Mixed Fortunes in the Transpac

The Unfortunate Fate of One Boat

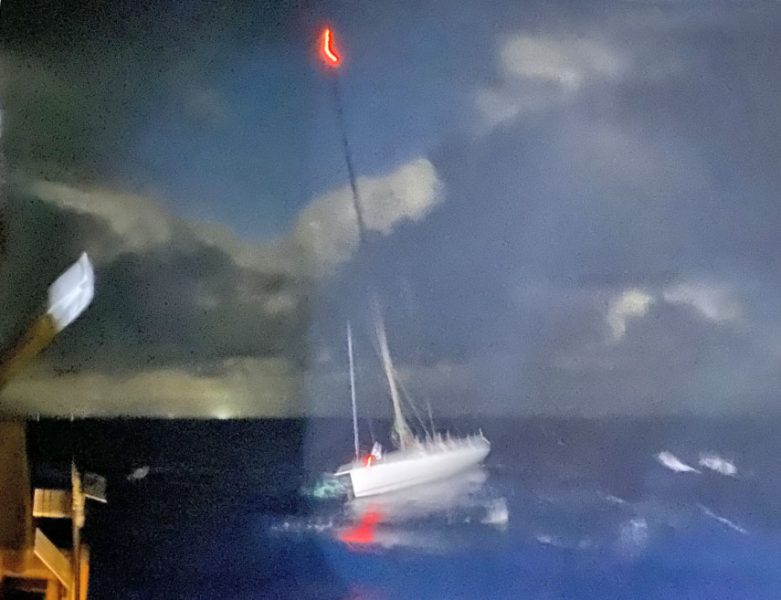

Most of the competitors in the 51st Transpac Race from Los Angeles to Honolulu have finished, but one boat was not so lucky. Ironically, that’s the name of the boat — Lucky. According to the US Coast Guard District 14 report, USCG crews took the 72-ft yacht, with 15 sailors aboard, in tow just 26 miles east of Makapu’u Point, Oahu, on Saturday. “The Lucky was adrift due to a disabled rudder. Crews aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Oliver Berry (WPC 1124) and a Station Honolulu 45-ft Response Boat-Medium successfully towed the vessel to Honolulu Harbor.”

“In 30-knot winds and 10-ft seas we were able to establish a tow with the Lucky and safely brought them back to Honolulu,” said Ensign Michael Meisenger, the operations officer aboard the Oliver Berry.

Lucky’s multinational crew notified Sector Honolulu watchstanders of their situation at 1:32 p.m. on Friday. The rudder had became disabled, and the Judel-Vrolijk 72 was drifting toward Oahu. The sailors aboard had no medical concerns. “After reviewing the situation and determining the mariners were not in immediate danger, watchstanders diverted the crew of the Oliver Berry to conduct a tow operation at 6:45 p.m.,” reported the Coast Guard. “The Oliver Berry and Lucky arrived outside Honolulu at 2:30 a.m., Saturday, and the tow was transferred to the RB-M crew.”

While it’s an extremely lucky boat that makes it from California to Hawaii without some gear failure, it’s fairly unusual for damage to be dire enough to require Coast Guard assistance.

Meanwhile, in the Rest of the Transpac Fleet…

“We’ve had 90% of the fleet finishing in two days, so it’s been manic here,” noted Transpac’s media contact, Dobbs Davis. We can only imagine! As reported in Friday’s ‘Lectronic Latitude, Pyewacket 70 and Ho’okolohe finished on Friday morning. Other than those two, all of the boats arrived between Saturday and Monday morning.

Because of COVID-19, the trophies are being awarded in stages. Yesterday, in the first of three daily sessions, the top three places in Divisions 1 and 2 were awarded, with Tom Holthus’s Botin 56 Bad Pak winning Division 1 and Doug Baker’s Kernan 68 Peligroso winning Division 2. The first-to-finish monohull Barn Door Trophy was also presented to Roy Disney and his team on Pyewacket.

Holthus’s previous Bad Pak, now Chris Sheehan’s Warrior Won, is projected to be the overall champion in this year’s race.

