Redwood City High School Teacher James Bender, Teaching in Croatia

People say the three great reasons to be a teacher are June, July and August. Captain James Bender is a shop teacher in Redwood City who, for the past several years, has spent those three months continuing to teach, though in the islands of Croatia. There, he has restored traditional wooden craft, bridged the gulf between nations in the Balkans with boats, and run outdoor educational trips for the local youth. He sent us a short update of his summer life. He’ll be back in the fall to teach locally and continue volunteering with Peninsula Youth Sailing Foundation.

As I sat and looked out over the islands, I was thinking back to the years before. I was sure that this was the fifth year we have done the Kornati Adventure, but my friend Lovro Skracic, whose family works the land and has hosted us each year, said, “No, it is six years; I am sure of it.” I trust Lovro. Not only to remember how long we have done trips, but also with all things related to the islands. Together we have run to catch the sheep, gotten up before dawn on the hot summer days to go collect the sage and other herbs for oils his family produces, cast the nets to catch fish, and sailed the traditional boats Gajeta (GUY-et-a) and Leut (LAY-oot) between the narrow channels of the Kornati archipelago.

Yesterday we went to visit Jakov on the island of Piskera. We first met more than 10 years ago during the race to Palagruza, the most remote island in Croatia. He used to work for the lighthouse service; now he lives full-time in the Kornati islands. He has sheep, and makes olive oil and grappa, or rakija in Croatian. He now has a family and they support his dream of returning to the land that his family has had for more than 175 years. A day well spent with friends enjoying homemade delights, hearing about and seeing how working the land has transformed him and his family: This is the Kornati Adventure. A journey to the heart of what matters, connection to the land and sea, friends and family, to live in body and spirit with the natural environment around you to understand truly what it means to live in a remote archipelago without access to stores and shops.

Jakov’s phone rings — back to reality. His wife is coming from town with boxes of staples and treats for the kids. She has gotten a lift from Slobodan Skracic on his wooden boat named Crna Macka (SER-na MACH-ka), Black Cat. He helped years before, transporting the kids to Kravljacica. We get to meet again mid-channel while loading boxes. Now well into his 70s, Slobodan has lived on this island since before World War II and has many stories to tell. As we say goodbye, I am reminded that with each new generation some traditions are lost, but many are gained, and each turn of the tide carries new energy and effort of preservation and diligence that endures to keep the things that matter alive.

The trip to the islands has been a good respite from work on Vinka, our traditional boat that has been in the shop since before the pandemic. Last week we finished the engine installation. Now, with a bit of cabinetry and electrical work to go, we hope all will be well for the launch of the summer program, but things are tight. With each day that passes in the islands I am torn. I need to be here and there at the same time. The pressure from each side gains strength as it is only a few more days till the students arrive. We know that the time passes, and especially here in Croatia it is impossible to rush, to force, or push things along. It is then that mistakes are made, relationships burdened, and what gains are made are inevitably diminished with force that is exerted. For now we will continue to work with concentration and attention to detail knowing that what we do will be for the greater good, for kids to have fun with the boat and for the preservation of tradition for all who participate.

There is, however, a bit of nervous anticipation, as there is with all things when you push the limits. The third phase of restoration of Vinka started in 2020, just before the pandemic. We have worked hard over the past few years getting the boat in shape. Now I am in Kornati getting things set for the trip and they are putting finishing touches on the boat, and we should be done by Thursday or Friday. We hope to launch the boat Saturday, and the students come the following week. With each day that passes I feel the anticipation of a new phase for Vinka, for our program, and for the students who participate. They will now have a boat that they can use and learn seamanship, navigation, teamwork, communication and all the other skills it takes to sail a traditional lateen-rigged craft.

We did a podcast with Captain/Dr. James Bender in fall 2023.

