– The discharge nozzle must be clean and free of obstruction.

– The extinguisher must not show visible signs of significant corrosion or damage.

If you own a boat that is 2017 model year or older (between 1953-2017):

- You may keep your extinguishers labeled B-I and B-II as long as they are still serviceable, but

- If there is a date stamped on the bottle, extinguishers must not be more than 12 years old according to that date.

Depending on the size of your boat you may need more than one. Boats less than 26-ft are required to have at least one B-1 fire extinguisher on board. Boats 26- to 40-ft need to have at least two B-1 fire extinguishers on board. If the boat has a USCG-approved fire extinguisher system installed for protection of the engine compartment, then the required number may be reduced. In addition, knowing what to expect, and what to do, is critical if you expect to effectively fight a fire. Each year you need to ensure that your fire extinguishers are in proper working order, and that everyone who boards the boat knows where they are.

See the full guide here.

Here’s a short video produced by BoatUS a couple of years back that discusses some commonly held beliefs about fire extinguishers. You can also go to the BoatUS website find out more about required equipment.

Shearwater Sailing: Building Sailing Skills and Community in Northern California

Upcoming Opportunities:

March 23, Monterey to San Francisco (FULL)

March 26, SailGP viewing and sailing on S.F. Bay

March 29 – April 29, private charter daysails on S.F. Bay

April 8-10, ASA 106 Advanced Coastal Cruising (Offshore)

April, San Francisco Bay Charters

April 30, San Francisco to Monterey (FULL)

For more information and booking visit: https://www.shearwatersailing.net/booking

Sweeps Take a Yankee One-Design Home

Sean Svendsen of The Boat Yard at Grand Marina sent us this photo of Geoff Clerk rowing his classic Yankee One-Design, Flotsam, back to Fortman Marina after they’d unstepped the mast. Sean said, “The boat actually has oarlocks and, as you can see, very long oars. Geoff told me, “It’s much easier to row without the mast in it.” Who would have thought?

There’s something about traditional yachting that always stirs the heart.

The End of the Anchor-Out Era, Part 3

Perhaps the most common complaint about anchor-outs is over damage to the ecosystem — namely eelgrass. There can be no question that boats moored in shallow-ish water, and anchored with a hodgepodge of clumsy tackle, do significant damage to the Bay floor. There can be no question that some, but not all, boats drag anchor during storms each year, with many of them going ashore. Over the years, some but not all anchor-outs have used private marinas as if they were public facilities, which can cost businesses real money to cover the increase in services. But the most common, near-automatic comment Latitude hears about anchor-outs has been, “People living on boats dump their shit into the water.”

“Water quality issues cannot be pegged solely on anchor-outs,” former Richardson Bay Regional Agency harbormaster Curtis Havel told us. “When you look at Richardson Bay and the watershed around it, the first concern is rain and runoff from the road, including fertilizers and old sewer lines. It’s a nonpoint pollution nightmare.” Havel said that during his tenure, the RBRA tested its waters twice a year, and that overall water quality had been improving.

Reports of good water quality are consistent with a 2018 inquiry we made with the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board, following an assertion from a reader that, because of anchor-outs, E. coli was a persistent problem in Richardson Bay. “In recent years, the water quality in Richardson Bay has been pretty good,” a staff member told us; they added, “However, if [an anchored boat] does discharge into the Bay, it would be very hard to detect.”

Vince Weigel, the owner of Eco Marine Pump-Out Services, told us that his company services “hundreds of boatowners on a weekly basis, and we service the anchor-out population gratis. I’ve instructed my operators to pump them out with no questions asked. We are trying to do our part in cleaning up the Bay for the betterment of Richardson Bay.” Weigel acknowledged what most of us would reasonably assume: that many boats do not have fully functioning plumbing systems. “Because of that, [some anchor-outs] use other means of disposing of their waste — like buckets or bags.”

Despite improved water quality, there have been several serious spills over the last 10-plus years, which are often blamed on Sausalito’s aging infrastructure. In March 2021, nearly 100,000 gallons of sewage spilled into Richardson Bay during the course of two weeks; the spill, which was caused by tree roots penetrating a sewer line, resulted in high levels of E. coli, according to the Marin Independent Journal. In January 2008, the Sewerage Agency of Southern Marin (SASM) released 2.4 million gallons of raw sewage on one day, and another 962,000 gallons of partially treated sewage six days later, a Marin County Civil Grand Jury report said.

