Why Does the US Rescue Sailors for Free? Because We Can

Who should pay for rescues on the high seas?

We asked that very question in January, though the query arises — or erupts, like an angry volcano — in the case of nearly every rescue or incident of “questionable” judgment. There are countless variations, but at the core, the questions boil down to: “Why are my taxes funding this?” And, “Why doesn’t the rescued mariner have to pay something?”

“The question of where to draw the line between the freedom of the high seas and personal responsibility is difficult,” a reader commented on the high-profile rescue of a kayaker off San Francisco in June 2021. “New Zealand draws it at one end of the spectrum and the US draws it at the other end.

“Why, at a minimum, should there not be an inquiry done by the Coast Guard for every significant rescue? If the inquiry found the ‘mariner’ did not heed the basic rules of seamanship of being a capable crew on a seaworthy boat, why should they not be accountable for some or all the costs of the rescue? If mariners knew there could be an accounting of their actions they might think twice or come up with a private rescue plan. That would be a good article for Lat 38.”

We sought to investigate that angle, but were wary of the knee-jerk reactions that tend to come with every rescue. Besides, the answer became almost absurdly self-evident.

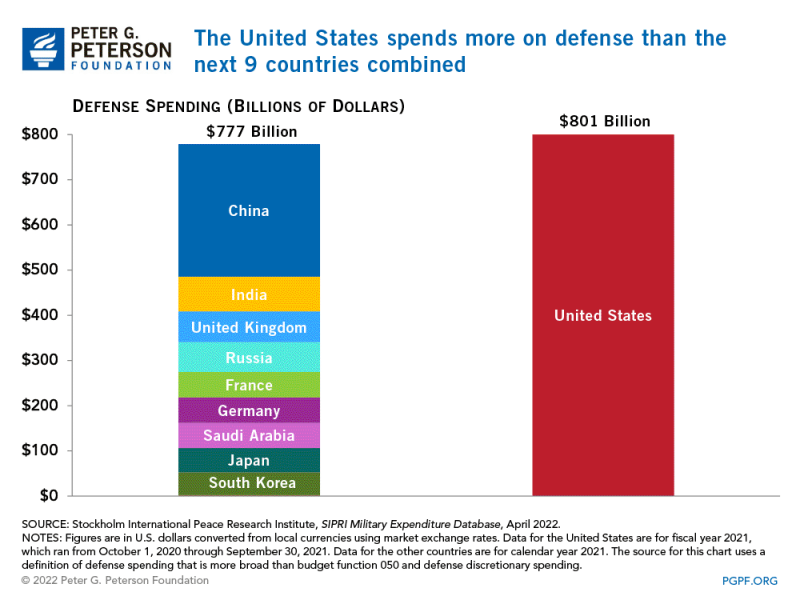

Why do we rescue sailors for free? Because we can, because the United States spends more than 10% of its federal budget, and nearly half of its discretionary spending, on the military, and one of the apparent benefits of this staggering investment is the humanitarian component. We have bought and paid for the most elite ocean-patrolling force in the world; we have invested in the infrastructure and personnel to carry out rescues on the ocean.

The glaring self-evidence revealed itself to us during the rescue of Andy Schwenk in August, which was a joint effort of the US Coast Guard, the California Air National Guard, the Air Force, a commercial ship, the Pacific Cup organization, and another sailing vessel. The military assets used to rescue Andy were two Pave Hawk helicopters and two C-130 airplanes, one of which dropped two pararescue troopers/medics, or PJs, to rendezvous with Andy on the commercial ship.

“I kept apologizing to the PJs for the trouble,” Schwenk told us, referring to the two medics who parachuted from a C-130 to the Taiwanese tanker to care for Schwenk before the trio was picked up by a Pave Hawk helicopter. “They kept telling me that they were happy to be there, and that it beat fighting wildfires.”

Some of us here at Latitude are less than enthusiastic when Fleet Week comes rolling through town. We fully support members of the military and their families (one of our staff used to teach sailing for the Navy), and feel nothing but gratitude for the people who risk their lives to save sailors, but we’re wary of the policymakers wielding this awesome force with its immense budget.

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” said President Dwight Eisenhower in 1961. “The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists, and will persist. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.”

For peaceniks like us, using the armed services for humanitarian purposes is a kind of consolation prize for what we see as dramatic imbalance in our national fiscal priorities.

So, are we saying, “Throw caution to the wind and head out to sea with no training, poor equipment, and ambitions in excess of your skills? What the hell? Someone will come to rescue you, gratis. Tell them that Latitude sent you.”

We are absolutely not saying that.

We cannot emphasize safety and training enough, nor can we easily quantify those concepts. Surely, the first part of seamanship is learning your own boundaries — meaning your strengths and weaknesses — and planning and training accordingly. A reader mentioned earlier wondered what if “‘mariner[s] did not heed the basic rules of seamanship of being a capable crew on a seaworthy boat”?

There are some objective measures for seamanship and seaworthy vessels, but there is no universal standard or licensing, or any guarantee that this would prevent mishaps at sea. We have said this many times before: We’ve seen novice sailors go on to circumnavigate without incident, and we’ve seen seasoned and endlessly qualified mariners get into trouble.

