The Shores of Richardson Bay

Another unfortunate soul is in a tough spot after their trimaran came to rest on the west shore of Tiburon this weekend. With full-moon high tides and a calm forecast, there’s hope that the boat will be able to refloat and find a longterm, secure location.

From our extremely unscientific observations, there seem to have been fewer boats blown loose from their moorings in Richardson Bay — and onto the rocks in Tiburon — this winter. The City of Sausalito has cracked down on boats in its waters, and has removed hundreds of derelict vessels over the last few years (the exact definitions of “derelict” and “marine debris” are a contentious point of debate). But the issue of safe, secure and environmentally friendly moorings for longterm anchor-out residents is a problem that’s far from settled.

Three Bridge Fiasco Preview

The chatter at yacht clubs this past weekend inevitably turned to strategy for next Saturday’s Three Bridge Fiasco. “Which way are you going to go?” is the question on the minds of the skippers (and doublehanded crewmembers) contemplating this crazy race. The premise of the Three Bridge Fiasco is complex in its simplicity. The simple part: Sail around three widely spaced fixed marks in any direction and order you choose. The complex part: The organizing authority (the Singlehanded Sailing Society) leaves the choice to each skipper.

Factors to consider include: wind predictions, current predictions, the behavior of boats starting before and with you, whether you’ll be on port or starboard at the start and at crowded mark roundings, whether you’re going to fly a spinnaker, and the particular characteristics of your own boat. Last but not least, where your homeport lies in relation to the course — in case there’s no wind and you decide to call it a day.

The race starts and finishes off the Golden Gate Yacht Club on the San Francisco Marina. Blackaller Buoy (near the south end of the Golden Gate Bridge), Yerba Buena/Treasure Island (bisecting the Bay Bridge), and Red Rock (near the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge) are the rounding marks on the nominally 21-mile course. It seems as if currents are always adverse for the Three Bridge Fiasco, with ebb in the morning and flood in the afternoon, but this year at least will not see a repeat of last year’s huge ebb that swept boats out the Gate. (That fate befell last weekend’s Corinthian Midwinters, which coincided with a full moon in perigee.)

The forecast calls for dry weather; it’s too early to predict what the wind will do. Latitude 38 has a new weather page on our website. Check it out at www.latitude38.com/weather. Tides are shown too.

Be sure to read the Notice of Race/Standing Sailing Instructions for the SSS season and the Three Bridge Fiasco Sailing Instructions. You’ll find these documents plus the online registration on Jibeset.

A few more tips:

- Check in on the appropriate VHF channel more than 10 minutes before your start time. Boats with sail numbers ending in an even number check in on VHF 70. Boats with sail numbers that end in an odd number check in on VHF 71. Be careful not to step on other transmissions. If you don’t hear a confirmation from the race committee, try again. If you’re using a handheld radio, maybe wait until you’re within view of GGYC.

- Make sure your running lights are in working order and remember to turn them on at sunset.

- The theory behind a pursuit race is that everyone starts at different times but finishes at the same time. Hence, finishes can be chaotic for the volunteers on the race deck. So make a note of your own finish time and the boat(s) that finished ahead and behind you, in case the race committee needs clarification.

- If you don’t cross the finish line, be sure to check out via VHF. If you don’t receive an acknowledgment from the race committee, call the SSS voice mail at (866) 724-5777. The volunteers can’t go home until they account for every boat.

- For the reason noted in #3, practice delayed gratification and cut the race committee some slack if the results aren’t posted immediately.

To glean more knowledge from minds greater and more experienced than ours, be sure to attend the skippers’ meeting (crews welcome too!) at Oakland Yacht Club in Alameda this Wednesday, January 23, at 7:30 p.m. Kame Richards of Pineapple Sails will talk about the currents. This meeting will feel like old home week to some who may not have seen their fellow competitors since before the holidays. Wednesday will also be the deadline to enter. Then show up on the Cityfront before your appointed start time (determined by your rating) on Saturday the 26th to join the 230 boats that have registered as of this morning.

OYC will host the awards presentation on Wednesday, February 6. Every racer gets a shirt, so everyone should go, whether they win — or even finish — the race or not.

We will of course have full coverage in the March — not February — issue of Latitude 38.

Ad: Rigging Specials at KKMI

New Record to the Equator

This morning at 07:45 UTC, Spindrift 2 broke her own record to the equator by just over an hour. The maxi-trimaran crossed the equator in 4 days, 19 hours, 57 minutes. Yann Guichard and his crew bettered their own record time for the stretch from the start off Le Créac’h lighthouse on Ushant (Ouessant) Island, set in 2015, by 1 hour and 48 minutes. This also gave the team an advantage of more than 23 hours (180 miles) over the current holders of the Trophée Jules Verne, Francis Joyon’s IDEC Sport. Thus the first goal in the team’s quest to beat the nonstop round-the-world record has been achieved. See our report last Wednesday, and follow the adventure at www.spindrift-racing.com.

One Hump or Two?

The sailing ships of old carried all sorts of cargos. But perhaps the most unusual shipment(s) ever carried by an American ship were loaded aboard 540-ton square-rigger USS Supply in the Mediterranean in the summer of 1855: camels.

