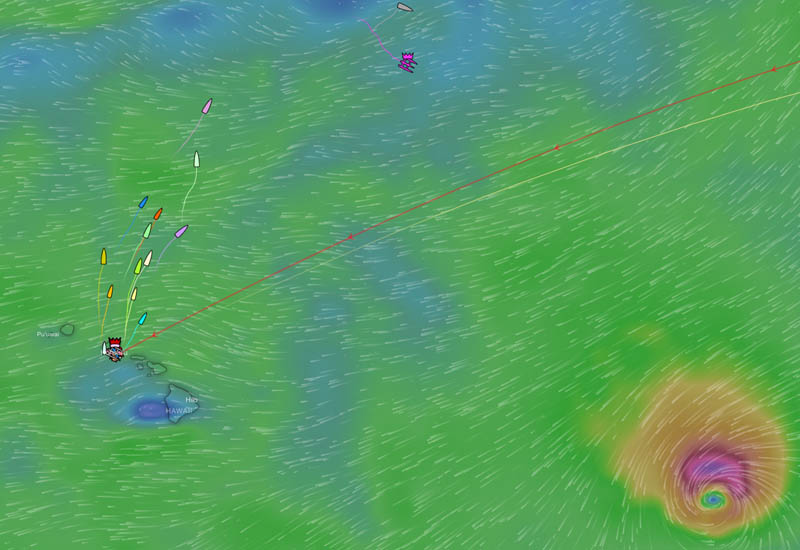

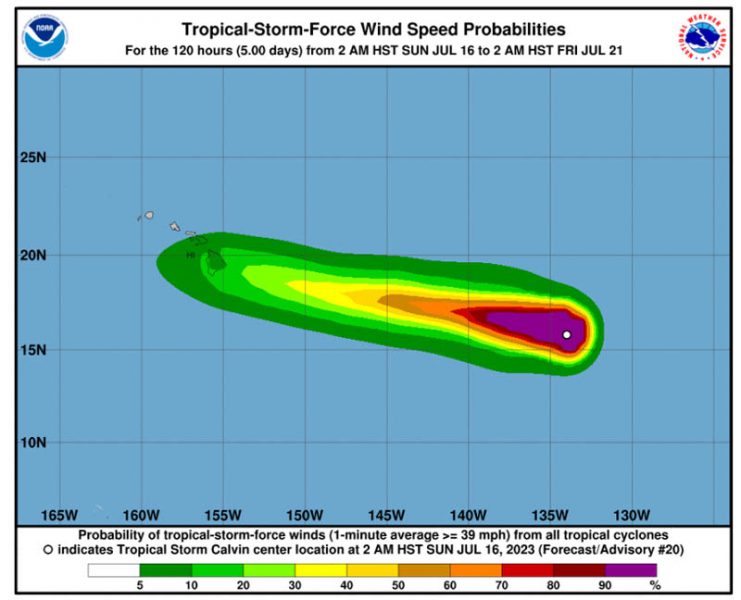

Hurricane Calvin Downgraded to Tropical Storm Calvin

Thankfully, Hurricane Calvin has been downgraded to Tropical Storm Calvin as it closes in on Hawaii. That’s good news for islanders, and for boats that recently arrived from the Transpac and the Singlehanded Transpacific Race.

Many of the boats in the race will be sailed home on their own bottoms, while others will be loaded onto a ship from sponsor Pasha Hawaii, with their race crews flying home. The trip home is tougher — it’s now an uphill ride as boats head north to get away from the easterly trade winds and look for westerlies circulating around the Pacific High.

While not a hurricane, Calvin could still cause some damage with heavy rainfall, strong winds, and big swells for boats and surfers. Hurricanes in Hawaii are rare, since it’s a small target and it’s on the edge of the Pacific High, which keeps the water just a bit cooler, thereby dampening the ability for the powerful storms to grow. There have been only 30 hurricanes that have come within 200 miles of Hawaii. The last one was Category 4 Hurricane Douglas, which caused damage in July 2020.

Safe passage to those sailing home and safe harbor for those riding it out in port.

Sailor Rescued in Southern Ocean Claims Collision With Sunfish

A 22-year-old sailor was on a circumnavigation of his home country, Australia, when he triggered his emergency beacon in the Great Australian Bight, approximately 630km from Kangaroo Island. (Yes, those are real geographical names.) Setting off from Queensland’s Gold Coast, Xavier Doerr was attempting to complete the circumnavigation in less than 50 days. At the time of his rescue he had been at sea for 64 days. The news reports are a little confusing, with one source saying his boat was struck by severe weather, and another writing that he had struck a sunfish.

The Australian news site 7news.com.au reported Doerr as saying, “I collided with what I believe was a sunfish underwater, which caused me to capsize and subsequently have a strong impact (to) my head.”

