The End of the Anchor-Out Era, Part 3

Perhaps the most common complaint about anchor-outs is over damage to the ecosystem — namely eelgrass. There can be no question that boats moored in shallow-ish water, and anchored with a hodgepodge of clumsy tackle, do significant damage to the Bay floor. There can be no question that some, but not all, boats drag anchor during storms each year, with many of them going ashore. Over the years, some but not all anchor-outs have used private marinas as if they were public facilities, which can cost businesses real money to cover the increase in services. But the most common, near-automatic comment Latitude hears about anchor-outs has been, “People living on boats dump their shit into the water.”

“Water quality issues cannot be pegged solely on anchor-outs,” former Richardson Bay Regional Agency harbormaster Curtis Havel told us. “When you look at Richardson Bay and the watershed around it, the first concern is rain and runoff from the road, including fertilizers and old sewer lines. It’s a nonpoint pollution nightmare.” Havel said that during his tenure, the RBRA tested its waters twice a year, and that overall water quality had been improving.

Reports of good water quality are consistent with a 2018 inquiry we made with the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board, following an assertion from a reader that, because of anchor-outs, E. coli was a persistent problem in Richardson Bay. “In recent years, the water quality in Richardson Bay has been pretty good,” a staff member told us; they added, “However, if [an anchored boat] does discharge into the Bay, it would be very hard to detect.”

Vince Weigel, the owner of Eco Marine Pump-Out Services, told us that his company services “hundreds of boatowners on a weekly basis, and we service the anchor-out population gratis. I’ve instructed my operators to pump them out with no questions asked. We are trying to do our part in cleaning up the Bay for the betterment of Richardson Bay.” Weigel acknowledged what most of us would reasonably assume: that many boats do not have fully functioning plumbing systems. “Because of that, [some anchor-outs] use other means of disposing of their waste — like buckets or bags.”

Despite improved water quality, there have been several serious spills over the last 10-plus years, which are often blamed on Sausalito’s aging infrastructure. In March 2021, nearly 100,000 gallons of sewage spilled into Richardson Bay during the course of two weeks; the spill, which was caused by tree roots penetrating a sewer line, resulted in high levels of E. coli, according to the Marin Independent Journal. In January 2008, the Sewerage Agency of Southern Marin (SASM) released 2.4 million gallons of raw sewage on one day, and another 962,000 gallons of partially treated sewage six days later, a Marin County Civil Grand Jury report said.

“In terms of his overall impact on our community and our planet, compare the liveaboard, whom the BCDC would like to regulate, with the non-liveaboard, whom BCDC does not propose to regulate,” wrote Philip Graff in a1985 issue of Latitude questioning the then-developing laws regulating anchor-outs. “It appears that the BCDC and its staff must believe that all liveaboard vessels have unlimited supplies of water with which to create greywater, and that all liveaboards suffer from constant diarrhea.”

Former RBRA harbormaster Bill Price told us that boats on Richardson Bay were “inconsistent” in terms of anchoring-skill levels. “It was always a surprise what you’d pull up: an engine block, or a pile of concrete.” One anchor-out told us that he once saw someone try to use a bicycle as an anchor.

Aerial images have shown severe scarring, or “crop circles,” in eelgrass beds caused by ground tackle. A 2019 report commissioned by the RBRA, which studied the feasibility of an ecologically based mooring field, said that there’s been “considerable damage” to eelgrass habitat as a result of existing mooring practices and locations. “In addition to ground-tackle damage, most vessels within the Bay are in waters too shallow for the vessels moored in them. As a result, vessels drag keels and/or motors on the bottom,” the report said, adding that vessels underway, including dinghy traffic from liveaboard boats, often run through eelgrass beds.

The report also said that anchor-out dinghies did not account for the majority of damage. The frequency of twin-propeller marking makes it more likely that “principal eelgrass damage [is] from larger boats, such as commercial salvage vessels, law-enforcement, and vessel-rescue boats that are either deep draft, or operate at inopportune tidal levels by necessity,” the report said.