Fathers and Sons

Dads and sons sailing together has been a theme of this year’s race, as Dobbs Davis reported in his missive to the media last night. Kelly Holthus, 16, sailed aboard Bad Pak with his dad Tom. This was Kelly’s third Transpac since first racing on his dad’s Pac52 of the same name four years ago, and serving — at age 12 — on a class-winning team.

Many other father-son pairs sailed the Transpac this year. John Sangmeister’s twin sons Jack and Peter sailed with him on their Andrews 68 Rock ‘n Roll (ex-Mr. Bill) that John co-skippered with Justin Smart. Michael Dahl, a 20-something, sailed with his brother Sean and his dad David, a partner in the Andrews 77 Compadres team from Newport Beach; Bart and Brett Scott also sailed on Compadres. Jay and Joe Crum raced on Raymond Paul’s Bay Area-based Botin 65 Artemis, and Artemis boat captain Carlos Badell sailed with his son Delmar, who does the bow. We’re not talking about a little kid managing the foredeck. “Delmar is 50 this year,” said Carlos. “I got started early.”

See the complete results here and much more info at https://transpacyc.com. We’ll have complete coverage in the September issue of Latitude 38. (The August issue has already gone to press, and will be distributed this Friday.)

Aussie Rower Launches Second Attempt at Ocean Crossing

At the end of May we brought you the story of Aussie rower Jason Harrison, who was departing San Francisco Bay on a 200-plus-day voyage across the Pacific to his homeland, Australia. Jason was attempting to break the record set by ocean rower John Beeden, who made the journey in 208 days. Unfortunately Jason’s record bid has been defeated this time. The rower encountered problems with his rudder and autohelm when he was only three days into his voyage. It seemed the Pacific weather was determined not to let paddle-craft cross this season, as Jason was caught in weather conditions similar to those that caused ocean kayaker Cyril Derreumaux to initiate a USCG rescue on June 5.

“I spent five days and five nights in the storm,” Jason told us last week from Monterey. By this time he was 100 miles offshore and had to make his way back to land. “I used an emergency sail to get part of the way, but then I had to row three to four days back up the coast to get to Monterey.” To add to his dilemma, Jason’s tracker hadn’t been functioning, which accounts for the large blank on his Garmin page. “I’ve always been a bit of a loner anyway,” he laughed.

Although he didn’t feel he was in any immediate danger, Jason advised the Coast Guard of his situation. “They flew overhead at some point. I imagine they were looking out for me.”

After spending a month in Monterey conducting repairs, restocking, and reevaluating his journey, Jason is planning to set out again this week. “I was never in for the record this year,” he conceded. “Hawaii is manageable, but if the weather pushes me south I might end up in Mexico.” That said, the adventurer’s 8.5-meter rowboat carries enough supplies for 240 days.” By comparison, John Beeden rowed a 6.5-meter craft on his Pacific crossing. Beeden ran out of food before reaching Australia and had to restock in Vanuatu, which meant he was unable to include “unassisted” in his record claim.

Jason Harrison’s Facebook page “2021 USA to AUS Pacific Ocean Solo Row” describes his journey as “Rowing Solo in an 8.5-meter Ocean Row Boat unassisted from San Francisco, USA, to Cairns, Australia” — the same start and finish point as Beeden. And although he intends to row unassisted, Jason acknowledged that to even attempt his voyage, he’s had an abundance of help and support from Bay Area businesses and locals.

Right from the start Jason’s voyage was delayed for six weeks while he waited for the freight company to deliver his boat. “The motel costs were three times the amount of mooring fees, then tried to depart two days later but was unable to leave because of my desalination machine hose fitting, and other issues due to time and weather,” he wrote on his Facebook page. But in true sailor style, it was the community that helped bring Jason’s dream to fruition.

“The hospitality, the kindness and generosity!” he exclaimed. “Chris and the crew at Grand Marina in Alameda were absolutely awesome. Bill at Spaulding Marine Center helped me with my watermaker. He came all the way over to Alameda to fix it, and didn’t charge me a thing! And Galen at SeaTrek, and my Sausalito dock neighbors Tim and Olga who fed me and and looked after me. The community is just awesome.’

While Beeden set out on his voyage with the sole purpose of setting a new record, Jason is approaching his voyage from a slightly different angle. The record is still a goal, but with a broader purpose.