Good Jibes #150: Tony English on Pacific Cup Memories and Volunteering

This week’s host, Chris Weaver, is joined by Tony English to chat tales from the Pacific Cup (Pac Cup) and teaching the next generation of sailors. Tony is a sailor, boat restorer, and even delivery driver for Latitude 38 sailing magazine!

Hear how to train for the wide range of Pacific Cup scenarios, how he managed to win or finish top-five in many races, how to problem-solve during a race, what he loves so much about volunteering in the sailing community, and how to keep sailing fun.

This episode covers everything from the Pac Cup to junior sailing programs. Here’s a small sample of what you will hear:

- How did Tony start sailing?

- What were the early days of GPS like?

- How did Tony start doing Pac Cup races?

- What did he do for work?

- How did he start working for Latitude 38?

- Where is his delivery route?

- How did he start volunteering teaching sailing?

- What’s an exciting sea story he can share?

Learn more about the Pacific Cup: https://www.pacificcup.org/.

Listen to the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and your other favorite podcast spots — follow and leave a 5-star review if you’re feeling the Good Jibes!

Visit Naos Yachts for Full Sales and Service

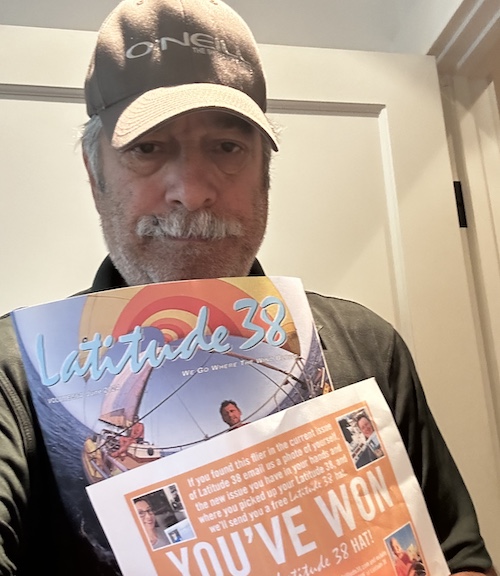

Winning Wednesday — Sailor Scores a New Hat

Latitude 38 reader Jack Swanson from San Rafael recently picked up the right magazine — Latitude 38 — and won himself a new hat! Jack grabbed his copy of the June issue at the West Marine store in Marin City.

“Sailing on the Bay and Delta for nearly 50 years has been a great experience,” Jack tells us.

Jack’s sailing life began with trips out of Buffalo on Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, along with summer camps in Algonquin Provincial Park, 230 miles north of Toronto, Canada. Prior to becoming a dad, Jack was a member of Corinthian Yacht Club. These days, rather than own a boat, Jack prefers OPBs and enjoys being a knowledgeable and helpful crew member whose favorite thing about sailing is “sailing with friends and meeting new ones.”

Whether we sail our own boat or crew for other skippers, we all have memorable sailing moments. Jack describes one of his most noteworthy sailing moments.

“While racing in an Express national regatta, we broached in the lee of Angel Island and we lost the mast. The skipper asked, ‘Is everyone OK? Well, I guess we’ll never be closer to the bar than we are now.’ We attached the outboard engine and sailed back to Richmond Yacht Club’s bar. The day was not a total loss.”

When asked if he has anything else to share, Jack replied, “Latitude 38 magazine continues to be an amazing publication. Keep up the great work. Thanks.”

Thank you, Jack; we appreciate your support!

