California Proposes 250% Increase in Boat Registration Fees

The State of California has suggested a 250% increase in vessel registration fees in its 2021-22 budget. This would represent an increase in fees from $20 every other year to $70, and would take effect on July 1. The fee hike is currently under debate in Sacramento, and a state boating advocacy group is asking that lawmakers take a more incremental approach to raising fees, which haven’t seen an increase since 2005.

The proposed fee hike is meant to bolster the Harbors and Watercraft Revolving Fund, or HWRF, which supports several programs and services “that benefit boaters including infrastructure such as launch ramps, education, aquatic centers, local boating law enforcement, the boater certification card, and invasive species prevention and control,” according to the Recreational Boaters of California, or RBOC, a nonprofit advocating for boating interests.

The HWRF is not part of California’s general fund, so it has to raise money via registration fees, as well as boat fuel tax dollars and federal monies. The fund is looking at a $52 million annual deficit, according to The Log, which added that the proposed 250% hike would increase vessel registration revenues by $22 million annually.

“If you need to increase fees, let’s do something reasonable,” said Winston Bumpus, the RBOC president. “We’re trying to put the brakes on.”

Going down a bureaucratic rabbit hole for a moment (and adding more abbreviations), the HWRF is administered by the California Department of Boating and Waterways, or DBW, which was absorbed by the California Department of Parks and Recreation in the recent past. It seems clear that the parks department has dipped into the HWRF for non-boating-related expenses.

The Log quoted an email they’d received from DBW staff: “The [HWRF] has faced increasing cost pressures — such as climate-driven expansion of the Aquatic Invasive Plant Control Program (AIPCP), new fund commitments for the Public Beach Restoration Fund, and increasing employee compensation costs — without additional revenue sources.” The Log went on to quote a DBW official who said, “We will not have sufficient resources to continue at current service levels.”

Bumpus said that “boaters pay $107 million in fuel tax, but only $15 million goes back into DBW. They’ll get an extra $20 million out of boaters, particularly during a time when boating is on the increase,” he added, referring to the pandemic boating boom, where manufacturing, sales — and presumably registration coffers — are burgeoning. Bumpus also said that in addition to the fuel tax, boaters pay a significant amount of sales tax.

The RBOC is encouraging boaters to “Make their Voice Heard.”

And Now for Some History on the Columbia 5.5

In this month’s Latitude 38 we share a story about the Columbia 5.5. The story prompted Candy from Alameda to send us this:

“I loved the article on the Columbia 5.5 Meter. My late husband and I had hull #4 for years at Stockton Sailing Club and I have great memories of all the weekend racing we did. After we sold Feather, as she was known then, she changed hands/names several times. The picture of the red 5.5 [in the March feature] looks a lot like her. The 5.5s are fun boats to sail and absolutely gorgeous. If any readers happen to visit the SSC, as far as I know the class trophy is still a stainless steel bedpan.” – Candy, s/v Infidel, Alameda

Read the story to find out more about the 5.5 and the “stainless steel bedpan.”

I remember the first time I laid my eyes on a Columbia 5.5. A friend had called me over to see his new toy at Alameda Marina. Unfortunately for my friend and his Ericson yacht, there was a beautiful, Corvette-red sloop resting in the slip opposite, her bow rising from the water with the elegant arc of a calligraphic stroke. From the fresh gloss of her flush deck and teardrop-shaped hull, I could see that she was adored. “What a beautiful … Folkboat!” I exclaimed, enthralled, admiring and not entirely sure what I was looking at. While my mistake didn’t come to light until much later, what was obvious then was my friend’s irritation as I hovered, cooed and pointed. Yes, the debut of his burly daysailer had been completely upstaged, and by nothing less than a skinny, 32.5-ft Nordic supermodel of a boat.

