As Oakland Estuary Sees Improvement, Cities Around the Country Deal With Derelict Vessels

After a harrowing summer of what was dubbed a “pirate crime spree” on its shores — and after several years of lax enforcement by police — grant money has poured into the Oakland Estuary, marine units are back on patrol, and at least 25 derelict vessels have been removed. “Eighteen were taken from the waterway and crushed,” said former harbormaster Brock de Lappe. “Seven left on their own accord to other parts of the Bay; two anchor-outs have been eluding enforcement by moving back and forth across the Estuary from Oakland to Alameda.”

As we reported on Monday, a sailboat apparently broke loose and slammed into a breakwater in Alameda, where it eventually sank. It’s not clear if this boat was one of the roaming anchor-outs described, but regardless, de Lappe said that the City of Alameda will be contracting a salvager to remove the wreck.

While there’s been a long-running debate over anchor-outs in the Bay Area, the problems here are by no means unique. “You’ll have vagrants squatting on the boat [and] it falling apart; there have been several instances where the boats have come loose and ran into docks,” said a sheriff in Martin County, Florida, just north of West Palm Beach. In an attempt to target boats in the Miami area, a Florida state bill proposes to ban overnight anchoring for all vessels in parts of Biscayne Bay. Cruising advocates are up in arms over the bill, but the pressures of homelessness continue to collide with boating interests, infrastructure, and boats themselves. Once a vessel has fallen into disrepair or reached the end of its useful life, it’s worth nothing on the market, but has a huge price tag for disposal and removal — especially if it’s wrecked in the water. Such a vessel, however, is invaluable to an unhoused person seeking shelter.

In last month’s Sightings, we noted the strange sense of déjà vu on the Estuary: There was a $7 million cleanup of derelict vessels in 2013, where some 50 boats — including as many as 25 liveaboards — were removed. Up until 2019, the lone Oakland Police marine unit was still patrolling the Estuary and tagging boats. After a lawsuit against the Oakland PD in 2019, there was virtually no enforcement until late last year. The number of anchor-outs boomed in the interim. Brock de Lappe has long maintained that as long as there’s rigorous enforcement, anchor-outs can’t take root again.

Only time will tell how the cities of Oakland and Alameda manage and patrol the Estuary. Oakland marine officer Kaleo Albino “made the plea that temporarily assigned OPD personnel become permanently assigned to the marine unit so that he can maintain regular on-the-water patrols to protect the Estuary from the problem recurring,” de Lappe said.

“For the record, the Estuary is now the cleanest it has been in years,” he added.

Though theft appears to have subsided, a work/tow boat was stolen from Alameda Marina a few weeks ago. “It was found along the Oakland side of the Estuary at an encampment near Coast Guard Island,” Eileen Zedd, the harbormaster at Alameda Marina, said in an email. “We retrieved the vessel along with other stolen property. We made a report with [Alameda Police Department]. Of course, they said for the other items on the other side we would need to contact Oakland PD.”

There are hundreds of thousands of boats registered in California — the fourth-most in the nation — according to the Mercury News. “The state’s $10 billion recreational boating community supports tens of thousands of jobs. But the state has few comprehensive plans for disposing of aging or abandoned boats. In order to gain ownership of the abandoned boat, allowing them to access funds that will help them remove it, marinas must undertake a months-long lien process. They may have to pay hundreds or even thousands in back taxes to the county. Meanwhile, the boat takes up a slip, no longer making any money for the business. To avoid that outcome, some marina operators have long sold abandoned boats to interested buyers for as little as one dollar,” thus proliferating the fleet of derelict vessels/homeless shelters.

“There’s this cycle that repeats itself,” Alameda harbormaster Eileen Zedd told the Mercury News. “It’s hard for marina operators to deal with these situations. There’s just not much help out there.”

While the Oakland Estuary has long been a recreational hub for sailors, paddlers, swimmers, etc., it’s not necessarily a cruising destination — certainly not like Biscayne Bay.