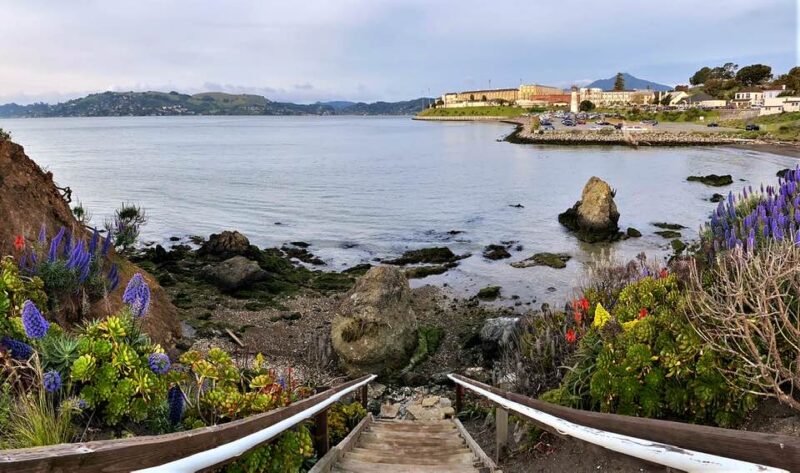

San Quentin: Prison and Paradise on the Bay Area Shoreline

Standing on the shores of Point San Quentin, I imagine Mount Tamalpais, silhouetted in the distance, as an erupting volcano with rivers of lava flowing through what is now Corte Madera Creek, where the ferry commutes up and down the channel. If sped up into a time lapse, you’d see ice ages come and go, mastodons, indigenous people, settlers, sailors, and scoundrels, many of whom would end up here — like me.

For nearly five years, I’ve been a resident of Point San Quentin, or San Quentin Village, a collection of houses tucked against the Richmond Bridge and the oldest prison in the state of California. Outside the gates and inside the Bay, it’s a busy intersection of ships, cars, bikes, ferries, windsurfers (like me), wingers, eFoilers, kayakers, rowers, dinghies and sailboats. In summer, gusty winds and shallow waters make for wild, confused seas; in winter it can be as glassy as a lake. San Quentin Village is both notorious and unknown, the kind of neighborhood you’d never know existed until you stumbled upon it. There are about 40 homes, a handful of condos, and 3,084 inmates inside San Quentin Penitentiary. After people give their predictably shocked looks when I tell them I live in San Quentin, they ask me if I’m affiliated with the prison, and if my house is inside the gates. (I’m not and it isn’t.) I’m just renting a reasonably priced room and working from home in a hidden-in-plain-site paradise perched against purgatory.