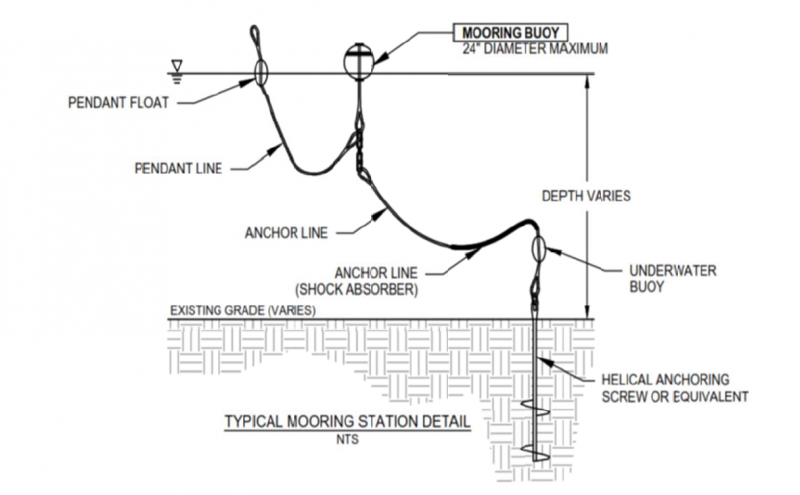

Conservation or eco-friendly moorings suspend tackle above the sea floor, and prevent some of the drag and subsequent scarring associated with conventional setups. Conservation moorings, which are more expensive but also last longer, allow mooring fields to be more more densely packed, because the required radii for moorings using elasticized lines are less than for standard chain moorings, the feasibility report said.

Despite the available technology and numerous proposals, a mooring field in Richardson Bay is still a kind of unicorn — something imagined but never realized. How is it that one of the saltiest cities in one of the maritime capitals of the West Coast cannot agree on a common-sense solution that would be good for anchor-outs, transient cruisers, and the environment, and that would be safer?

To be fair, because the abundance of older and in-need-of-maintenance boats have value as shelter for a growing number of unhoused people, a mooring field could offer easier access to a population that shouldn’t, and probably doesn’t want to, live on the water. Anchoring represents some immediate test to a boat owner’s skill, where a mooring lowers the barrier to entry.

Like so many environmental concerns, the benefits of eelgrass cannot be seen, nor can its benefits be easily measured in our daily lives.

Eelgrass is considered a habitat-forming species. “It’s not uncommon to find a thousand or more invertebrates on a single eelgrass shoot,” Dr. Katharyn Boyer, a professor of marine biology at San Francisco State, told us. “It’s really good food for fish and some birds, and it’s a nursery habitat for juvenile fish. The roots of the plants help to secure sediments, so it’s good at reducing erosion, and is included in living-shoreline restoration projects. Locally, eelgrass can increase the pH of the water, which is good for organisms that form shells. This supports native oyster populations. Eelgrass is also good at storing carbon.”

Scientists have been studying mooring scars in Richardson Bay that no longer have a boat moored in them. “We have started doing some restoration planting in five scars so far in an experimental way, and trying to determine if it is valuable to plant, or if that area will recover on its own,” Boyer said.

The data do seem to suggest that eelgrass beds have grown over the last five years. “Between 2014 and 2019, there’s quite a bit more eelgrass than there was before, but there are still several damaged areas,” Boyer said, stressing that it’s not clear if the growth in the eelgrass population represents a trend, or rather, interannual variations that are tied to fluctuations in rainfall. Eelgrass expands during droughts, and recedes in high-rainfall years.

“We have some bigger concerns than eelgrass, such as taking care of the numerous Superfund sites around the Bay Area,” a former Richardson Bay anchor-out told us in 2018. “Eelgrass is a straw man’s argument — it’s just one of the many excuses to justify dealing with a portion of the population that is undesirable.” (The Marinship — Sausalito’s working waterfront, which is home to hundreds of businesses, several restaurants and many liveaboards — is categorized as a “Non-Priority Superfund Site.”)

Both Boyer and the firm contracted to do the feasibility report acknowledged the importance of finding a balance between the environment and people’s lives. “We are very conscious of the fact that there is conflict, and we’re not advocating for harm to anyone that could result in them losing their home,” Boyer said. “I don’t think anyone out there means to harm the eelgrass. I’m for minimizing the impacts; getting boats out of the eelgrass doesn’t mean that there can’t be moorings anywhere.”

If you’re anchored on Richardson Bay, then you can expect at least one solid storm a year — if not a handful. Boats, their tackle and their owners will be tested, though in many cases, boats are unattended during weather events.