The sailor reported that he had sustained injuries and that his boat was damaged and taking on water, according to The Guardian.

Doerr reportedly spent almost 24 hours in what he describes as “extremely treacherous conditions.” Apparently a cargo ship made multiple attempts to bring him on board, and almost aborted the mission due to the 10m waves and 100km-per-hour winds. He did eventually board the ship, and from there was airlifted to the Royal Adelaide Hospital, where he was assessed for injuries.

The sailboat, described only as a “6.5-metre sailing yacht,” was recovered and towed to Port Lincoln, South Australia, where it was secured by locals.

The story leaves us with questions. One is related to the rumor that this was his second attempt at breaking the record of 58 days set by Lisa Blair in 2018, the first one also ending with a rescue. Is this true? We’ve not found the exact report to substantiate or refute the rumor. The second question is about the sunfish. Sunfish have been blamed for collisions in the past, as reported by Perth Now. But how can Doerr be sure? And was it the sunfish or the “extremely treacherous conditions” that caused the boat to be abandonded? Or perhaps both occurred simultaneously?

Doerr told 7news.com.au that “he will attempt the route again at some point in the future.” Let’s hope this time things go well and he makes it back to shore, with his boat. You can watch news clip video here.

Regardless of our confusion as to the facts of the story, we are of course thankful that the sailor is safely ashore and in good shape.

Discover Bair Island Marina in Redwood City

The Coronado 35 ‘Watchfire’ — A Season in the Delta

Between 1996 and 2000, Russel and Jennifer Redmond sailed their 26-foot Columbia sloop, Watchfire, around the Sea of Cortez for a year before heading south and through the Canal to Florida and back again to San Diego. After that, Watchfire became famous for having burned to ashes in a wildfire in San Diego’s backcountry; that sad ending was featured in Latitude. They eventually bought Watchfire 2, a Coronado 35, and sailed her to the S.F. Bay Area in 2020, and have since moved on to cruising Puget Sound. Jennifer wrote a book on the Columbia 26 adventures called Honeymoon at Sea: How I Found Myself on a Small Sailboat (Toronto), coming out in September. She wrote the following story about the months they spent in the Delta before heading on to the Pacific Northwest.

Russel and I had been in San Francisco’s South Beach Harbor Marina for two months, having arrived on Labor Day 2020. Our long-range plan was to take our highly modified Coronado 35 north to Puget Sound, but meanwhile, we enjoyed having Watchfire in a slip just outside the ballpark. That location was a dream for Giants fans like us, but now we were ready to explore the Delta for the first time. We left the marina on November 1 on a flood current, sailing across San Pablo Bay to the Carquinez Bridge. We were reminded of sailing in the Intracoastal Waterway of the Gulf Coast back in the ’90s as we navigated Carquinez Strait, under the bridges and into muddy, shallow Suisun Bay. The navigational waters are wide enough for huge container ships, so we stayed at the edge of the shallows on the starboard side, though we saw only one big tanker that day. Sailing down the near-empty channel with a light, steady west wind was relaxing, and we enjoyed the quiet after the noise of being in the ballpark’s backyard.

Back on the ICW we’d learned to stop early in the day, so that afternoon we nosed north out of the channel at the west end of Honker Bay and found an anchorage off tiny Snag Island in about two fathoms. We enjoyed the views of the faraway hills and the nearby field of motionless wind turbines while we dined, and soon settled down to sleep. First lesson: The wind turbines are put there for a reason!

By midnight the west wind was up, and so were we. Our Mantus anchor really digs in, so Watchfire stayed put, but between the boat’s movement and the keening wind, sleep was elusive. At dawn, it was gusting over 25 knots, which made cranking the anchor up with our manual windlass a bit of a challenge, but soon we were motoring past the now-spinning turbines out into the channel. The wind lessened as we went east, and at Pittsburg we turned onto the Sacramento River and sailed with the breeze.

That night we anchored in Horseshoe Bend at Decker Island, just shy of Rio Vista, so we could go into the marina the next morning on a slack current with calm wind, as is our custom. Having anchored with a west wind, we were surprised to see the current pulling us quite the opposite way an hour later (this was true in every anchorage during our time on the Delta). Again, our anchor always reset easily, and though our vistas changed constantly, we never dragged.

Continue reading at Latitude38.com.

The Resourceful Sailor Reinstalls a Classic Electronic Autopilot

It’s been a little while since we last heard from The Resourceful Sailor, but he’s back from his most recent sailing adventures, and we’re curious to find out what his latest boat jobs have entailed.