This is the moment I found a desire to learn more about the Columbia 5.5 — not to mention, the origins of this one-design keelboat class. When Columbia Yachts of Costa Mesa introduced the Columbia 5.5 Meter back in 1963, it was to democratize access to the International 5.5 Meter Class. At the time, the International 5.5 Meter was an Olympic class, whose boats’ custom wood construction placed them at a price point well out of reach of most competitive sailors. By mass-producing the boats using a then-new material called “fiberglass,” Columbia Yachts had an opportunity to bring to market not just a more affordable 5.5 Meter boat, but one that was considerably lighter than its contemporaries.

To stay true to the design, Columbia bought a successful 5.5 Meter, Carina, from Alexander (Sasha) Von Wetter. Carina was built by Sigurd Herburn in Norway for the 1956 Olympics; her claim to fame was winning the 1958 Scandinavian Games Gold Cup. In the years that followed, she changed hands, and had remarkably made her way to the West Coast, where, by Sasha’s account, “The only organized racing I could do was PHRF, and that was not what a one-design racer like myself, or a thoroughbred like Carina, was particularly adept at.”

Columbia Yachts approached Von Wetter in regards to striking a mold for their own one-design boat, albeit with modifications made in resemblance to George O’Day’s 5.5 Meter Minotaur. O’Day and Minotaur had won both a world championship and a gold medal at the 1960 Olympic Games. Columbia had initially wanted to buy this design, but according to Von Wetter, the builder and the former Olympian could not come to terms.

According to a 1966 Columbia brochure, the boats produced from this hybrid mold were “the most sophisticated racing yachts in this country, at less than one-half of what an ‘Open 5.5’ would cost.” Unfortunately, the International 5.5 Meter Class banned these lighter designs (at least initially), thus extinguishing the interest from potential buyers wishing to engage in class racing. In all, fewer than 50 hulls were produced. A spin-off design, the Saber — essentially, the same hull with a raised deck, cabin and bunks for four installed — was more prolific; between 300 and 400 were built from 1963 to 1969. But until fairly recently, the 5.5 design was all but mothballed by Columbia Yachts.

Please continue reading at Latitude38.com.

EWOL Propellers — Setting the Pitch

For more information visit Ewol Propellers.

