Max Ebb on Docking: Walk the Walk

In April’s Latitude 38, Max Ebb, Lee Helm, and a retired pilot discuss prop walk after Max gets some help docking a friend’s boat.

“Docking a big boat is all about confidence.” Those words came to mind as I maneuvered my friend’s boat toward its slip. It was twice the size and five times the weight of my own boat, and I had volunteered to move it back to its marina berth from the boatyard while the owner was out of town.

This was a single-finger berth, port-side-to, and there was some wind blowing away from the dock. A little bit of extra speed would be required on the final approach, to minimize the effect of the wind. “No problem,” I thought to myself. “I’ll hit reverse at the right time, and the prop walk will pull the stern to port.”

A voice in my head asked me to practice reverse thrust out in the fairway, but confidence overruled and the voice was ignored. I should have listened. The approach into the slip went exactly as planned, but when I applied power in reverse, the stern swung to starboard, not port, and the wind was blowing me against the neighbor to leeward, a large powerboat, with no room for backing and filling. Naturally, I had not put out any fenders to starboard.

Fortunately, the boat to starboard was a liveaboard, and the owner appeared on deck just in time to help me fend off. Other onlookers ran to help, and it wasn’t long before my friend’s big yacht was safely pulled up against the port-side finger.

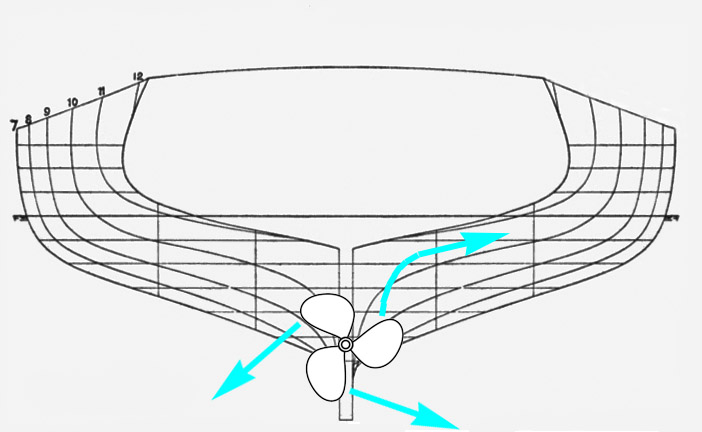

“Must be a left-handed prop,” deduced the liveaboard skipper to starboard after I explained what had gone wrong with my docking attempt. “Sure felt like it,” I agreed. “I expected the prop walk to pull the stern to port, like it usually does.”

“Not with a lefty propeller,” he said. “It’s all about torque and P-factor. Ask any pilot.”

“I understand torque,” I said. “But what is this P-factor?”

“Ask any pilot,” he repeated. “And I just happen to have logged a couple of thousand hours.”

He didn’t wait for me to ask but launched into asymmetrical flight dynamics 101.

“P-factor is when one side of the propeller is producing more thrust than the other side,” he began. “Think of a powerful single-engine plane with a big propeller. Especially a taildragger. The plane starts the ground roll with a high angle of attack. The propeller shaft is nowhere near parallel to the incoming air flow, so the blades on the starboard side of the plane, going down and partly into the incoming flow, see more wind and more angle of attack than the blades on the port side of the plane going up. That puts more thrust on the right side than the left, so you have to push down hard on the right rudder pedal just to stay lined up with the runway. After liftoff, during climb, the angle of attack is still higher than in level flight, so you still have that unbalanced thrust trying to make the plane turn left, and you have to keep pressure on the right rudder.

Continue reading at Latitude38.com, or go pick up a magazine.