The Women Navigators

In this month’s Latitude, author Michael Kew brings us a dispatch from the South Pacific island of Yap, which could be considered the heart of the modest Polynesian Voyaging renaissance that’s taken place over the last four decades. While attending “Yap Day” in 2017, Kew met with navigator Ali Haleyalur, the cousin of the great Pius “Mau” Piailug, who was a mentor of the Polynesian Voyaging Society in the 1970s, and would go on to captain and navigate Hokule’a, the famed 62-ft, 12-ton, full-scale fiberglass replica of a double-hulled voyaging canoe.

The Polynesian Voyaging Society’s literature about the trip said that, “When Hokule’a arrived at the beach in Papeete Harbor, over half the island’s people were there, more than 17,000 strong. There was a spontaneous affirmation of the great heritage we shared, and a renewal of the spirit of who we are today. On that first voyage, we were facing cultural extinction. We had no navigators left. The Voyaging Society looked beyond Polynesia to find Mau Piailug from a small island called Satawal, in Micronesia. He agreed to come to Hawaii and guide Hokule’a to Tahiti. Without him, our voyaging would never have taken place. Mau was the only traditional navigator who was willing and able to reach beyond his culture to ours.”

Mau was so “so highly regarded,” Kew wrote, “that, in 2016, three years after his death, Matson, Hawaii’s biggest ocean cargo transport company, christened its newest ship — Papa Mau — in his honor.”

But it isn’t just men who have been a part of this revival. Navigator Kala Tanaka was one of many sailors who have gone on to voyage on the Hokule’a since Mau’s day. “Kala’s father, Kalepa Baybayan, is a master navigator, and was one of the original crew members on Hokule’a,” according to gohawaii.com.

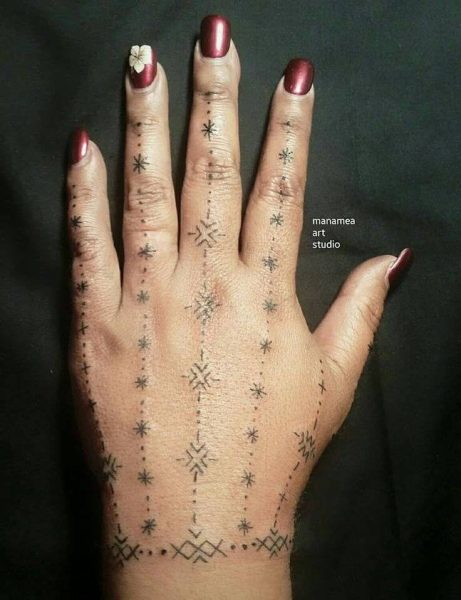

The photo above shows “brilliant navigator Tanaka measuring where she needs to go using her hand,” wrote Eliota Fuimaono-Sapolu on her Facebook page. “You might’ve seen Moana do a weird version of it. Many Samoan hand tattoos have fish around the wrists and the stars and togitogi up the fingers. The thumb lays across the horizon while the fingers stand vertical as you align your markings with the stars.”

An Update from Webb Chiles

Nation — Another solo circumnavigator sent us an update. We were delighted to hear from the legendary Webb Chiles, who, after a unique transit of the Panama Canal, is about to embark on the last leg of his sixth circumnavigation.

After a 17-day passage from Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, to Colon, Panama, that saw a 43 knot gale, the Bahamas become a dangerous lee shore, failure of three tiller pilots and the wind instruments, the port pipe berth sheer off the rivets attaching it to the hull, and far too many ships, Gannet, my Moore 24, was trucked across the Isthmus and is now on a mooring at the Balboa Yacht club almost prepared for what hopefully will be the final passage of her circumnavigation, the 3,000-mile sail partly against prevailing wind and current to San Diego.

Gannet presented insuperable problems for making the transit in the Panama Canal, which I have done three times previously in larger boats: There was no way to feed or sleep four line handlers, no sun shade for the advisor, no enclosed head, too small cleats for lock lines. Another problem, speed, could have easily been solved by renting or borrowing a bigger outboard.

I do not know if the Canal authorities would have permitted the little boat to be towed through by another yacht. No offer of a tow came forth, so I arranged for a cradle to be made and the truck ride. Gannet made the fastest crossing of any sailboat — at times clocking 43 knots — and probably the most expensive. I do not yet know the final total, but it will work out to be considerably more than $100 a mile.

The charge alone for the travel lift to put Gannet in the water was an outrageous $856.

I will not push hard against strong wind on the sail to San Diego. I will sail wide angles, slow down, even heave to and wait for favorable conditions. It is possible that I will divert to Hilo, Hawaii, which is easier to reach and where Gannet would also complete a circumnavigation.

I will probably sail next week, sometime between March 11 and 15.

For those who might be interested is seeing what happens, Gannet’s Yellowbrick tracking page can be found here.

The Cove – Boat Slips Available

Have You Seen This Painting?