In January 2021, a Norther caused five boats to drag into Schoonmaker Point Marina in Sausalito. An unoccupied 25-ish-ft sailboat dragged into the 40-foot wooden cabin cruiser Salty, which was anchored out. Salty smashed against a dock, broke up, and sank. The owner escaped with a few possessions, but her dog was lost. A Marin waterfront homeowner recently told VICE News that boats that had broken anchor had crashed into the dock or deck of his house “a minimum of 16 times. And that’s not uncommon up and down the street. It happens all the time.”

Several marina operators have told us that, at times, some anchor-outs have used their facilities as if they were public, and that some people were less-than-stellar stewards or neighbors. An East Bay harbormaster told us that, last year, someone dumped a portable toilet into a landscaping planter in the marina. Even objects as seemingly innocuous as garbage dumpsters have become points of contention — one Richardson Bay harbormaster said that that it could cost the marina thousands of dollars a week for the increased trash pickup.

Some longtime liveaboards in Sausalito have told us that these kinds of problems are just the tip of the iceberg. It’s here, at the end of this story and at the end of this era, that we again run the risk of making sweeping generalizations about people. But we also run the risk of not calling out bad behavior and bad seamanship for what it is.

In the end, the anchor-out debate is about a crisis bigger than boats moored on a bay, bigger than this publication, and bigger than the people and agencies who are forced to confront the issue. There is an affordable-housing crisis in the Bay Area, and it can manifest as homelessness, which can lead to mental health issues or drug abuse. It has manifested on the water, and in encampments around marinas in the East Bay. This is not something that the BCDC, RBRA, harbormasters or the police can solve — nor should they be asked to.

We hope for peace, safety, a clean environment, and with luck, just a few well-found, well-maintained boats anchored out on the Bay.

Please click here for Part 1 of this series, and here for Part 2.

First, thank you Latitude 38 for publishing this series of articles. Problems resulting from anchor-outs have existed since before I sailed around here, and are a serious issue for the water and marine life here, as well as the rest of us.

Curtis Havel’s comment pointing out that pollution from anchor-outs is a minor part of the pollution in Richardson Bay or anywhere else is a form of propaganda called “whataboutism.” This is like a child responding to being caught doing something wrong by saying, “well, she did it too!” The fact that there are larger polluters than anchor-outs doesn’t mean that we should just ignore the latter’s pollution, quite the contrary. Of course the most resources should be focused on stopping the biggest problems, but this is a sailing magazine, not an Earth First! journal. Runoff pollution is caused by living industrially, and that problem is well beyond the scope of Latitude 38. If someone’s behavior is causing an environmental problem, that behavior needs to be stopped, regardless of whether someone else is also contributing to that problem and regardless of who is doing the most harm.

Same for the eelgrass destruction problem. As a lifelong environmentalist, I can vouch for the fact the habitat destruction is a fundamental environmental and ecological problem. If you want to save species, you must save their habitat, period. Saying that “[e]elgrass is a straw man’s argument” as an anchor-out falsely claimed is just showing that you care only about yourself and not about the environment. Any destruction or unnatural human harm to a natural habitat is a serious problem. Claiming that wanting to protect and restore the natural habitat is just an excuse “to justify dealing with a portion of the population that is undesirable” is the real straw man argument here. While there are surely some people who oppose anchor-outs because the former consider them undesirable, those of us who raise environmental concerns do so for that reason.

One of the fundamental problems with liveaboard anchor-outs is that properly maintaining a boat takes time, effort, and money. If the boat isn’t maintained properly, among other things it can pollute the water and even sink. People anchoring out and living on their boats because they can’t afford to buy or rent a home on land clearly don’t have the money to maintain a boat properly. And as harbormaster Bill Price diplomatically put it, many people living on anchor-outs are landlubbers who know nothing about sailing or maintaining a boat.

What this all boils down to is whether we’re going to prioritize the natural environment or social issues. If you want to fight for the least among us, you fight for the natural world, where entire species are becoming extinct because of humans, and where entire habitats and even ecosystems are being destroyed. Humans as a whole, on the other hand, are thriving and expanding. Additionally, for strictly practical reasons, we must protect the natural environment, because we can’t live without it. While I find it unconscionable that there are homeless people in the richest country in the history of civilization and while I advocate for spending whatever it takes to get people homes, I always put the environment first, as I do here.

Perhaps conservation moorings can stop and reverse some of the damage to eelgrass, let’s hope so. Again, I have no opposition to anyone anchoring out or living on their boat — I lived on boats for months the voyage from Tahiti and back. My problem is people polluting the water, harming ecosystems, and causing navigation hazards. If anchor-outs don’t do any of those things, I see no legitimate reason to prevent or harass them.