“In terms of his overall impact on our community and our planet, compare the liveaboard, whom the BCDC would like to regulate, with the non-liveaboard, whom BCDC does not propose to regulate,” wrote Philip Graff in a1985 issue of Latitude questioning the then-developing laws regulating anchor-outs. “It appears that the BCDC and its staff must believe that all liveaboard vessels have unlimited supplies of water with which to create greywater, and that all liveaboards suffer from constant diarrhea.”

Former RBRA harbormaster Bill Price told us that boats on Richardson Bay were “inconsistent” in terms of anchoring-skill levels. “It was always a surprise what you’d pull up: an engine block, or a pile of concrete.” One anchor-out told us that he once saw someone try to use a bicycle as an anchor.

Aerial images have shown severe scarring, or “crop circles,” in eelgrass beds caused by ground tackle. A 2019 report commissioned by the RBRA, which studied the feasibility of an ecologically based mooring field, said that there’s been “considerable damage” to eelgrass habitat as a result of existing mooring practices and locations. “In addition to ground-tackle damage, most vessels within the Bay are in waters too shallow for the vessels moored in them. As a result, vessels drag keels and/or motors on the bottom,” the report said, adding that vessels underway, including dinghy traffic from liveaboard boats, often run through eelgrass beds.

The report also said that anchor-out dinghies did not account for the majority of damage. The frequency of twin-propeller marking makes it more likely that “principal eelgrass damage [is] from larger boats, such as commercial salvage vessels, law-enforcement, and vessel-rescue boats that are either deep draft, or operate at inopportune tidal levels by necessity,” the report said.

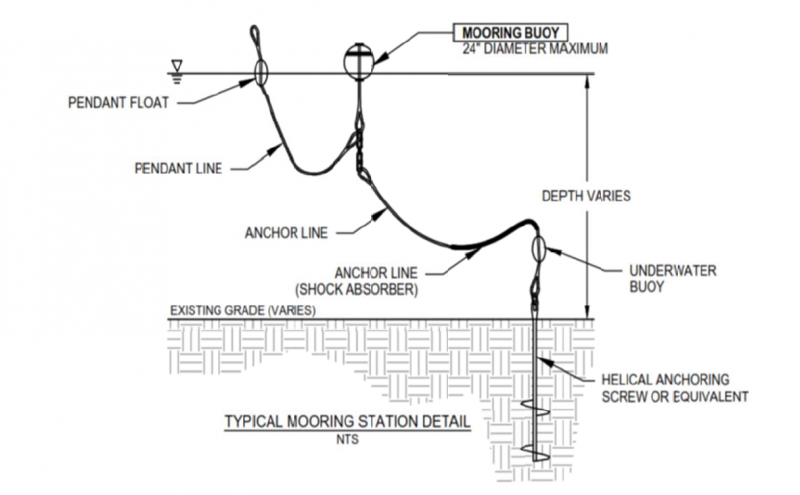

Conservation or eco-friendly moorings suspend tackle above the sea floor, and prevent some of the drag and subsequent scarring associated with conventional setups. Conservation moorings, which are more expensive but also last longer, allow mooring fields to be more more densely packed, because the required radii for moorings using elasticized lines are less than for standard chain moorings, the feasibility report said.

Despite the available technology and numerous proposals, a mooring field in Richardson Bay is still a kind of unicorn — something imagined but never realized. How is it that one of the saltiest cities in one of the maritime capitals of the West Coast cannot agree on a common-sense solution that would be good for anchor-outs, transient cruisers, and the environment, and that would be safer?

To be fair, because the abundance of older and in-need-of-maintenance boats have value as shelter for a growing number of unhoused people, a mooring field could offer easier access to a population that shouldn’t, and probably doesn’t want to, live on the water. Anchoring represents some immediate test to a boat owner’s skill, where a mooring lowers the barrier to entry.

Like so many environmental concerns, the benefits of eelgrass cannot be seen, nor can its benefits be easily measured in our daily lives.

Eelgrass is considered a habitat-forming species. “It’s not uncommon to find a thousand or more invertebrates on a single eelgrass shoot,” Dr. Katharyn Boyer, a professor of marine biology at San Francisco State, told us. “It’s really good food for fish and some birds, and it’s a nursery habitat for juvenile fish. The roots of the plants help to secure sediments, so it’s good at reducing erosion, and is included in living-shoreline restoration projects. Locally, eelgrass can increase the pH of the water, which is good for organisms that form shells. This supports native oyster populations. Eelgrass is also good at storing carbon.”

Scientists have been studying mooring scars in Richardson Bay that no longer have a boat moored in them. “We have started doing some restoration planting in five scars so far in an experimental way, and trying to determine if it is valuable to plant, or if that area will recover on its own,” Boyer said.

