San Quentin: Prison and Paradise on the Bay Area Shoreline

Standing on the shores of Point San Quentin, I imagine Mount Tamalpais, silhouetted in the distance, as an erupting volcano with rivers of lava flowing through what is now Corte Madera Creek, where the ferry commutes up and down the channel. If sped up into a time lapse, you’d see ice ages come and go, mastodons, indigenous people, settlers, sailors, and scoundrels, many of whom would end up here — like me.

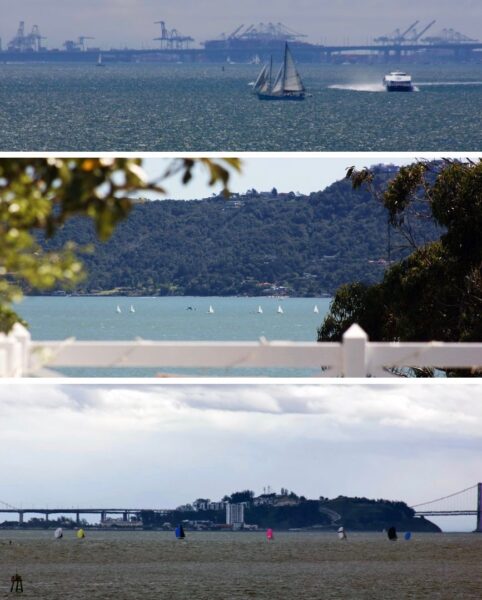

For nearly five years, I’ve been a resident of Point San Quentin, or San Quentin Village, a collection of houses tucked against the Richmond Bridge and the oldest prison in the state of California. Outside the gates and inside the Bay, it’s a busy intersection of ships, cars, bikes, ferries, windsurfers (like me), wingers, eFoilers, kayakers, rowers, dinghies and sailboats. In summer, gusty winds and shallow waters make for wild, confused seas; in winter it can be as glassy as a lake. San Quentin Village is both notorious and unknown, the kind of neighborhood you’d never know existed until you stumbled upon it. There are about 40 homes, a handful of condos, and 3,084 inmates inside San Quentin Penitentiary. After people give their predictably shocked looks when I tell them I live in San Quentin, they ask me if I’m affiliated with the prison, and if my house is inside the gates. (I’m not and it isn’t.) I’m just renting a reasonably priced room and working from home in a hidden-in-plain-site paradise perched against purgatory.

An Origin Story

Though California is defined by cities, towns and villages named after Roman Catholic saints, Point Quentin was actually named after the Coast Miwok warrior Quentín, who fought under Chief Marin — born as Huicmuse — while he was a prisoner at one of the iterations of the early penitentiary.

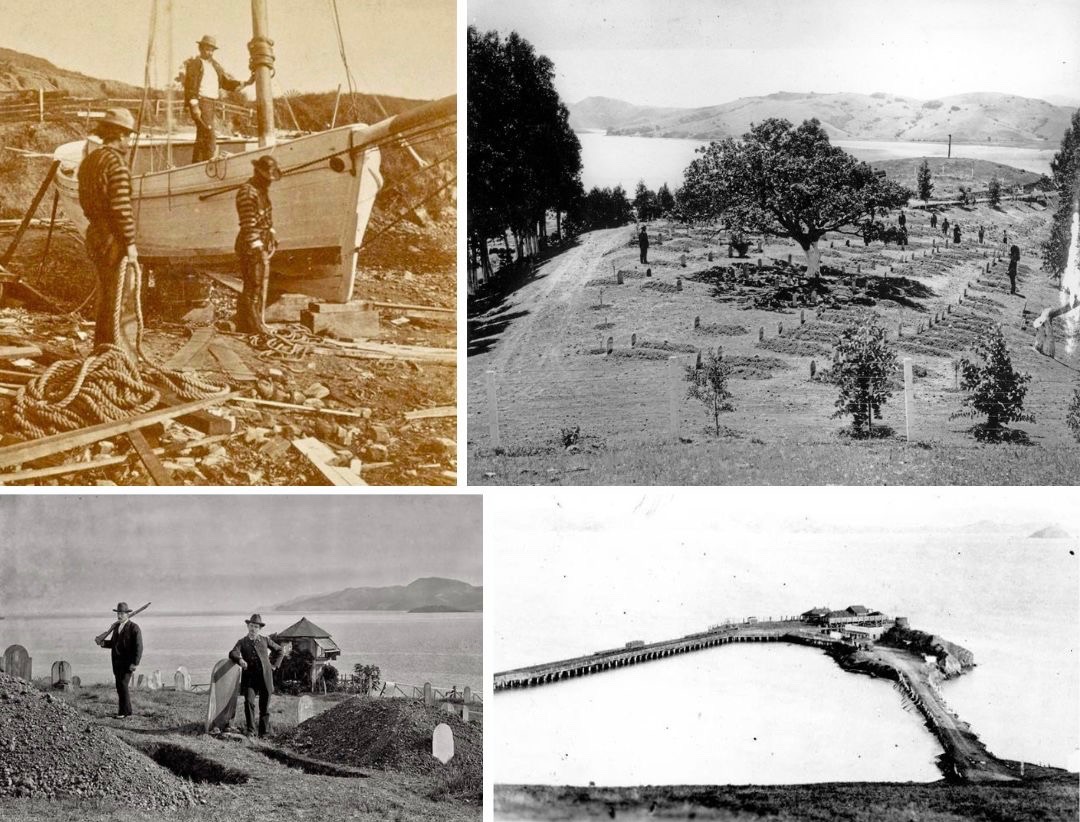

There were at least a few prison ships in the Bay Area in the mid-19th century, such as the brig Euphemia, which doubled as an insane asylum, according to San Francisco author Gary Kamiya. “Prisoners on the Euphemia anchored in San Francisco Bay and were sent ashore on a chain gang to do public works.” On July 14, 1852, the Waban, a 268-ton bark with some 40 convicts aboard, was towed across the Bay to Point Quentin. “Angel Island [the site of a quarry where prisoners worked], Alcatraz and Goat Island/Yerba Buena Island were the favored sites, but land-title problems led commissioners to choose Point Quentin,” Kamiya wrote. “The convicts were sent out during the day to work on the prison site, then locked up below decks at night. Four or five men were squeezed into each eight-foot-square compartment.”