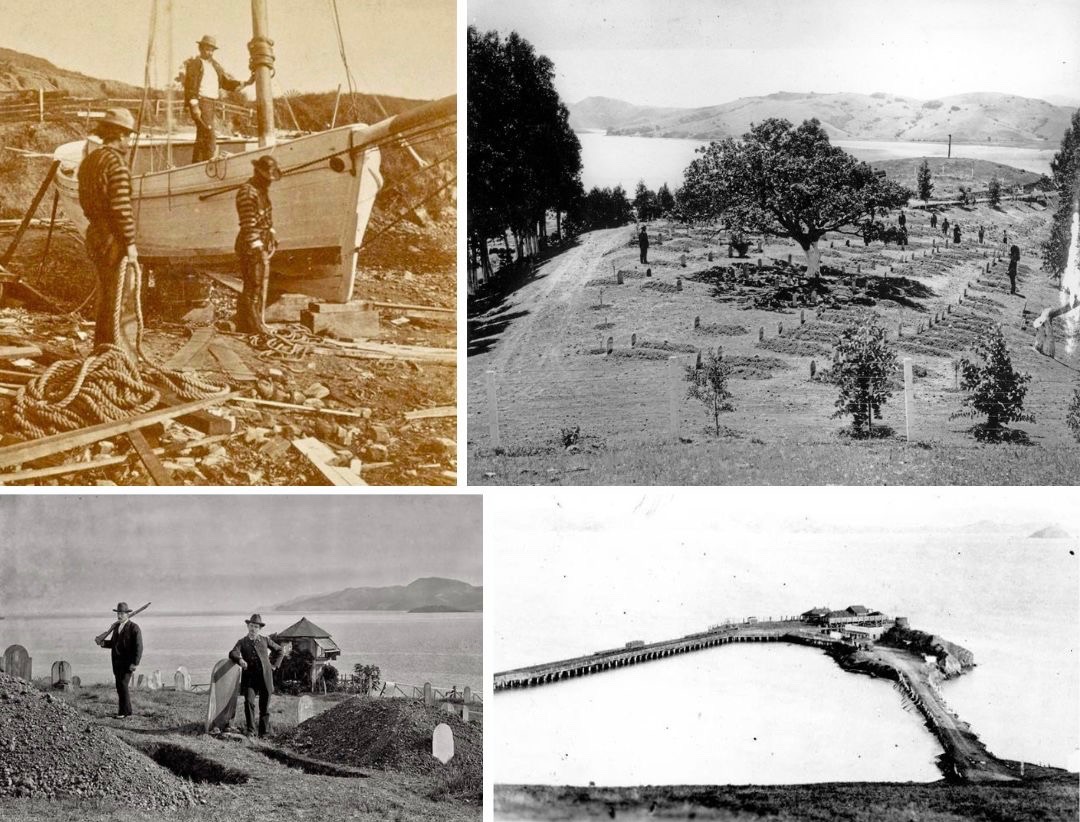

An Origin Story

Though California is defined by cities, towns and villages named after Roman Catholic saints, Point Quentin was actually named after the Coast Miwok warrior Quentín, who fought under Chief Marin — born as Huicmuse — while he was a prisoner at one of the iterations of the early penitentiary.

There were at least a few prison ships in the Bay Area in the mid-19th century, such as the brig Euphemia, which doubled as an insane asylum, according to San Francisco author Gary Kamiya. “Prisoners on the Euphemia anchored in San Francisco Bay and were sent ashore on a chain gang to do public works.” On July 14, 1852, the Waban, a 268-ton bark with some 40 convicts aboard, was towed across the Bay to Point Quentin. “Angel Island [the site of a quarry where prisoners worked], Alcatraz and Goat Island/Yerba Buena Island were the favored sites, but land-title problems led commissioners to choose Point Quentin,” Kamiya wrote. “The convicts were sent out during the day to work on the prison site, then locked up below decks at night. Four or five men were squeezed into each eight-foot-square compartment.”

San Quentin Village has seen numerous protests outside the gates of the penitentiary, including demonstrations against the death penalty, and objection to the state’s handling of a COVID outbreak in the prison. San Quentin is now morphing amidst a fundamental (and miraculously bipartisan) rethinking of the country’s criminal justice system. Governor Gavin Newsom’s administration has rebranded the prison as a rehabilitation center and is considering reducing the population, creating a vocational training campus, and building housing.

Latitude occasionally gets letters from prisoners in San Quentin and elsewhere. We’ve had requests for old issues, as well as general correspondence: Someone was teaching a navigation class at San Quentin; someone else sent us a small sketch of a crab-claw sail dinghy.

Sailing Chaos and Glory. But Mostly Chaos

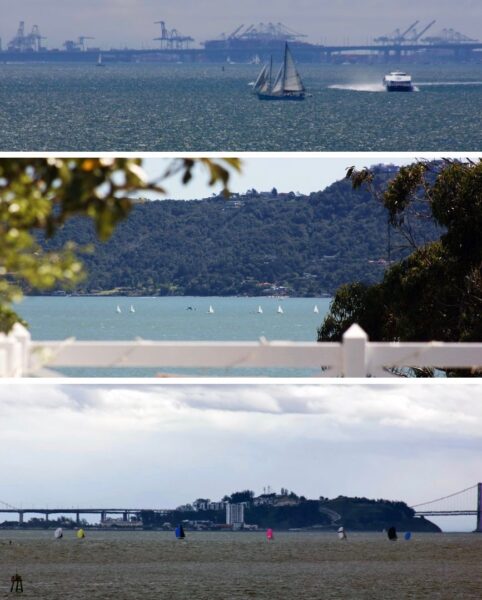

When I first windsurfed off San Quentin Beach in 2020 and sailed on port tack toward the parking lot and hulking fortress of the penitentiary, I wondered if the prisoners could see me. Do inmates appreciate the view (if they have one), or is it cruel and unusual punishment to watch boats and windsurfers come and go freely?