“It’s how you push the direction of the adventure — the environment, politics, plastics. All the things humans face in society,” he told us. “I want to raise awareness, educate and grow young, developing minds in areas that would improve the life of all Australians and people from around the world.”

When we spoke with Jason on Friday, he was planning to set off today, but due to a forecast of strong winds, he’s pushed his departure back to Wednesday. We’ll aim to bring you an update later this week. In the meantime, you can check out Jason’s adventure on his Facebook page. And if you’d like to become part of the “awesome sailing community” that’s supported him so far, you can contribute on his GoFundMe page.

KKMI Is Hiring

Volunteers and Crew Celebrate Progress at Spaulding

Last Friday saw the completion of Spaulding Marine Center’s 2021 summer camp season. And with the upcoming launch of the nonprofit’s Boatworks 101 apprenticeship program, the team thought it was a good opportunity to get volunteers and crew together to celebrate the success of the camp, progress on the Pelican fleet, and their upcoming marine technician program.

“It’s been a fun couple of months,” said Jay Grant, Spaulding’s education director. “The kids were able to learn about sailing in the Pelicans, build their own model boats, and in between just have some fun. Our camp counselors Danny McKay and Justin Mayer were fantastic, and the kids had a really good time, judging by the feedback and cards we’ve received from their parents.”

And while the young ones were sailing and building model boats, a team of enthusiastic volunteers were working alongside the Spaulding crew to build six new Pelicans, which will make up the organization’s fleet of community-sailing boats.

“The volunteers, and our crew, everyone’s been great,” Jay told us. “So we wanted to thank them.

“We’d like to get everyone together on a regular basis,” he added. “They’re a big help!”

Meanwhile, on the adult education side, Boatworks 101 is only a few weeks away from its inaugural program.

“We’ve had a lot of good response from the industry,” the education director said. “A lot of businesses and companies have jumped on board and will be supporting us with learning materials and training equipment, as well as their experience and expertise.”

“We’re pretty excited about it,” he added.

Closing the Deal

In the July issue of Latitude 38, Kristian Beadle shared the story of his family’s stressful time closing the deal on a new boat purchase …

We had 7-month-old babies strapped onto our bodies when the catamaran’s seller lost his marbles, and nastily told us to get off his boat.

I felt a sudden, slow-motion desperation. I was a new father of twins, and like an overconfident poker player, I had “put all my chips in” — and was about to lose it all.

In mid-pandemic (August 2020), my wife Sabrina had shipped all our belongings by cargo to the atoll of Rangiroa, in French Polynesia, where we planned to move aboard a 46-ft Fountaine Pajot cat whose owner had signed a contract the previous year.

The trip to the boat had to be delayed when our twin girls, Kaiana and Naiyah, were born prematurely (29 weeks) in January 2020. So those first months of life were a marathon battle, including three months living in the hospital’s neonatal ICU in the San Francisco area.

In July, the pediatrician gave us the green light. A month later, we flew with 26 bags from San Francisco to Papeete, along with our friend Alexandra to help us as nanny during this chaotic transition.

By the time we arrived in Rangiroa, we were completely fried, yet we agreed to meet the seller at the boat the next day. The meeting went … very poorly.

“You’ve pushed it too far!” he yelled as he fired up the dinghy, in essence kicking us off the boat. “You don’t trust me! That’s it!” He was incredibly angry. He expected me to evaluate the boat in the span of a few hours. And I had the temerity to ask for what was spelled out in our contract.

Pandemic stress ignited his outrage. Later I learned that his wife and son were pressuring him not to sell the boat. Their other plans fell apart due to COVID, and suddenly, the boat’s importance magnified: It was their home and business, and one reliable foundation in life.

The family had lived aboard this boat for 11 years, running classy charters as their income, enjoying a good life. They had decided to move off to give their son a good education. But why should they now plunge into the uncertainty of terrestrial existence at the worst of times?

Our $20,000 down payment in the seller’s account was only secured by a measly contract — no broker, no escrow account (I know, I know … I’ve learned my lesson). Handshake integrity was the binding force.

Continue reading at Latitude38.com.