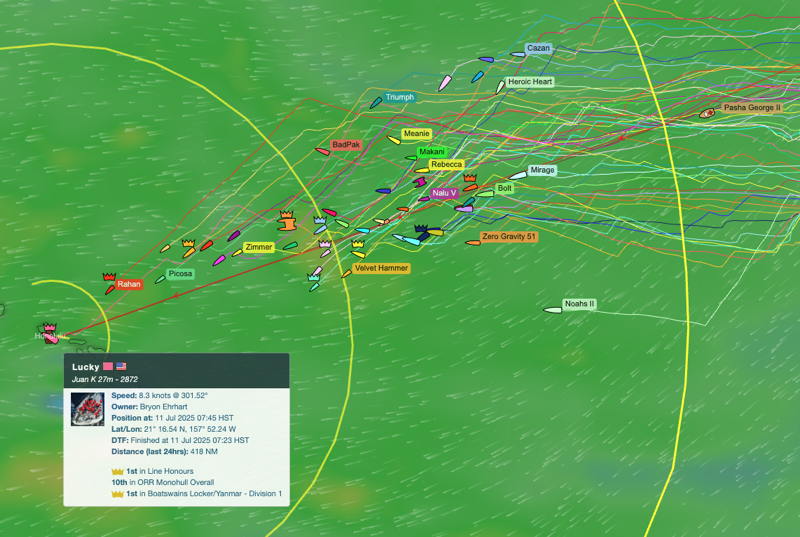

Transpac 2025: ‘Lucky’ Grabs the Barn Door at 0723, More Boats Arriving This Weekend

Transpac racers surfed toward the tropical islands under a full moon last night, while positions are getting sorted as the breeze evens out across the course and the fleet starts to converge on Hawaii. It was yesterday evening that the big boat, Lucky, snatched the line-honors position from the Beneteau First 36 Rahan as she powered past at almost 20 knots. For a while it was looking as if Rahan could stay ahead to get line honors until Lucky passed them with just with just 340 miles to go. And it was Lucky that surfed across the finish line at 0723 this morning to grab the Barn Door Trophy.

The light breeze in the middle of the race split the fleet three ways, with some going low to avoid it, some going high, and some just suffering through it. The Tuesday starters were the lucky ones who slipped by the slow blue blob before it formed, with the Thursday and Saturday starters facing the strategic puzzle.

All the boats have now crossed the halfway point, and those who were lucky got to open their halfway gift boxes. The “five o’clock shadows” are starting to be full-fledged beards, so perhaps some of the razors will get used. The gift boxes come from family and friends, and contain cards, snacks, rum, and whatever else gives tired crew mid-race inspiration.

Transpac YC Rear Commodore Alli Bell on her Cal 40 Restless continues to lead Division 9, while Andy McCormack’s Reichel/Pugh 68 Pied Piper has moved up to steal first overall in ORR Monohull, dropping Restless to second overall.

An update from Greg Dorn’s TP52 Favonius 2 highlighted the change in the weather, remarking on heavier breeze and better boat speeds. Greg said, “With sustained speeds in the 17- and 18-knot range and regularly touching 22 knots, the boat is planing beautifully. A 52-ft, seven-ton boat planing through waves, surfing down wave backsides, and zipping along essentially nearly level in flatter segments is an incredible sight.”

Meanwhile, crew Matthew Sessions and Ashley Perrin reported on some mid-ocean repairs, including replacing an exploded spinnaker block, re-priming the watermaker, and releading a wayward mainsheet block. The boats are put through the stress test 24/7 for well over 2,000 miles, and things break.

When asked about the squalls that often feature prominently in the Transpac, Tom Furlong, owner and skipper of the Reichel/Pugh 52 Vitesse, described this year’s race as an outlier. “No squalls that are significant,” he said during an at-sea interview. “We’ve had little spates of rain here and there, but it’s not the squall-squalls that we’re used to, where you get a six- or eight-knot increase in breeze and really hard rain.

“We’re getting into territory now where we’re seeing some of the higher breeze,” Furlong reported. “It’s what these planing boats want — you want to get into that breeze and really start planing. I was driving last night for a little while with just under 20 knots of breeze, and it was a really nice evening.”