“These anchorage grounds are often used by responsible cruising boaters for re-provisioning and waiting for a safe weather window as a jumping-off point for the Bahamas and Caribbean,” Cruising World wrote. With two bills set to go into effect on July 1 that would ban overnight anchoring within 200 yards of seven islands in Biscayne Bay, the state of Florida is “struggling to balance the rights of responsible boat owners against the owners of poorly maintained, derelict vessels,” Cruising World said, echoing identical concerns seen here in the Bay. “These vessels, which have little to no value, wash up ashore and are frequently abandoned after storms, leaving taxpayers to foot the bill for removal.”

“It can be anywhere from $6,000 and upwards,” the Martin County sheriff said of salvage operations. “Astronomical amounts of money.”

Boating advocates in Florida are urging people to write lawmakers in protest of the proposed bill. BoatUS described the proposed anchor ban as an ineffective, whack-a-mole approach. “The reality is these bills will do nothing to decrease the number of derelict and at-risk vessels in Biscayne Bay; these boats will simply move to other areas. Using state law to prohibit anchoring takes away public access to a shared resource for the benefit of only a few waterfront property owners.”

“We’ve seen a tremendous increase, actually, throughout the county,” said the Martin County sheriff of derelict vessels. Fox News added, “Authorities [in Florida] cite cost of living issues for the increase of squatters and homeless people moving onto the boats.”

US Racers Ronnie Simpson and Cole Brauer in South Atlantic in Global Solo Challenge

There are very few Americans who have competed in, and completed, singlehanded round-the-world races. Former Bay Area resident Bruce Schwab was the first American sailor to complete the Vendée Globe in 2004/05. There are now three Americans competing in the singlehanded Global Solo Challenge. Both Ronnie Simpson and and Cole Brauer have returned to the Atlantic by rounding Cape Horn, and David Linger from Seattle, aboard his Class 40 Koloa Maoli, is about 600 miles from rounding.

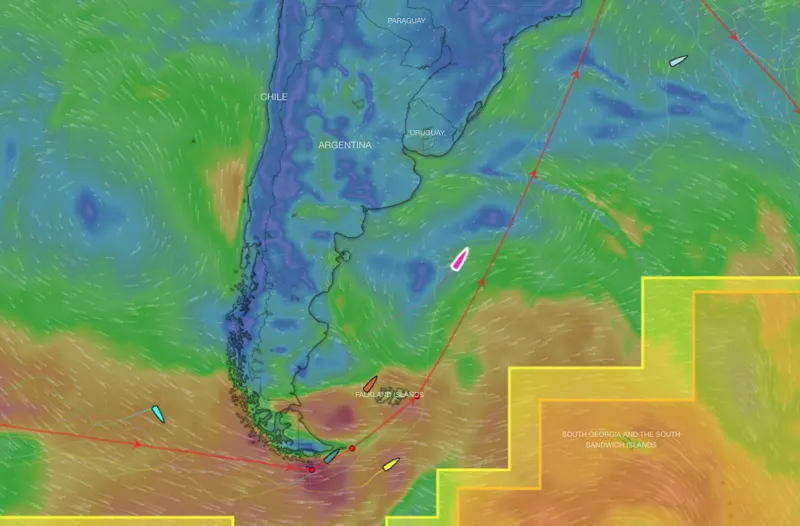

The tracking map from the Global Solo Challenge above shows the difficulties faced by racers as they navigate Cape Horn and the weather systems. To us, they look like an expanded version of the breeze and wind holes in the recent Three Bridge Fiasco. Cole Brauer aboard First Light is the pale blue boat in the upper right, Ronnie Simpson aboard Shipyard Brewing is the fuscia boat approaching the calm blue 1200 miles behind Cole, and David Linger aboard Koloa Maoli is the green boat to the west of Cape Horn, another 1500 miles behind Ronnie.