It all started after the Mexican-American war (1846-1848) when the US gained the massive piece of real estate known as Alta California, which would later become all or part of the states of California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming. Someone suggested to Secretary of War Jefferson Davis — yes, that Jefferson Davis — that the military should try out camels. The thinking was that much of the lands west of the Rockies were desert, so maybe camels would be better suited for military duty than horses. Davis got Congress to fund the scheme — which brings us back to the USS Supply, docked at Tunis in the summer of 1855.

Now, ships had certainly carried livestock before. (You may recall that’s how horses got to the New World in the first place.) And Supply’s captain, Lt. David Porter, had seen to it that the ship was outfitted with special hatches and stable areas. But no one aboard really knew much about camels except what they’d heard — that when irritated, they would bite, kick, or spit a large, gelatinous wad of cud at you. They also had a pungent smell that scared the hell out of horses. As it turns out, all of these rumors were true.

Davis had appointed a Major Henry Wayne to lead the expedition, and Wayne did as due a diligence as he could. He went to London and Paris to visit zoos, and he conferred with camel experts, including British Army officers who had used camels during the Crimean wWar.

The United States purchased its first three camels in Tunis. It was later discovered that two were infected with ‘the itch’, a highly contagious form of mange. Oops. Fortunately, the captain’s brother-in-law, Gwynne Harris Heap, also came aboard at Tunis. Heap’s father had been a US consul in Tunis, so he spoke the language, knew the customs and had “a good working knowledge of camels.” He was a key figure in future negotiations, and no more itchy camels came aboard.

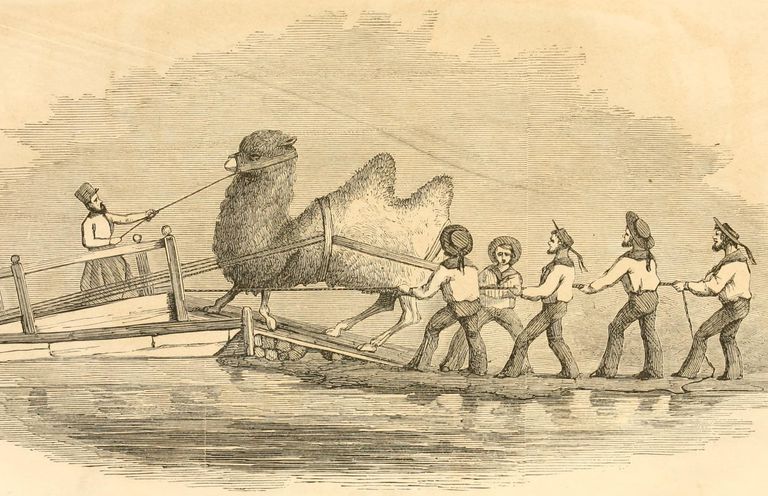

Loading the camels — which, depending on type and age, weigh between 800 and 2,000 pounds — involved a small barge fitted with a ‘camel car’. The latter was a large, fenced cart with iron gates at either end. The idea was to coax the camel onto the car and barge him out to the anchored ship, where he was hoisted aboard with a sling. If the camel couldn’t be coaxed, a group of sailors dragged him onto the camel car with block and tackles, doubtless with a lot of kicking and spitting involved.

The Supply made several stops around the Med to secure a full complement of camels. When it finally departed for home in February 1856, there were 33 aboard. Most were dromedaries (one hump), although three were Bactrian (two-humped). The former were renowned for their swiftness; the latter for their strength and burden-carrying abilities.

Also aboard were enough hay, oats and water for the two-month trip back to the States, as well as six Arab camel drivers. Oh, and camel saddles — a bunch of camel saddles since, as Captain Porter wrote, “It was certain that properly fitting saddles could not be obtained in the United States.”

Aboard ship, the camels were stabled belowdecks. By order of the captain, the animals were fed and brushed once a day, and their stalls cleaned daily. During heavy weather, the camels tolerated being tied to the deck in their knelt-down resting position for days.

One adult camel died during the crossing. Six were born, but only two survived. Those youngsters had the run of the ship and endeared themselves to the crew. Curiously, they managed the movement of the ship fine, even in the heavy weather that so affected the balance of the adults.

The Supply landed in Indianola, Texas, in May and unloaded 34 camels. (One more than they’d started with due to the above math.) All the surviving camels were in better health and spirits than when they had boarded. Apparently, humans aren’t the only ones who are invigorated by a good sail.

No sooner had the Supply crew unloaded the camels and cleaned the ship up, than they were ordered back to the Med for more. The second shipment of 41 camels arrived in Mississippi in February, 1857.

The Army conducted several experiments using the camels as pack animals, including a 650-mile trek from Fort Defiance (on the present NM/AZ border) to Los Angeles. The results surprised even the most doubting cavalry officers — camels excelled over horses in almost every way. They could carry heavier loads, traverse more rugged terrain, and go longer and farther between being fed and watered. They were even better swimmers: When crossing the Colorado River, all 25 heavily loaded camels made it, while two horses and 10 mules drowned.

The Camel Corps experiment ended with the outbreak of the Civil War. The camels were eventually auctioned off, to spend the rest of their lives in circuses, giving rides to children, living on private ranches, or working as pack animals for miners and prospectors — including possibly a few ’49ers in California. For years afterward, wherever they appeared, the camels continued to attract the curious and stampede the horses.