“The last 24 hours have been great,” said Ivan Batanov, owner and skipper of the Reichel/Pugh 51 Zero Gravity 51. “We’ve seen really nice conditions, mostly in the 16-18-knot range, and we’re pointed straight at Hawaii.”

As of yesterday evening, the crowns on the leaders on the tracker looked like this (subject to change!):

Boatswain’s Locker/Yanmar Division 1 • Badpak – Botin 56, owned by Tom Holthus

Mount Gay Division 2 • Fast Exit II – Ker 52, owned by John Raymont

Whittier Trust Division 3 • Pied Piper – Reichel/Pugh 68, owned by Jack Jennings

Cal Maritime Division 4 • Aimant de Fille – J/145, owned by Steven Ernest

Cabrillo Boat Shop Division 5 • Westerly – Santa Cruz 52, owned by Dave Moore

Garmin Division 6 • Arsenal – J/125, owned by Andrew Picel

Suntex Division 7 • Rahan – Beneteau First 47.7, owned by Fred Courouble and Charles-Etienne Devanneaux

Pasha Division 8 • Macando – Beneteau First 47.7, owned by Mike Sudo

Bridger Insurance Division 9 • Restless – Cal 40, owned by Alli Bell

smithREgroup Multihull Division • Convexity2 – Gunboat 68 (multihull), owned by Don Wilson

Dave Moore’s Westerly was first in class and first overall in 2023 and looks to be headed for a repeat as they close in on the final 600 miles.

Lucky turned on the afterburners with less than 300 miles to go, and as predicted by navigator Stan Honey, she finished the 2,225-mile race early this morning with the rest of the boats, especially Tuesday starters, hot on her heels.

The rest of the fleet should begin sailing by the finish off Diamond Head starting Sunday morning. Follow them here.

Caption Contest(!)

We dug this photo out of the archives. It was sent to us by John Dukat in 2020. “Having once been a foredeckman, I have great sympathy for that poor dude going over the side into an uncertain future, which might include a hard landing.”

Look up the June Caption Contest(!) winners in this month’s Loose Lips, here.

Your Local Sail Experts Marchal Sailmakers Are Back

Will the SHIPS Act Revitalize Vallejo’s Maritime Industry?

“I absolutely hope that it begins right here in Vallejo. Shipbuilding is in the DNA of our region,” Congressman John Garamendi said in an interview. Garamendi, whose district spans from Richmond to Fairfield, is sponsoring a bill that seeks to revitalize the nation’s maritime industry. Named the SHIPS for America Act (SHIPS Act), the bill will channel federal investment and oversight into the maritime sector.

“The SHIPS Act would revitalize the maritime industry in a variety of ways,” Garamendi said, primarily by investing in the maritime academies and financially stimulating the local shipbuilding industry. The stakes, he explains, are national. “We built five ships and they built 5000,” Garamendi said of China’s shipbuilding industry. “They are dominating the shipping industry and the national security issues associated with that.”

These concerns, and potential business, have garnered increased attention from local communities and big-money investors alike. One such player is the California Forever project, which recently purchased 50,000 acres near Rio Vista to build a new city and shipbuilding port. Vallejo and its leaders also feel they have a part to play, wondering how the maritime industry could return to Mare Island, which was the oldest shipyard on the West Coast before it closed in 1996.

“I support the SHIPS Act and I definitely see opportunity for us to grow our maritime industry,” Vallejo mayor Andrea Sorce said in an interview. “We are in active conversations to ensure that we make the best of the opportunities presented by this legislation.” Garamendi wants shipbuilding to come back to his district: “I think the people of Vallejo have the knowledge, the desire, and the spirit to begin addressing these problems,” he said. Shipbuilding, however, is “the one element that takes the most time, that’s going to be the most critical,” he explained. The more addressable half “are the mariners themselves.”

When asked how the development of shipbuilding and Cal Maritime would work together, Garamendi answered, “That’s easy: Mare Island builds the ships, Cal Maritime trains the mariners to crew them.”