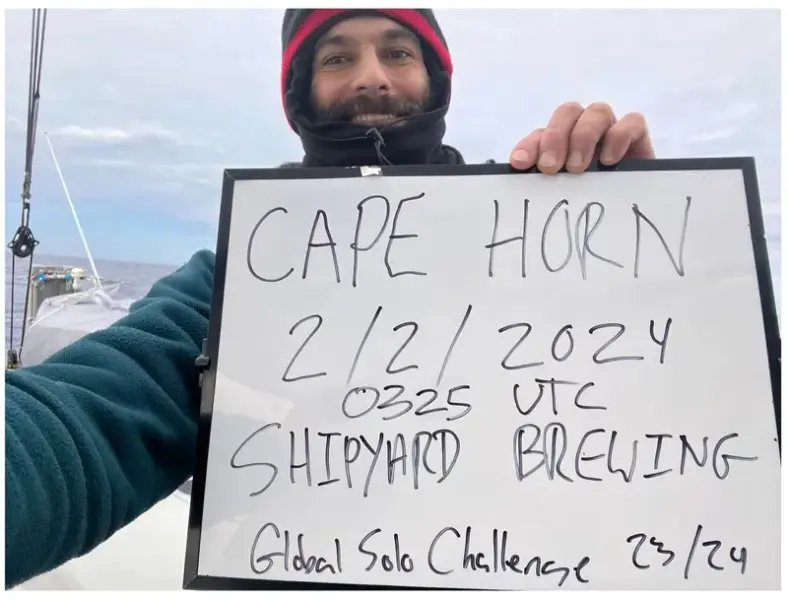

Ronnie’s rounding of Cape Horn came in the dark at 0330 UTC, with heavy seas and winds of up to 60 knots. Ronnie reported to the Global Solo Challenge that Shipyard Brewing rounded with no mainsail and just a storm jib. He made a wide arc around the Cape in the heavy breeze to stay off the continental shelf’s shallower waters. He got no breaks following the rounding. North winds were powering down the eastern coast of Argentina, causing him to sail through the Beagle Channel and stay close to the coast to avoid the stronger, adverse winds offshore.

Ronnie and Shipyard Brewing are also representing US Patriot Sailing in their quest to be one of the very few Americans to successfully race solo around the world. He was forced to make a pit stop in Hobart, Tasmania, for repairs, but was able to turn around in about four days to retain his third-place position. Now back in the Atlantic, he’s heading to warmer weather on the 1600-mile leg home to the finish line in A Coruña, Spain.

Running in second place in the race behind leader Philippe Delamare aboard Mowgli is the only female competitor in the race: Cole Brauer. Cole has given an outstanding performance, rocking the race aboard her Class 40 First Light. She is now 4800 miles from her goal of becoming the first American woman to complete a solo race around the world. At 5′ 2″, 100 lbs and 29 years old, she’s a fresh face of female empowerment on the racing scene. Cole grew up in Maine, but she sailed at the University of Hawaii, and sailed under the Golden Gate when she competed in the Pacific Cup in 2018. Her frequent video posts of her race have given the sailing world a new window into the world of solo ocean racing, and are surely going to inspire more women to get into sailing at all levels.

After rounding the Horn, Cole is now hoping to find the right breeze to fill her sails and allow her to catch up to race leader Mowgli. Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, president of the International Association of Cape Horners, and Dee Caffari, the first woman to sail solo nonstop around the world in both directions (eastward and westward), both congratulated Cole on her successful rounding of the Cape. Her approach to the legendary cape began with meticulous weather monitoring.

Every rounding of Cape Horn has its challenges — most often too much wind, along with simply finding the right weather window to proceed. Her January rounding of the treachorous Horn was remarkably smooth given the notorious reputation of the Cape. Now, both Cole and Ronnie battle flukier but warmer conditions as they head north.

