Wednesday Is Hump Day and StFYC Wednesday Night Woodies

Spring sailing has been spectacular. Sailing at all this year is a big step up from this time last year. There’s also been some intense breeze, intense fog, and many brilliant, crisp blue evenings. The St. Francis Yacht Club Wednesday Night Woodies has seen it all. Sean Svendsen mentioned they’d actually done the almost-never thing and canceled two Wednesday evening races because of too much breeze! We stopped by the waterfront last Wednesday, and it was about as perfect as the Bay can dish up. Nice breeze, flat water and perfect evening light.

It’s already Wednesday again and it looks set to be another perfect (don’t jinx it) evening. If you can never get enough of elegant white triangles against a bright green (fading fast) backdrop, the riprap by the St. Francis YC is a great place to find a comfortable rock, pull out the telephoto lens, and enjoy the show. It will be ebbing this evening so the winners will be trying to get close to shore and close to you.

Despite the opportunity to now eat and drink indoors, with the weather willing we can’t think of a better place for some hors d’oeuvres and a drink ‘on the rocks.’ If the evening is warm, open the white; if it’s chilly, open the red.

Delta Ditch Run Dished Out Some of This, Some of That

The Delta Ditch Run race crews reported conflicting forecasts on Saturday morning, but in the end they were all correct. The Richmond Yacht Club race committee started the race right on time, with perfect rolling starts and no over-earlies. This despite light air and the start of a flood current. The racers rode the current and mostly kept their spinnakers full while the light air and heat persisted until the Carquinez Strait. Then a westerly filled in, with nice pressure but not too much.

Until it was too much. In the reachy section between Antioch and Isleton, sailors with instruments reported gusts into the low 30s, with consistent wind in the mid- to high 20s.

In addition to wind-induced mayhem, some boats found mud, sticking for various lengths of time before the rising tide or crew machinations freed the trapped keels. After the stretch past Isleton, the wind eased up gradually. In Stockton it dropped from 20-ish to 10 after sunset. Big-ship traffic in narrow channels added to the challenge.

It was a field day for the Moore 24 fleet. Twenty-six of them entered, and they packed the top of the leaderboard, finishing first through fifth on corrected time. Congratulations to Bart Hackworth and Simon Winer on Gruntled — first overall.

The sixth boat was the recently renovated Santa Cruz classic Nelly Belle, to which we introduced our readers on June 9. (Or reintroduced to the old-timers. Rumor has it she hadn’t raced since 1975!) See all the results here.

Stockton Sailing Club welcomed the sailors with (proverbial) open arms (and an occasional actual elbow bump), commemorative Mt. Gay Rum hats, an outdoor bar, a BBQ dinner, and conviviality on the big lawn along the San Joaquin River.

We’ll have more on the DDR in the July issue of Latitude 38, coming out on June 30. How was your Delta Ditch Run? Feel free to comment below. Please include your full name and the name and type of boat you sailed aboard.