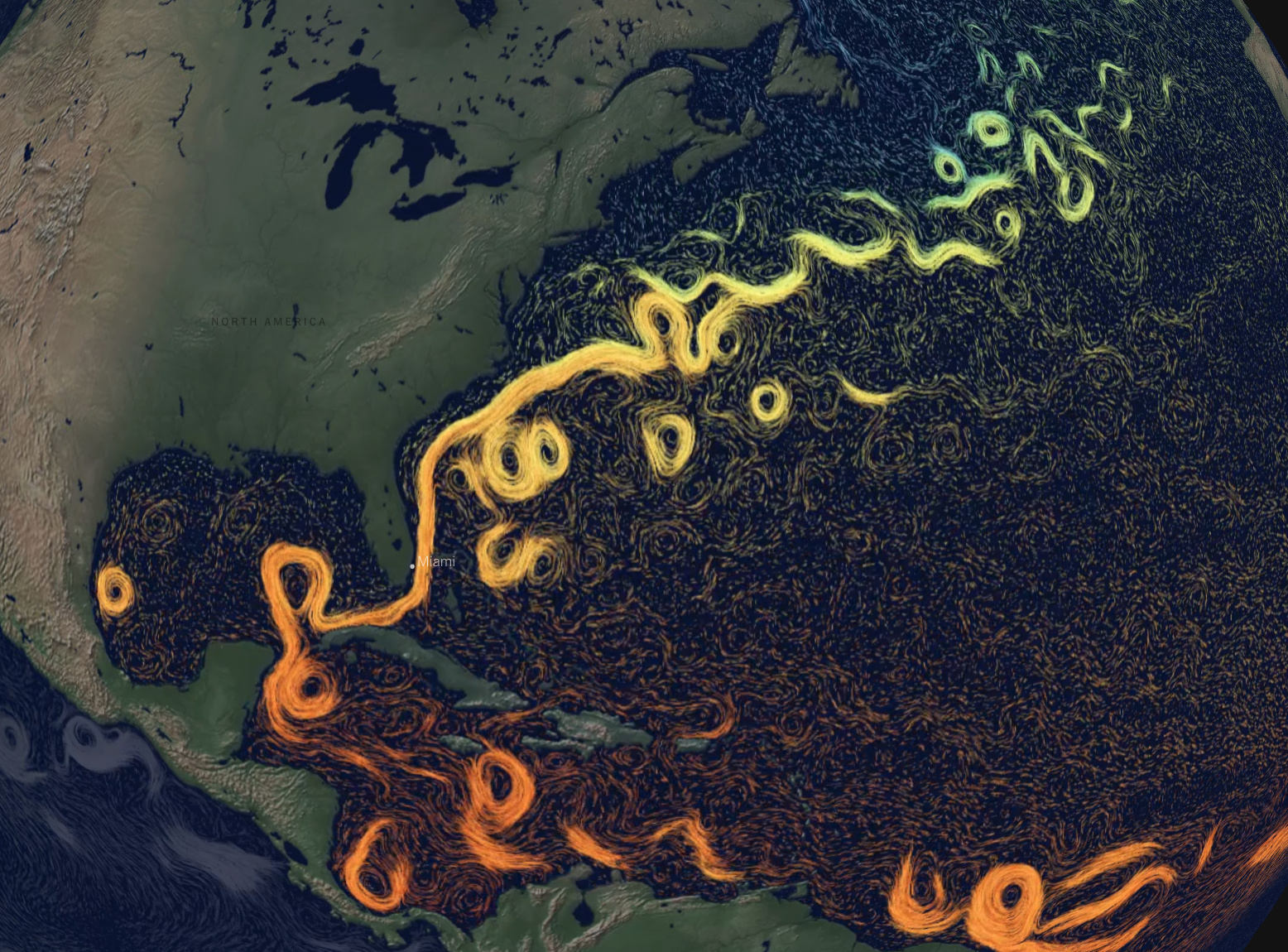

The Changing Course of the Gulf Stream

Sailors know that sailing in San Francisco Bay is hugely impacted by the current. On a larger scale, the Gulf Stream is the most important current affecting racers crossing the Atlantic or to Bermuda, but more importantly, it is the major reason palm trees grow at 50 degrees north in England and not at 40 degrees north in New York. A fascinating article in today’s New York Times reviews the latest science on the changing nature of the Gulf Stream and how those changes may impact the climate in Europe and Africa, and almost around the entire globe.

While the Gulf Stream current has ebbed and flowed over the eons, climate scientists are concerned that the accelerating rate of climate change could slow the Gulf Stream, creating a tipping point in our rapidly changing ecosystem. According to the article, Benjamin Franklin was the first to map the Gulf Stream during a transatlantic crossing in the 1700s (who thinks of him as a sailor?), and understanding its path has been a key factor in every Atlantic sailor’s course ever since. The future is forever uncertain but it’s always wise for sailors to pay close attention to forecasts. You can read more about Benjamin Franklin’s chart here.

The Female Factor in the Vendée Globe

Clarisse Crémer First Woman to Finish

French sailor Clarisse Crémer, 31, on Banque Populaire X, finished the Vendée Globe solo round-the-world race on February 3, placing 12th out of 33 starters. In the final days of her race, she cautiously battled stormy seas and 30-knot winds in the boisterous Bay of Biscay before reaching the finish at Les Sables-d’Olonne.

Her elapsed time of 87 days, 2 hours, 24 minutes breaks Ellen MacArthur’s 21-year monohull solo nonstop record for a female skipper of 94 days, 4 hours. MacArthur set the record when she took second in the 2000-2001 Vendée Globe. Dame Ellen sent Crémer her congratulations: “Just a little message to say a big bravo for your race around the world. It’s great to see you at the finish line. It’s truly an exceptional lap. Well done for everything you have done!”