California State Maritime University, located in Vallejo, is one of seven US merchant marine academies and the only one on the West Coast. A new training vessel, the Golden State, is expected to arrive at Cal Maritime in 2027. Provided by the US Maritime Administration, it will double the academy’s licensing capacity. A $126 million pier and upgraded electrical system are planned to accommodate it.

In an interview with Cal Maritime dean of engineering Dr. Dinesh Pinisetty, the dean said he hopes to increase the merchant mariner licensing program from its current 600 to a potential 1000 cadets.

Garamendi has said the SHIPS Act will provide funding for those educational programs. In exchange, the congressman specifically wants Cal Maritime to expand its local recruitment efforts. He believes it could be achieved if only people knew of the opportunities that the university offers, telling Cal Maritime to “put them on a bus!”

According to Dr. Pinisetty, 80 percent of cadets are male, and most come from Southern California. All the while, admissions have been diminishing, even before the COVID pandemic hit. Between the infrastructure on Mare Island and the well-trained Cal Maritime workforce, “It would be an ideal marriage,” Pinisetty said. “We can change the culture, change the economy of Vallejo, if we can bring shipbuilding back.”

While there is no expectation that shipbuilding on Mare Island will return to the former glory of its Navy days, advancements in technology and manufacturing processes could open doors for new industries.

“China has doubled their infrastructure significantly, where they can build a ship in a few months. If we are trying to compete with someone who is, like, 40 years ahead of us, we need to rely on technology and use it very strategically,” Pinisetty said. The future of shipbuilding is likely to be modular, he explains, with parts being built all over the world and assembled in large ports. Mare Island could be one such constructor, supported by Cal Maritime’s workforce.

Regardless, investment in infrastructure and industry would be required, hinging on Congress’s approval and local leaders’ support. The stakes are national, but the opportunity is local.

Max Ebb — In Praise of Raster

One of the lost pleasures of planning a trip to a new sailing area was rolling out the new charts. A physical chart that covered most of the dinner table evoked the adventure, the hazards, and the rewards of a cruise. But times have changed. The charts are digital, and the largest chart is only as big as your screen.

Our local sailing school and its affiliated “club” were planning a charter flotilla, and tried to get around this limitation by projecting the charts on the big screen in the yacht club bar. Lee Helm, naval architecture grad student and ace navigator, had been tapped to help with the navigation lecture — especially the nuances of digital charts. Many of these sailing-school people are more or less novice cruisers, despite their age. “Seems a shame that they had to wait till retirement to learn to sail,” I often thought. But this class was pretty sharp, and some of them had been sailing back in the day.

“Digital charts have, like, more info, but you have to take some time to learn their care and feeding,” Lee began. She stopped for questions after a few charts of the flotilla cruising grounds were projected on screen, with various options turned on or off.