(After the strange rescue of the Sea Nymph in 2017, where two apparent sailing novices had been adrift in the Pacific for months, one reader wrote us, saying, “Our completely voluntary, recreational sport [is] largely unregulated, and I wish to keep it that way. It is my take that regulations/authorities appear as a reaction to abuse/excess/problems.)

It is only natural, and at times beneficial, to consider the “lessons learned” after any incident at sea, even one that we’ve only read about and therefore have little knowledge of. There’s a fine line, however, between an objective look at someone else’s decisions, and armchair captaining, or flagrant judgment of sailors doing their best to cope with a situation.

There seems to be a need to punish or even shame sailors for their mistakes, and to point to the tax dollars used for their rescue as the most egregious evidence of their transgressions. (Has this “shaming culture” taken a more bitter tone and become more of a knee-jerk reaction in the social-media era?)

We often hear people say, “I don’t want my tax dollars to pay for this.” If there is an option of opting out of paying for the services or policies that you do don’t like, sign us up! And, if you’re really concerned about the money, then there are lots of corporations that pay little to no taxes.

And if you’re worried about the people doing the rescuing: “This is what we do,” said a Bay Area-based Coast Guard officer about the rescue of kayaker Cyril Derreumaux in 2021. “We’re budgeted for it. Because of the volume of cases we do here, we’re probably the best in the world at it.”

I’ve spoken with S. A. R. leaders more than a few times. Their refrain is consistent. “if there were risk of financial fine/payment for the very large cost of our rescue operations we worry that people will wait longer, until things are worse and we are less likely to make a successful rescue or put our heroes in even more risk.” Your points about the military industrial complex are on target. We are unlikely, with so many bad actors in the world, to make progress on shaking loose from its grip anytime soon; in the meantime, hail to the USCG, yes, military, but mostly with a peaceful mission.

In forty plus years of sailing, and boating, we have had nothing but positive interactions with the US Coast Guard. We heard the VHF16 call 2/7/22. “All vessels in vicinity requested to keep a look out and assist if possible”. A fisherman had gone in the water off Muir Beach overlook. We were getting our crab gear wet a few miles off shore, so we responded. Retrieved our gear, burned our own fuel. Stayed in the search for a couple of hours until we started to run out of daylight. The USCG had a helicopter, and a 40-50ft MLB, engaged in the rescue effort, but what impressed me most was the jet ski teams. They were just right there in the surf between the rocks and jagged coast line. Let me tell you, those men earn their money! Now we can talk about how the fisherman got in the water, in the first place, and we can cry about tax dollars, but if it was my friend in the water that is the response I would hope would be there. My plan is to be part of the rescue attempt, and not the one needing rescue. A superior captain (to me) is one who uses his superior judgement to stay out of situations requiring his superior skills. In my opinion the USCG is worth every freaking penny they get and really should get MORE tax dollars. I understand non-boaters who feel the money should go to schools instead, and non parents who resent tax dollars spent on education. I understand non-scientists who think the cubic dollars spent on space exploration is a colossal waste of tax moneys, and wealthy folks that do not understand why “entitlements” (I paid into my entire working life) are important to honor. My experience, of 63 years, is the people who do not want to pay for services are also the loudest voices complaining when a service they need is not properly equipped, or funded. Lets work on Government accountability, and transparency. I am a full believer that we can do better. Vote better. demand better from our representatives. But seriously “defund the Coast Guard”.???

Sea rescues are good practice for the forces involved, and the skills honed in doing so can and will be used in saving their own personnel in other instances. Also, if there were no budget for sea rescues of civilians, the savings would probably be, at least somewhat, offset by an increased training budgets. All of this is in addition to the value that we, as Americans, put on human life.

Back in the 1970s the USCG could terminate a “manifestly unsafe voyage” after determining the vessel couldn’t make the proposed voyage. Judgement was not based on the sailors’ lack of skill. Regarding assistance to mariners in ill health, currently one particular case looms large before the local YACHTING public. Perhaps that case should be considered along with the assistance provided all merchant ships and fishing vessels.

The US military gets involved with SAR activities world-wide. Here’s a link to a story about a B-52 that located a sailing canoe that had been lost for a week in the Guam area..

https://theaviationist.com/2018/07/03/b-52h-crew-from-guam-locates-ocean-canoe-crew-gone-adrift-in-pacific-in-a-rare-bomber-maritime-sar-mission/

In a Dramatic Open Ocean Search an Air Force Crew Finds Paddlers Missing Six Days. The lost canoe was located by the crew from one of the B-52H after it was compared to a similar one that appeared in a Disney cartoon.

Good analysis Latitude.

Appreciate your perspective.

Excellent point about how we (the US) spends more on defense) war than that nice 9 countries combined.

This strikes me as most unfortunate… think of the things we could do about the climate crisis, health care, education, homelessness, etc etc if we scaled spending money on war back by 50%!

Totally agree, thank you for your well balanced and thought out response.

I recall reading someplace that military and USCG SAR assets viewed civilian rescues as good practice for wartime and the battlefield ( I think another reader echoed this in their comment also ) . Makes sense..

Practice makes perfect!