Pip Hare First Briton

Pip Hare, 47, finished in 19th place, the first Brit in a mostly French fleet. Her 21-year-old IMOCA 60, Medallia, is the oldest boat in the fleet. Hare emerged from the bitterly cold Bay of Biscay in the midnight hour of February 12. She’s only the eighth female ever to finish the Vendée Globe in its history. Her performance is all the more remarkable considering that her first IMOCA class race — the Rolex Fastnet Race — was in August 2019.

She’s one tough cookie. She lost one of her hydro-generators on November 29. That meant saving all her diesel for power generation, sparing none to heat her cabin. She had to ride out the discomfort of being wet, cold and damp in the Southern Ocean. On January 2, her wind sensor failed. The cups stopped rotating, and the boat crash-jibed as the autopilot stopped receiving information. The AP would no longer steer in wind mode, and she had no accurate wind information. From then on, she was on a high state of alert, and the sharpness of her attack was dulled.

On January 7, some 1,000 miles to Cape Horn, she discovered a crack in her port rudder stock. Fortunately, she was carrying a new spare rudder, and she had practiced installing it. Replacing the rudder in big seas and 25 knots of wind allowed her to stay in the race and keep close to a group of four fast rivals. In the South Atlantic she slowed down in order to laminate a repair to reseal the rudder tube, which was letting in significant amounts of water.

Hare’s sponsor, Medallia, is “a customer and employee experience management company” based in San Francisco. We’ll have more about Pip Hare in an upcoming issue of Latitude 38.

Melinda Merron and Alexia Barrier

Two more women then finished the race. Brit Melinda Merron, 51, arrived on February 17. Merron had tens of thousands of ocean miles under her keel going into this race. Her sailing career started in 1998 when she was part of Tracy Edwards’ crew vying for the Trophée Jules Verne record — alongside a young Sam Davies. In 1999 Merron won the 50-ft class of the Transat Jacques Vabre with Emma Richards. French skipper Alexia Barrier, 41, completed the Vendée Globe loop at dawn on February 28.

Samantha Davies and Isabelle Joschke

During the night of December 2, British skipper Sam Davies, 46, sustained a violent collision with a floating object south of Cape Town. She abandoned her race, which had been going so well. She had been sailing at 20+ knots when her IMOCA 60 Initiatives Coeur stopped instantly. The sudden impact threw her across the interior of her boat, injuring her ribs.

Three days later, she pledged to return to sea and complete her solo voyage. “In my head the race was dead. I had stopped sailing, I had retired, I already could picture myself at home wearing my little dress ready to pick up our 9-year-old son, Ruben, from school and being back to making food at home,” she told the media in South Africa. “Instead of that, I changed my mind. I came to my senses.”

Her technical team, supported by local Cape Town ocean racers and boat builders, worked tirelessly around the clock to effect the necessary repairs. Davies was back on the water on December 14.

Off the Brazilian coast, Davies reconnected with her longtime friend and rival Isabelle Joschke. The Franco-German skipper had had to abandon due to keel ram failures, but, like Davies was finishing the course unofficially. Joschke had struggled for 16 days to bring her boat to safety into Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, where she met with her technical team to make the repairs that allowed her to put to sea again and complete her first circumnavigation. Davies and Joschke stayed in close and regular contact for the rest of their passage.

On February 11, in the northeasterly trade winds of the North Atlantic, Davies lost her forestay and her J2 headsail. She saved her rig but had to slow down. On February 26, she sailed back into sunny Les Sables-d’Olonne, fulfilling her pledge to complete the course. Thousands of well-wishers lined the quaysides to welcome her back and pay tribute to her solo round-the-world voyage.

By completing her circumnavigation Davies maintained huge public support for the Initiatives Coeur project. She raised over 1.2 million euros to fund more than 100 heart surgeries for children from Third World countries.

Only one boat is still racing, Ari Huusela’s Finland-flagged Stark, with about 275 miles to go as of this morning.