San Quentin Village has seen numerous protests outside the gates of the penitentiary, including demonstrations against the death penalty, and objection to the state’s handling of a COVID outbreak in the prison. San Quentin is now morphing amidst a fundamental (and miraculously bipartisan) rethinking of the country’s criminal justice system. Governor Gavin Newsom’s administration has rebranded the prison as a rehabilitation center and is considering reducing the population, creating a vocational training campus, and building housing.

Latitude occasionally gets letters from prisoners in San Quentin and elsewhere. We’ve had requests for old issues, as well as general correspondence: Someone was teaching a navigation class at San Quentin; someone else sent us a small sketch of a crab-claw sail dinghy.

Sailing Chaos and Glory. But Mostly Chaos

When I first windsurfed off San Quentin Beach in 2020 and sailed on port tack toward the parking lot and hulking fortress of the penitentiary, I wondered if the prisoners could see me. Do inmates appreciate the view (if they have one), or is it cruel and unusual punishment to watch boats and windsurfers come and go freely?

Being able to windsurf from my house (the beach is 74 feet from my driveway) was a dream I didn’t know I’d always had. On a northwesterly breeze, I can launch from the beach and “slog” through the lee of the prison, then hit the windline and sail perpendicularly to Corte Madera Channel, into the mud off Paradise, rather than the prevailing parallel direction to the prison. It was thrilling!

And then it was humbling.

In anything over 20 knots, and on starboard tack, outbound into the Bay, there’s the prevailing steep, short-interval wind swell from the west, as well as another swell coming from the east — a kind of “rebound” bouncing off the Richmond Bridge. It is total chaos, and finding a clean line is tricky. One day in 2020, I dramatically underestimated the wind on a traditional westerly day, and the sail would rip out of my hands when I tried to water start. I came back to the beach panting and a little spooked. The very next time I sailed off San Quentin Beach, I’d done a few runs and was in a good groove when my brand-new universal, which connects the sail to the board, snapped in two. I was more than a mile offshore and had to paddle back.

San Quentin went from dream scenario to kind of sketchy. It’s usually a mogul-filled double black diamond, the kind of run that you endure rather than enjoy.

San Quentin has become a winging mecca, which makes sense: Foils just float over the chop. I’ve never tried it, but I plan to, soon.

The San Quentin Surf Forecast

Going to San Quentin Beach feels like visiting an actual beach, even though it’s on the Bay. It is, apparently, one of the few beaches in the Bay that allows dogs, which has created some tension with locals. (Parking is a huge issue.) I’m a dog person, so I don’t really mind, but the beach is a kind of barometer indicating population pressure — and the pressure is rising.

On glassy days, I enjoy prone-paddling a nine-ft fiberglass windsurfer off the beach and around the prison, or across the channel to Paradise. One day a few years ago, I was on the west side of the prison, near Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, when a ferry was inbound to Larkspur. The captain gunned it as they went by me, kicking up what (I swear to God) seemed like a head-high wave. I missed the first one, but caught the second and rode it for … maybe five to seven seconds before it petered out into deep water.

I tried chasing ferries for months afterward — at least 10 times — and have only been in position for a breaking wave once.

But I missed it.

The View From the Crow’s Nest

If “there is nothing — absolutely nothing — half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats,” then simply watching boats come and go must be a quarter as much worth doing (if my math is right).

Sometimes, it feels like I have a giant model-boat set next to me. There are windsurfers and wingers off the beach, there are ships coming and going under the bridge, and ships parking at Richmond Long Wharf, next to noble little Red Rock. I occasionally spot spinnaker-ed boats chasing each other downwind, dinghies practicing on the weekends, or small motorboats at anchor when the fish are running. Completely by chance, I caught Cal Maritime’s training ship Golden Bear on its twice-a-year transit of the Bay, both departing for and returning from its summer cruise last year.

The Future

Given its waterfront location and idyllic Marin County perch, San Quentin Prison seems rife for relocation and redevelopment into high-density condos. The cynic in me thinks it’s an inevitability, but a local told me that the prison’s roots are too deep, and its architect, Alfred William Eichler, too famous to remove the historic facility.

It’s ironic that Marin, a county in a bubble of bucolic beauty, and a place that does not at all reflect the diversity that its majority white, wealthy, aging ex-hippie populace espouses, is home to the state’s oldest prison. Not to worry, Marinites, the prison is remarkably well hidden. You can briefly spot it from Highway 101, but otherwise, you can really only see it from here in the village, or from the water.

It’s ironic that only from paradise does purgatory comes into clear view.

great writeup Tim..

An absolutely great article on San Quentin, and the surrounding area. I guess the argument of, “Not in my backyard”, doesn’t apply here, since it came first…