Being able to windsurf from my house (the beach is 74 feet from my driveway) was a dream I didn’t know I’d always had. On a northwesterly breeze, I can launch from the beach and “slog” through the lee of the prison, then hit the windline and sail perpendicularly to Corte Madera Channel, into the mud off Paradise, rather than the prevailing parallel direction to the prison. It was thrilling!

And then it was humbling.

In anything over 20 knots, and on starboard tack, outbound into the Bay, there’s the prevailing steep, short-interval wind swell from the west, as well as another swell coming from the east — a kind of “rebound” bouncing off the Richmond Bridge. It is total chaos, and finding a clean line is tricky. One day in 2020, I dramatically underestimated the wind on a traditional westerly day, and the sail would rip out of my hands when I tried to water start. I came back to the beach panting and a little spooked. The very next time I sailed off San Quentin Beach, I’d done a few runs and was in a good groove when my brand-new universal, which connects the sail to the board, snapped in two. I was more than a mile offshore and had to paddle back.

San Quentin went from dream scenario to kind of sketchy. It’s usually a mogul-filled double black diamond, the kind of run that you endure rather than enjoy.

San Quentin has become a winging mecca, which makes sense: Foils just float over the chop. I’ve never tried it, but I plan to, soon.

The San Quentin Surf Forecast

Going to San Quentin Beach feels like visiting an actual beach, even though it’s on the Bay. It is, apparently, one of the few beaches in the Bay that allows dogs, which has created some tension with locals. (Parking is a huge issue.) I’m a dog person, so I don’t really mind, but the beach is a kind of barometer indicating population pressure — and the pressure is rising.

On glassy days, I enjoy prone-paddling a nine-ft fiberglass windsurfer off the beach and around the prison, or across the channel to Paradise. One day a few years ago, I was on the west side of the prison, near Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, when a ferry was inbound to Larkspur. The captain gunned it as they went by me, kicking up what (I swear to God) seemed like a head-high wave. I missed the first one, but caught the second and rode it for … maybe five to seven seconds before it petered out into deep water.

I tried chasing ferries for months afterward — at least 10 times — and have only been in position for a breaking wave once.

But I missed it.

The View From the Crow’s Nest

If “there is nothing — absolutely nothing — half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats,” then simply watching boats come and go must be a quarter as much worth doing (if my math is right).

Sometimes, it feels like I have a giant model-boat set next to me. There are windsurfers and wingers off the beach, there are ships coming and going under the bridge, and ships parking at Richmond Long Wharf, next to noble little Red Rock. I occasionally spot spinnaker-ed boats chasing each other downwind, dinghies practicing on the weekends, or small motorboats at anchor when the fish are running. Completely by chance, I caught Cal Maritime’s training ship Golden Bear on its twice-a-year transit of the Bay, both departing for and returning from its summer cruise last year.

The Future

Given its waterfront location and idyllic Marin County perch, San Quentin Prison seems rife for relocation and redevelopment into high-density condos. The cynic in me thinks it’s an inevitability, but a local told me that the prison’s roots are too deep, and its architect, Alfred William Eichler, too famous to remove the historic facility.

It’s ironic that Marin, a county in a bubble of bucolic beauty, and a place that does not at all reflect the diversity that its majority white, wealthy, aging ex-hippie populace espouses, is home to the state’s oldest prison. Not to worry, Marinites, the prison is remarkably well hidden. You can briefly spot it from Highway 101, but otherwise, you can really only see it from here in the village, or from the water.

It’s ironic that only from paradise does purgatory comes into clear view.