When I bought Sampaguita, a 1985 Pacific Seacraft Flicka 20 sailboat, in 2013, she came with a Navico Tillerpilot 1600 electronic autopilot. The previous owner claimed it did not work. It was wired directly to the battery without a fuse, and would strain the SeaVolt starting battery, which was also the house battery. Initially, I unhooked the wires from the battery for safety, coiled them up, and stowed them in the cockpit locker. The Navico, I put in dry storage.

It took me 10 years to see for myself if it worked. As my sailing programs and electrical system evolved, energy was less of an issue. As my storage space also changed, the Tillerpilot needed to be useful or be gone. Other boats I’d recently sailed on, Breskell and Inook in particular, had autopilots, and I was enlightened regarding their convenience. Buying a new unit for Sampaguita was unlikely, but if the one I owned already could be rejuvenated; that seemed sensible.

A previous owner had installed a cantilever bracket and power socket specific to the Tillerpilot 1600 on the side of the cockpit. I had left it in place all these years, and it was a sound and still relevant installation. I needed to safely rewire the connection to the battery, figure out if the claim of inoperability was correct, and install a new tiller pin.

First things first: I needed juice to test the unit. I reconnected the plug to the battery. With the updated electrical system, there was a fused power post. I kept it simple for testing purposes and would create a more permanent connection if the unit was operational. I plugged in the Navico and turned it on. At first, the actuator arm moved out and then retracted. Then it seemed to freeze and stay in the retracted-all-the-way-in position. However, I could hear a ticking sound from the unit as if it were trying to operate.

Since I had nothing to lose, I decided to look inside. Obsolete electronics from the 1980s hold no warranty. It was easy to open with nine straight-blade screws, and I was amazed at how simple and immaculate the innards were: still well-greased and clean. I attempted to understand how the unit worked and what might be causing it to bind in the retracted position.

I carefully inspected the arm, the gears, and the guide bars. They looked fine, with no bends or broken or distorted teeth. There appeared to be no visible reason for it to stick. So I muscled it. The moment it unstuck from the all-in position, the motor took over, and the arm began to operate again. Eventually, in its search to align its compass, the arm retracted, and it stuck again. Repeat muscling. Again it became operational.

Uncertain why it was doing this, I called it good. The answer might be not letting the arm retract to the stop. While it wasn’t a foolproof resolution, if I was the only fool using it, I knew the inside scoop. The fix, while a bit tedious, was known and could be repeated if the arm retracted and stuck. (Unless readers teach me better!)

Now that there was, at least for the moment, a functional autopilot, the wires were tidied and secured. The instrument plug was in the cockpit locker, where one of two separate house batteries was, so I decided to simplify things and maintain the connection at the fused power post rather than run it to the cabin circuit panel, which was at capacity. I could reassess this if the value-to-production ratio for an electronic autopilot changed in the future. A safe installation was the primary concern.

A search for compatible tiller pins on the internet turned up exactly what I needed. However, I did not accept what they were offering. You could buy a package of five for $20 plus shipping and tax. Why would I need five? Previously I had found a copy of the Tillerpilot 1600 and 2500 manual on the internet. (It is refreshingly retro, made on an old-school typewriter, typos and all, with simple but comprehensive drawings. I digress.) In its explanation of the installation of the tiller pin and its orientation to the unit, it mentions drilling a ¼-inch hole and epoxying it in. So I found an old ¼-inch stainless steel bolt in my stores. I cut, filed, sanded, and buffed it, using the old tiller pin, still in the now spare tiller, as a model.

On a 31-day Vancouver Island circumnavigation, I used the electronic autopilot twice. I would have used it at least another time previously, but locating the cantilever post thwarted me. It turned out to be in the bin where I thought it was, but finding it underway proved too troublesome. Of the two times, the first was on Queen Charlotte Strait, from Rough Bay, Malcolm Island, to Port Hardy, Vancouver Island. What started as an incredible day of sailing turned into a flat calm. An introductory experience with the Tillerpilot — it performed very well, and I enjoyed the experience. The second time came when approaching Hot Springs Cove on the west coast of Vancouver Island, fresh from three days and two nights offshore. The wind had died, but the swells rolling in from the ocean and the leftover chop remained. The 1600 did the work, but with much effort, noise, and meandering. The boat, left to itself under power, will always align with the direction of the swells, so the unit was in a constant battle. With a race against light, I took over and sent the Navico to bed.

The Resourceful Sailor still has to learn a bit about how to adjust the settings of the Navico Tillerpilot 1600 and when to use it, and remember that it is now an option after all these years. But this is really about reviving a pre-internet but functional artifact. It’s about keeping value, production, and investment in perspective. The best electronic autopilot might be the one you own already. Remember, keep your solutions safe and prudent, and have a blast.

Vallejo Marina: Gateway to the Bay, Delta, and Napa River

40′ to 45′ foot slips are now available at $9.97/ft. www.ci.vallejo.ca.us