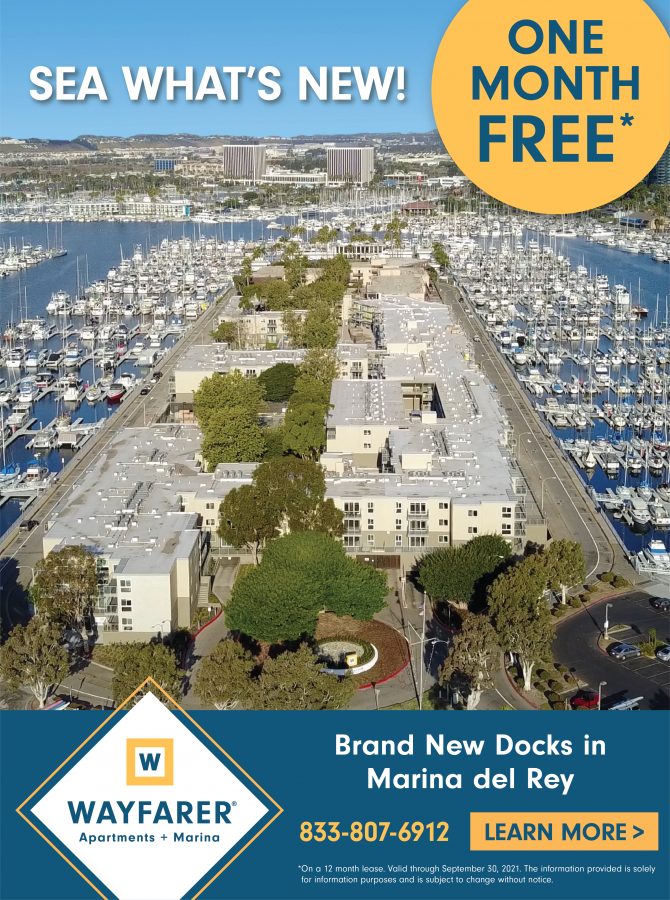

Get One Month Free at Wayfarer Apartments and Marina

Lowering the Mast on a Small Boat with The Resourceful Sailor

I recently lowered the mast on Sampaguita, a Pacific Seacraft Flicka 20 sailboat, for the third time — the first two times in her slip in Seattle, and the last in Port Townsend, WA. It’s a good, low-budget maneuver to know if you own a small sailboat with a deck-stepped mast to effect inspection, maintenance, or emergency repairs, or pass under a low bridge.

Is your boat a good candidate for this maneuver? If it is small enough to put on a trailer, whether or not you do, it probably is. (If you have a trailered sailboat, you likely already do something like this.) The mast of a Flicka weighs 60 pounds and is 26 feet long. Add the standing rigging and hardware, and you might be pushing 100 pounds. Not a daunting weight, but awkward

The tricky part is keeping the mast straight along the centerline of the boat. On a Flicka and many others, this means creating a bridle on each cap shroud to keep tension on the mast as it comes down. I hadn’t figured that out the first time I lowered the mast solo. It threatened to swing over to one side, and upon correcting, swing the other way. There is a lot of momentum at the end of a 26-ft pole, and I feared it would tear the tabernacle right off the cabin top. A dock mate came to the rescue, got the mast under control, and we guided it down the rest of the way without damage.

By the second time, I had discovered The Sailor’s Sketchbook by Bruce Bingham, who, coincidentally, was also the designer of the Flicka 20. One of the many sketches describes how to lower the mast of a boat while on the water. It provided the missing knowledge I needed about creating a bridle to keep tension on the shrouds. It is an easy read and has excellent, entertaining, and easy-to-follow sketches. The Sailor’s Sketchbook is out of print, so you would need to source it from the library, borrow it from a friend, or buy it used.

The key was to seize a stainless steel ring to each cap shroud on the same horizontal plane as the hinge of the tabernacle. All three would act as pivot points. I tied a tight line from each ring to the same-side aft lower stay chainplate, another to the forward lower stay chainplate, and a guyline to the end of the boom. These three lines created opposing forces on the rings, holding them stationary as the mast came down. In turn, this provided enough tension on the cap shrouds to keep the mast centered through the process.

The boom served as a gin pole, a supported pole for lifting, or in this case, lowering, a heavy load. With the main halyard shackle attached to the boom end, there was enough angle and leverage to act as a backstay for the mast. The mainsheet, also secured to the boom end, was an extension of that halyard to the stern rail traveler. The previously mentioned guylines attached to the pivot point rings kept the boom centered during the procedure.

I lowered the mast by removing the aft lower and backstays, leaving the boom/gin-pole system to support it. I loosened the cap shrouds a little and took position in the cockpit. The mainsheet was uncleated, but I kept a secure hold on it. Using the other hand, I pulled on the aft-led headsail downhaul, which ran through a block at the end of the bowsprit and connected to the headsail halyard. Simultaneously, I eased the mainsheet. The masthead pulled forward until gravity took over, and the weight was entirely on the boom/gin-pole system. The bridle kept everything centered, and a controlled lowering of the mast was achieved by simply easing out the mainsheet.

I fashioned cradles for the lowered mast from scrap plywood, foam and carpet, and lashed them to the bow pulpit and stern rail. The bow cradle received the mast as it came down. Once the mast was down, I removed the boom, unpinned the base, and slid it into the aft cradle.

The boom, another part of the puzzle, serves as a gin pole and provides the necessary leverage while lowering and raising the mast. It has guylines connected to the shroud-bridle pivot points, which keep the system centered and triangulated. The main halyard and sheet connect to the boom end, from the masthead and traveler, respectively.