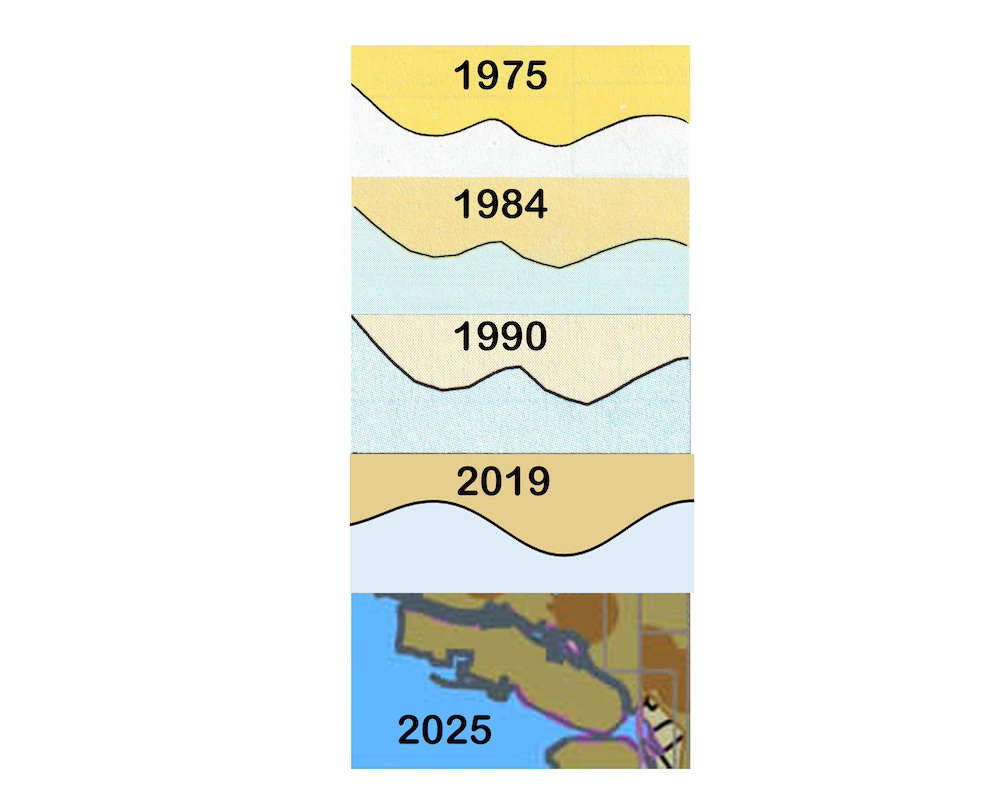

“I miss the color of land in the old paper charts,” one of the older-sounding voices in the darkened room remarked. “The charts used to show land as bright yellow, like the color of a sandy beach in sunlight. Made me really look forward to going there.”

“Me too,” another cruiser waxed nostalgic. “It was in the mid-’70s that they took away the sunlight and went to a dull shade of yellow. Then to an even duller tan color, supposedly to conform to international standards.”

“And now the digital charts paint the land with a color that looks like abandoned industrial shoreline,” complained another sailor. “Not that that isn’t what a lot of our urban shoreline actually is, but still, the color choices should make the charts appear to describe places we want to sail to, not Superfund sites.”

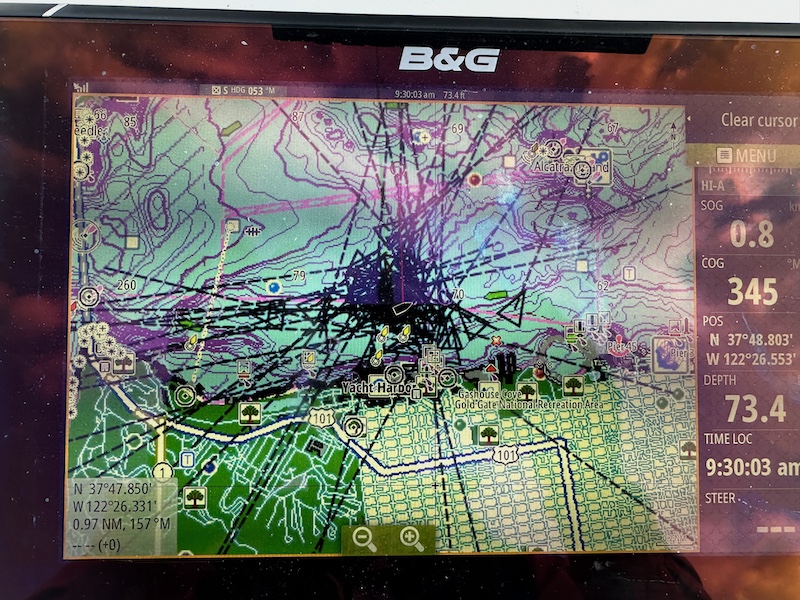

“Standardization, like, reduces errors,” Lee tried to defend the digital chart conventions. But the room was clearly not with her. “Forget the aesthetics; you have to be very careful with the zoom level,” Lee continued, trying to stay on topic. “It’s like, an artifact of adapting the charts to small screens. Zoom out too far, and hazards can disappear from the map. Zoom in and you can lose track of the overall navigation strategy. Zoom out again and you have to deal with overlapping text and other kinds of clutter.”

“Wasn’t there a round-the-world racer who put their boat on the bricks because their chart was zoomed out too far?” asked a younger voice in the group.

Read.