Jeff — Thanks for your comment, and for reading this series.

Although there is no evidence showing widespread pollution coming from anchor-outs, we regularly hear readers assert that human waste has sullied water quality. This talking point has caused an already bitter divide between communities to widen, and is a distraction from what you mentioned is the real issue: that boats are not suitable housing alternatives for people living on the financial margins.

You said, “The fact that there are larger polluters than anchor-outs doesn’t mean that we should just ignore the latter’s pollution.” We agree Jeff, but what pollution are you referring to? Official sources have said that water quality in Richardson Bay is good (despite even the semi-regular spills from municipalities). We all seem to assume that anchor-outs must be throwing something over the side, and it’s not an unreasonable assumption, since many anchored-out boats are old, and since most sailors — regardless of income status — probably pee over the side at least a few times during a sail, beer can race, etc.

(In April 2020, we were anchored-out in a Southern Hemisphere-country known for its fierce protection of its pristine ecosystem. [Just a few weeks prior, two government divers popped up beside the boat after inspecting for invasive species on the bottom.] Because of the lockdown, we weren’t able to sail the required three miles offshore to dump the composting toilet, so the captain made the decision to pour nearly five gallons of composted poop in the harbor, at night, on an ebb tide. We were shocked, but she quoted a well-known, widely read sailing couple, who had written that composted human waste was completely inert. We even swam off the boat a few days later.)

As for eelgrass and larger environmental concerns, we agree that sailors should do everything they can to make as small an impact as possible. We again call on the municipalities around Richardson Bay to install the most state-of- the-art moorings on the market, so that weekenders and transient cruisers can also minimize their impact. (Eelgrass grows in water up to about five feet, so the assumption is that larger, deeper-draft vessels don’t pose the same risk to beds as smaller boats do.)

But in the end, pollution and eelgrass are kind of beside the point, aren’t they? (Are they a ‘strawman argument’? You be the judge.) We believe these are well-intentioned concerns that ultimately distract from the core issue: There is an affordable housing crisis in the Bay Area, and an increasing number of people who are unhoused, or on the verge of losing their housing. This has led many people to live in boats that are often free, but are old and in poor repair. Poor plumbing and environmental impacts are small symptoms of a larger issue, and we think it’s best to deal with the people and their situations as directly and honestly as possible.

@Tim Henry

We basically agree. We should not be in this situation to begin with, because people should have affordable housing. However, environmental concerns are NEVER “beside the point.” They are always the primary point. Humans aren’t the only ones living here by a long shot, and we need to stop acting and living like we are.

To be clear, I don’t know for a fact that anchor-outs are dumping their sewage into Richardson Bay or anywhere else, but it only makes sense that they’re doing so. These people have no dock privileges, so unless someone offers to come to their boat and pump out their sewage, where else would it go? As to the eelgrass issue, I just want it all protected by whatever means necessary. Perhaps the vulnerable areas should be cordoned off to prevent damage? I am far from being an expert on any of these issues, so it’s possible that I’ve been led to believe that these are serious environmental problems when in fact they’re not. But that said, anyone other than a marine biologist is not qualified to say that these activities don’t cause serious environmental problems, and I’m definitely not going to take the words of anchor-outs, who are both unqualified and biased regarding these issues.

One of the problems with getting people to realize how much environmental damage certain human activities cause is that there are almost 8 billion of us on the planet, but people individualize the activities when thinking of the harms they do or don’t cause.. One boat dumping a little sewage or killing a little eelgrass once in a while doesn’t seem like a big deal, but multiply that by 8 billion, then rethink it. (After all, if one person may do it, everyone should be allowed to do it.) To reiterate my position, I have nothing against anchor-outs if they don’t harm the environment or cause navigation hazards. Making them move or harassing them for the sole reason that some people think that they’re undesirable is disgusting, and I totally oppose that.

A thoroughly informative three-part series — much appreciated! If Richardson Bay does end up with a mooring field, I hope that 5 or even 10 moorings can be designated for use by transient cruisers and recreational boaters visiting different parts of the Bay. Every boat using a mooring — a public facility, after all — should be registered, insured and subject to the same random Coast Guard boardings for inspection of compliance, safety and operability as everyone else is. Presumably that would require some kind of administration —- perhaps that is why San Diego’s Harbor Patrol clears in all visiting boats?