The following video is a first-person view of my third lowering. It does not capture the entire rig, but it does show a controlled descent and how the bridle keeps tension on the mast and boom. I recruited a tall friend whose role was to hold the mast when it just about reached the bottom. (My hatch has a solar vent in it and is an awkward obstruction to work around.) While I can lower the mast myself, it was better with a helping hand. Raising the mast is essentially the opposite action.

If you are interested in trying this procedure for yourself, The Resourceful Sailor strongly encourages you to seek out a copy of The Sailor’s Sketchbook; Bruce Bingham’s instructions are top-notch. It feels good knowing you can lower and raise the mast with the tools onboard. Triple-check that your load points and lines are secure; and it helps to have a confident friend with you. Remember, keep your maneuvers safe and prudent, and have a blast.

South Pacific Entry Update

Since last March, when the COVID pandemic caused French Polynesia and virtually all of its Central South Pacific neighbors to close their borders, many sailors have been thirsty for accurate updated info. But with the ever-evolving nature of government policies and regulations related to COVID, here in Tahiti, as well as in the US and Europe, what’s accurate one day can become dangerously inaccurate the next, resulting in boatloads of misinformation being posted on various online forums.

The bottom line today is that French Polynesia’s maritime borders are still officially closed, but we’re told the doors may finally swing open soon — like, possibly this month — thanks to the lobbying efforts of maritime industry advocates. But today, it’s closed to typical cruisers. (*Please also see “Special Entries into French Polynesia” note below.)

Likewise, French Polynesia’s closest neighbors, the Cook Islands and Tonga, are locked down tight, as they have been for more than a year, with no hints of when they might open. These islands served as the traditional stepping stones for boats en route to Fiji, which is now — sort of — open. (The country recently had a COVID surge, which triggered new quarantine regulations.) But Fiji-bound sailors now face a nonstop 1,800 nm passage from Bora Bora, FP, before making landfall at one of three designated ports of entry. A number of international yachts that had been idling in French Polynesia all year have recently jumped off for Fiji; some of these are New Zealand-flagged or have followed the procedure below.

Some megayachts and a small number of cruising yachts have been granted entry to New Zealand, provided that they agree to spend at least 50,000 NZ dollars (roughly $25,000 USD) for marine services in that island nation during their stay. Meanwhile, we’re told that a marine industry group is lobbying the NZ government to open up to yachts more fully by March 2022. We hope they succeed. However, the fact that New Zealand has no vaccination program may make that date unrealistic. Australia is similarly closed with no opening target yet announced. Also New Caledonia: no one in or out.

*“Special Entries into French Polynesia” — As noted above, French Polynesia remains “officially closed” to international yachts. What has added a great deal of misunderstanding to the situation, however, is that during this period, a number of foreign-flag vessels have been granted short stays based on special needs or circumstances, and at least a few have even been granted stays of a previously normal length. Special entry requests are handled by the FP maritime agency DPAM. Applications are reviewed individually, but I am told that all such requests must demonstrate what is termed “imperative need:” special circumstances that deserve special consideration.

Who Joins the Pacific Puddle Jump?

Since its inauguration in 1997, the PPJ has always been promoted as a loosely structured passagemaking event between various points along the West Coast and French Polynesia. It imposes a minimum of rules and requirements on entrants, and is focused on fleet camaraderie and safety. But it is certainly not intended to be a hand-holding event.

Of the hundreds of international sailors who have done the Pacific Puddle Jump, many previously had substantial bluewater experience, including circumnavigations. Some wanted us to know that they were normally fiercely independent, and not the sort who normally join rallies. Yet they signed up anyway to meet like-minded cruisers and be part of what we like to call the ‘annual westward migration’ to Tahiti and her sister islands.

Again, if French Polynesia reopens in the coming weeks, as anticipated, we intend to announce the 2022 Pacific Puddle Jump by midsummer.

Passage Nautical Is Seeking an Independent Contracting Commissioning Agent

Passage Nautical is seeking a skilled and experienced Independent Contracting Commissioning Agent!

Duties include both power and sail boat projects, electrical work, rigging, minor engine service for IB and OB. Knowledge of 12V and 110V systems, battery systems, and plumbing systems.

Must be able to work independently and follow technical instructions as required. Please send resume to [email protected]

To learn more about our company go to: https://passagenautical.com/