Farther back, the third American on the course is David Linger on Koloa Maoli, who is currently approaching the Cape with 600 miles to go. He’s played a conservative game to keep his boat and himself safe while making solid, steady progress around the world. Amazingly, all three American racers had their boats in Maine last summer as they prepared to sail to A Coruña for the start.

Of the original 16 starters, three competitors have retired: Juan Merediz and Dafydd Hughes as a result of autopilot issues, and Ari Känsäkoski following his dismasting north of the Crozet Islands.

Like the Three Bridge Fiasco, the Global Solo Challenge is a pursuit-style race with boats having staggered starts, meaning they will place in the order they finish. All three Americans started on October 28. Cole Brauer is currently in second place, Ronnie Simpson in third and David Linger in seventh. Race leader Philippe Delamare is a solid 2600 miles ahead on Mowgli. Regardless, it is impressive to have three Americans participating and exciting to watch Cole Brauer’s outstanding performance as the first American woman nearing completion of a solo round-the-world race.

You can follow the race here.

Winter Open House at Naos Yachts

Latitude’s West Coast Circumnavigators’ List Is Growing

Have you ever thought about how many sailors circumnavigate the globe in their boats? Who they are, what kind of boat they were on, when they sailed? Perhaps you’re even one of those intrepid sailors and are interested in knowing what company you keep.

We recently added more names to our West Coast Circumnavigators’ List and were astounded to see how many there actually are! We lost count somewhere around 300. But that’s not to say there were 300; it could be more, or it could be fewer (though not many fewer). The list includes each circumnavigation a sailor has made, and yes, there are many who’ve been around the Earth more than once, some even more than twice.

Also on the list are those who crewed for a circumnavigation. Clearly not everyone is going to sail around the world alone.

Here are the most recent additions:

Warren Holybee from Port of Petaluma, Morgan 382 Eliana, 2018-2022 (Yes, we were a bit behind on this. Our apologies, Warren.)

Warren tied the knot by sailing into San Francisco Bay on June 5, 2022. He got the cruising bug after taking classes at Modern Sailing in Sausalito in 2014. He began his circumnavigation by doing the 2018 Pacific Cup, and completed his circumnavigation in 2022.

Read about some of Warren’s adventures in the August 2022 issue of Latitude 38.

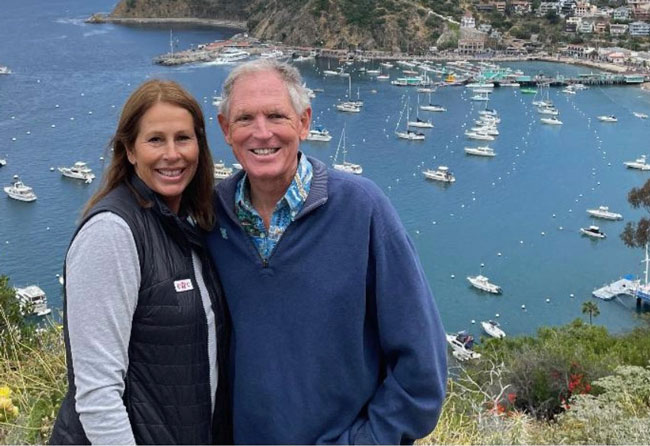

Michael and Barbara Lawler, Newport Beach, North Wind 47 Traveler, 2007-2010 (Again, what can we say? Sorry.)

Michael and Barbara completed a three-year circumnavigation in July 2010, sailing westabout through the Suez and Panama canals. They visited 64 countries on six continents aboard their 1985 Barcelona North Wind 47 Traveler.

“I was on the USC sailing team in college,” Michael reports, “and since then have competed in seven Transpacs and have about 100,000 miles at sea. Barbara has raced in six Transpacs, each time being voted Most Valuable Crew Member. She and I have done five Transpacs together, three on Traveler, including a First to Finish trophy in the Cruising Class in 2019.”