Last week, this 30″x30″ oil painting sailed right out of its frame and disappeared over the horizon. We suspect the tall ship had a pirate at her helm. Actually, scratch that. “Pirate” makes the thief sound glamorous. This canvas was hijacked by a lowlife burglar. “A painting was stolen from the hallway at 125 Park Place in Point Richmond where I have my frame shop,” says Pam Delaney, the daughter of artist Jim DeWitt. “We think this happened Thursday morning” of last week. The Richmond police dusted the frame for prints on Sunday. “The person who did this took the painting out of the frame.” Pam asks that anyone who has seen the painting call her at (510) 206-0720 or email her at [email protected].

The artist, Jim DeWitt, was born in Oakland in 1930. He has lived and worked in Richmond since 1960. Jim operated a sail loft there for many years, but his passion for sailing has always included art. He studied at the California College of Arts and Crafts and at the Los Angeles Art Center in Pasadena. His paintings have graced galleries and museums worldwide, including the Sausalito Art Festival. Pam runs a custom frame shop and sells originals and prints of her dad’s artwork. We can’t remember an issue of Latitude 38 that hasn’t included something of or about Jim, be it a painting, an ad for sails, or a race report.

The Gennaker Tack, Part 1

I had been sailing Sampaguita, my 1985 Pacific Seacraft Flicka 20, for five years with a tedious setup for the gennaker, which meant I would rarely use it. The question I eventually asked myself was, “How do I modify the cranse iron on the bow to accommodate the gennaker tack for efficient flying and jibing of the sail?” After crewing on a few race boats, I picked up some ideas on how to improve Sampaguita’s setup.

For those who don’t know, a gennaker is a hybrid of a Genoa sail and a spinnaker. It’s a light-wind, lightweight, often colorful sail, like a spinnaker. However, the tack and the clew remain the same, like a genoa’s. You can use a pole, but unlike a spinnaker, it is not necessary — neither are the associated guy lines. It works well as a shorthanded, small-boat sail on a beam to broad reach in light to moderate winds. My gennaker also came with a “sock,” a very convenient accessory when shorthanding.

A cranse iron is a stainless steel or bronze fitting that is on the far end of the bowsprit. The forestay, bobstay and bowsprit shrouds attach to this iron as strong points. On Sampaguita, this iron has two topside attachment points, one for the forestay and one just aft of that for the jib or genoa. A long D-shackle attaches to the aft point, with a snap shackle attached to it. A jib or genoa tack snaps to this shackle and is a satisfactory setup for these headsails.

Formerly, I attached the tack of the gennaker to the same snap shackle used for the jib and Genoa sails. To gybe, I wind shadowed the sail with the mainsail and released its sheet. Then I went to the foredeck and doused the sail with the sock. Next, I unsnapped the sail’s pendant from the shackle, led it around the outside of the forestay and re-snapped it from the other side, and swung the socked sail over the forestay to match. Back to the cockpit, where I gybed the mainsail over and put the boat on a course that wind shadowed the gennaker in its new position. Again to the foredeck, I pulled up the sock and released the sail. Back to the cockpit where I adjusted course, allowed the gennaker to fill, and trimmed the sails.

Are you exhausted from reading that? Fortunately, the Flicka tracks well, but simplification was necessary to reduce tedium and time and increase safety and enjoyment. The single most important change would be to have the gennaker tack attached in front of the forestay. The sail could then be gybed from the cockpit with one smooth motion, eliminating travel to the foredeck and the associated actions.

A new cranse iron with an additional topmost attachment point was one solution. However, bronze casting and stainless steel manufacturing are costly. Another solution could be to install a roller-furling headsail system, which by attaching to the aft point on the cranse iron, would free up the forward one for the gennaker. The furling headsail would be an upgrade, but at great expense and labor. In addition to buying and installing the furler, a new headsail to fit would be necessary too.

Then it occurred to me to create a type of soft shackle using materials I had on hand. It would take about an hour to make, and I could add it to the existing setup. I figured it was worth a go.

Let me say this is not a soft shackle in the traditional sense, though the words fit the creation. First, I removed the long D-shackle used for the jib and genoa from the cranse iron so that I could work in a comfortable place. I also removed the snap shackle for the ease of handling. I found a piece of 5/16″, 3-strand nylon line about 12″ long that I had left over in my bag of “small stuff.” I chain spliced this line to each side of the D-shackle with the tucks meeting in the middle forming a 6″ loop. Carefully, I slid one of the chain splices from the shackle in a way that kept the lead space open. I would later reinsert the shackle into this lead. A pencil worked well as a placeholder. I returned the snap shackle to the D and added a snap hook over the spliced line. This last would be for the tack of the gennaker and would slide over the spliced line as the sail jibed from side to side.

This next step took concentration as I was working over the water. One slip could lose all three pieces of hardware in the canal. Up at the bowsprit, I led the spliced line on the outside of the forestay. I reinserted the D-shackle into the chain splice lead I had carefully kept intact and reinstalled the shackle to its original point on the cranse iron. The line forms a loop around the forestay on which the snap hook can freely slide from one side of the D-shackle to the other. Finally, I added whipping to the spliced line where the tucks met, securing and smoothing the area so the snap hook wouldn’t get snagged on them.

Readers — We’ll bring you Part 2 of Joshua Wheeler’s Resourceful Sailor Series: The Gennaker Tack, next week. If you have any thoughts on this bit of maintenance, please let us know.