One Hump or Two?

The sailing ships of old carried all sorts of cargos. But perhaps the most unusual shipment(s) ever carried by an American ship were loaded aboard 540-ton square-rigger USS Supply in the Mediterranean in the summer of 1855: camels.

It all started after the Mexican-American war (1846-1848) when the US gained the massive piece of real estate known as Alta California, which would later become all or part of the states of California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming. Someone suggested to Secretary of War Jefferson Davis — yes, that Jefferson Davis — that the military should try out camels. The thinking was that much of the lands west of the Rockies were desert, so maybe camels would be better suited for military duty than horses. Davis got Congress to fund the scheme — which brings us back to the USS Supply, docked at Tunis in the summer of 1855.

Now, ships had certainly carried livestock before. (You may recall that’s how horses got to the New World in the first place.) And Supply’s captain, Lt. David Porter, had seen to it that the ship was outfitted with special hatches and stable areas. But no one aboard really knew much about camels except what they’d heard — that when irritated, they would bite, kick, or spit a large, gelatinous wad of cud at you. They also had a pungent smell that scared the hell out of horses. As it turns out, all of these rumors were true.

Davis had appointed a Major Henry Wayne to lead the expedition, and Wayne did as due a diligence as he could. He went to London and Paris to visit zoos, and he conferred with camel experts, including British Army officers who had used camels during the Crimean wWar.

The United States purchased its first three camels in Tunis. It was later discovered that two were infected with ‘the itch’, a highly contagious form of mange. Oops. Fortunately, the captain’s brother-in-law, Gwynne Harris Heap, also came aboard at Tunis. Heap’s father had been a US consul in Tunis, so he spoke the language, knew the customs and had “a good working knowledge of camels.” He was a key figure in future negotiations, and no more itchy camels came aboard.

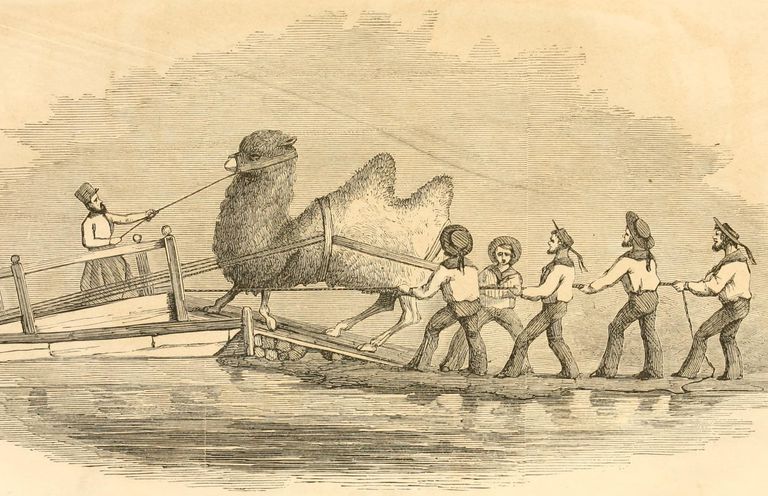

Loading the camels — which, depending on type and age, weigh between 800 and 2,000 pounds — involved a small barge fitted with a ‘camel car’. The latter was a large, fenced cart with iron gates at either end. The idea was to coax the camel onto the car and barge him out to the anchored ship, where he was hoisted aboard with a sling. If the camel couldn’t be coaxed, a group of sailors dragged him onto the camel car with block and tackles, doubtless with a lot of kicking and spitting involved.

The Supply made several stops around the Med to secure a full complement of camels. When it finally departed for home in February 1856, there were 33 aboard. Most were dromedaries (one hump), although three were Bactrian (two-humped). The former were renowned for their swiftness; the latter for their strength and burden-carrying abilities.

Also aboard were enough hay, oats and water for the two-month trip back to the States, as well as six Arab camel drivers. Oh, and camel saddles — a bunch of camel saddles since, as Captain Porter wrote, “It was certain that properly fitting saddles could not be obtained in the United States.”

Aboard ship, the camels were stabled belowdecks. By order of the captain, the animals were fed and brushed once a day, and their stalls cleaned daily. During heavy weather, the camels tolerated being tied to the deck in their knelt-down resting position for days.

One adult camel died during the crossing. Six were born, but only two survived. Those youngsters had the run of the ship and endeared themselves to the crew. Curiously, they managed the movement of the ship fine, even in the heavy weather that so affected the balance of the adults.

The Supply landed in Indianola, Texas, in May and unloaded 34 camels. (One more than they’d started with due to the above math.) All the surviving camels were in better health and spirits than when they had boarded. Apparently, humans aren’t the only ones who are invigorated by a good sail.

No sooner had the Supply crew unloaded the camels and cleaned the ship up, than they were ordered back to the Med for more. The second shipment of 41 camels arrived in Mississippi in February, 1857.

The Army conducted several experiments using the camels as pack animals, including a 650-mile trek from Fort Defiance (on the present NM/AZ border) to Los Angeles. The results surprised even the most doubting cavalry officers — camels excelled over horses in almost every way. They could carry heavier loads, traverse more rugged terrain, and go longer and farther between being fed and watered. They were even better swimmers: When crossing the Colorado River, all 25 heavily loaded camels made it, while two horses and 10 mules drowned.

The Camel Corps experiment ended with the outbreak of the Civil War. The camels were eventually auctioned off, to spend the rest of their lives in circuses, giving rides to children, living on private ranches, or working as pack animals for miners and prospectors — including possibly a few ’49ers in California. For years afterward, wherever they appeared, the camels continued to attract the curious and stampede the horses.

Check out the classic film (loosely) based on this true story: Hawmps! https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0074614/