The couple each held a USCG 100-ton license before meeting at the Hawaii Yacht Club following the 2005 Transpac. Plus, Barbara lived aboard a Peterson 44 for five years while cruising the Caribbean.

You can read more about the sailing couple’s circumnavigation in the June 2010 issue.

So we think we’re now up to date, but we’re not opposed to the idea that there are West Coast sailors out there whose circumnavigation we haven’t yet listed.

If you know someone who should be added to the list, please email the details to our Editorial Dept. or send a letter to Latitude 38, Attn: Editorial Dept, 15 Locust Ave., Mill Valley, CA 94941.

For the record, the West Coast Circumnavigators’ List is meant to note boats or people who have

1) left from and returned to US West Coast ports or Hawaii on their circumnavigations; or

2) West Coast- or Hawaii-based sailors who have done circumnavigations starting and ending in non-West Coast ports.

Both skipper and any crew who have completed the whole trip qualify for the list.

The list is intended mainly for cruising boats, but we are happy to note anyone whose circumnavigation was completed during the course of a race. For anyone submitting names for that category, please note the name of the race along with the date(s), and we will include that as part of your listing.

You can support Latitude 38’s commitment to West Coast sailors and sailing news when you click here.

Oakland’s Famous Sailing Watering Hole Quinn’s Lighthouse Closes

We recently heard that the well-known Quinn’s Lighthouse Restaurant & Pub in Embarcadero Cove, along the Oakland Estuary, closed on January 31. The building was an actual lighthouse marking the entrance at the north end of the Oakland Estuary. The lighthouse was built in 1890 and operated until the mid-’60s when it was replaced by an automated beacon. It was purchased and moved to its current location in 1965 and opened as Quinn’s Lighthouse Restaurant & Pub in 1984.

We asked sailor and Master Mariners member Ariane Paul for a few memories. “During the over 20 years that I lived in the S.F. Bay Area,” Ariane said, “I spent many an entertaining evening at Quinn’s Lighthouse Restaurant on the ‘Oakland Riviera.’ It all started when I met Skip and Patty Henderson around 1997 when I joined the Master Mariners Benevolent Association, and Skip invited me to come hear him and his group The Starboard Watch for their regular Thursday night chantey sing at Quinn’s. In the early years, I had to drive over from S.F. and then drag myself to work early the next morning, but then later moving to Alameda, it was a much easier jaunt.”

“Many friendships were made, we all joined in on singing the chanteys. As I also had friends in the marina below Quinn’s, I would often be there on other nights with the regulars playing liar’s dice at the Captains’ Table, which had the names of several memorable regulars who had passed engraved in little plaques around the table. Bill Jansen usually did a water taxi run with chantey regulars on his sloop the Queen of Hearts, coming across the Estuary from Alameda. Sometimes the music would continue late into the night with a second session at Heinold’s First and Last Chance Saloon after Quinn’s had closed for the night.”

“Many of the regulars would occasionally dress like pirates when they came to hear the music. The previous owner of Quinn’s sponsored Skip and Patty’s schooner Aida in the Master Mariners regatta for many years. Sammy was one of the waiters who worked there the entire time I was going to Quinn’s; always welcoming us with a big smile, and one of our favorite people. Sadly, Skip and Patty are no longer with us, and the newer owners shut down the chantey sing during the pandemic. But the friendships forged there and the memories live on.”

Quinn’s Lighthouse was popular with sailors for years and featured a peanut-shell-covered floor, fish and chips, a busy bar, and sailors from the neighboring Embarcadero Cove Marina, the nearby West Marine, the Metropolitan Yacht Club, boat dealers and the British Marine boatyard.

Did you spend time at Quinn’s?

Relax by reading our monthly print publication when you subscribe for yourself or a friend by clicking here.

Westwind Yacht Management — Washing, Waxing and Varnishing

Westwind Yacht Management: Premiere Yacht & Fleet services for the San Francisco Bay Area.