The data do seem to suggest that eelgrass beds have grown over the last five years. “Between 2014 and 2019, there’s quite a bit more eelgrass than there was before, but there are still several damaged areas,” Boyer said, stressing that it’s not clear if the growth in the eelgrass population represents a trend, or rather, interannual variations that are tied to fluctuations in rainfall. Eelgrass expands during droughts, and recedes in high-rainfall years.

“We have some bigger concerns than eelgrass, such as taking care of the numerous Superfund sites around the Bay Area,” a former Richardson Bay anchor-out told us in 2018. “Eelgrass is a straw man’s argument — it’s just one of the many excuses to justify dealing with a portion of the population that is undesirable.” (The Marinship — Sausalito’s working waterfront, which is home to hundreds of businesses, several restaurants and many liveaboards — is categorized as a “Non-Priority Superfund Site.”)

Both Boyer and the firm contracted to do the feasibility report acknowledged the importance of finding a balance between the environment and people’s lives. “We are very conscious of the fact that there is conflict, and we’re not advocating for harm to anyone that could result in them losing their home,” Boyer said. “I don’t think anyone out there means to harm the eelgrass. I’m for minimizing the impacts; getting boats out of the eelgrass doesn’t mean that there can’t be moorings anywhere.”

If you’re anchored on Richardson Bay, then you can expect at least one solid storm a year — if not a handful. Boats, their tackle and their owners will be tested, though in many cases, boats are unattended during weather events.

In January 2021, a Norther caused five boats to drag into Schoonmaker Point Marina in Sausalito. An unoccupied 25-ish-ft sailboat dragged into the 40-foot wooden cabin cruiser Salty, which was anchored out. Salty smashed against a dock, broke up, and sank. The owner escaped with a few possessions, but her dog was lost. A Marin waterfront homeowner recently told VICE News that boats that had broken anchor had crashed into the dock or deck of his house “a minimum of 16 times. And that’s not uncommon up and down the street. It happens all the time.”

Several marina operators have told us that, at times, some anchor-outs have used their facilities as if they were public, and that some people were less-than-stellar stewards or neighbors. An East Bay harbormaster told us that, last year, someone dumped a portable toilet into a landscaping planter in the marina. Even objects as seemingly innocuous as garbage dumpsters have become points of contention — one Richardson Bay harbormaster said that that it could cost the marina thousands of dollars a week for the increased trash pickup.

Some longtime liveaboards in Sausalito have told us that these kinds of problems are just the tip of the iceberg. It’s here, at the end of this story and at the end of this era, that we again run the risk of making sweeping generalizations about people. But we also run the risk of not calling out bad behavior and bad seamanship for what it is.

In the end, the anchor-out debate is about a crisis bigger than boats moored on a bay, bigger than this publication, and bigger than the people and agencies who are forced to confront the issue. There is an affordable-housing crisis in the Bay Area, and it can manifest as homelessness, which can lead to mental health issues or drug abuse. It has manifested on the water, and in encampments around marinas in the East Bay. This is not something that the BCDC, RBRA, harbormasters or the police can solve — nor should they be asked to.

We hope for peace, safety, a clean environment, and with luck, just a few well-found, well-maintained boats anchored out on the Bay.

Please click here for Part 1 of this series, and here for Part 2.

Be Prepared for the Martian Invasion— Get Latitude 38 Delivered to Your Mailbox!

February is a short month, as far as the calendar goes, and the Latitude crew have worked double-time to ensure we get the March issue off to the printers in time for your copy to be delivered to your mailbox next week! Of course, to be able to find the magazine in your mailbox, you need to be subscribed. Have you done that? We highly recommend it. Because, what if you go to your usual outlet and find they’re all out of Latitude 38s? Or what if you don’t have time to go get one? Or, what if some crazy Martians come down and take all the copies that are out there in the public spaces, and the only people who retain their copies are those who had them delivered? OK, this last scenario might be a bit extreme, but hey, you never know, truth is often stranger than fiction. And that’s what makes Latitude 38 such a good read. The craziest things happen to sailors (which is OK, because sailors can handle it), and we love sharing those crazy stories in the pages of the magazine.

You know what to do — Subscribe to Latitude 38 and have your copy of the West Coast’s best sailing magazine delivered to your mailbox every month!

By the way, our next edition of Sailagram goes live next week, and there’s still time. If you have any photos you want to share, or if you take some when you go sailing this weekend, email them to [email protected].