Mexican Tall Ship Hits Brooklyn Bridge Leaving Two Dead

On Saturday, May 17, at about 8:30 p.m. New York time, the Mexican tall ship Cuauhtémoc drifted backward under the Brooklyn Bridge, snapping off all three of her topmasts and killing two crew, including a 20-year-old female cadet. Twenty-two other people were injured, about half of them critically. Some 277 crew and cadets were aboard at the time.

The ship was departing New York after a goodwill visit when the accident happened. As with many tall ship visits to ports all over the world, she was festooned with flags and lights, and with crew stationed on the yardarms.

According to reports, the cause of the accident was a loss of engine power shortly after Cuauhtémoc pulled away from Pier 17 in Manhattan. The current in the East River then drove the ship backward under the bridge, breaking off her topmasts sequentially from mizzen to foremast.

The accident was videotaped by dozens of cell phones from shore and from the bridge. It’s literally everywhere online and was the lead story on almost every TV newscast over the weekend.

The ship’s next stop was to be Iceland, but she will remain in New York until the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) completes their investigation. The Mexican navy, which owns and operates the ship, has pledged full cooperation and transparency, and is conducting its own internal review in coordination with US authorities.

As you might imagine, speculation is rampant over this incident, with most commentary centered on the actions, and perceived inaction, of the captain, pilot, and a tugboat that appeared to be right alongside the ship. We’ll let you know what the NTSB report says when it’s released.

Cuauhtémoc — known as the “Ambassador and Knight of the Seas,” and named for the last Aztec emperor to fight against the Spanish — was built as a cadet-training and goodwill ambassador ship in Spain in 1981–82. She is 296-ft (sparred length) long, 39-ft in beam, and displaces 1,800 tons. Her tallest masts are 147 feet.

In the 43 years since, she has sailed over 400,000 miles, visiting ports all over the world, including San Francisco in 2005 and 2009. According to abc57, the ship was on its training tour for the graduating class of 2025.

Numerous videos and photos of the incident are circling the internet. The two below show the tragedy unfolding from different angles. Warning: The scenes may be distressing to some readers.

Our condolences go to the captain and crew of Cuauhtémoc and their families.

‘Wild Spirit’ — Cruising West Coast Waters Since 1978

All sailboats have a history, no matter how brief. But when we discover a sailboat with a history we know about, it’s fun to connect the dots and learn where the boat is now, and perhaps where it’s been. In the case of Wild Spirit — designed by Tom Wylie, built by C&B Marine of Soquel, CA, and launched in 1978 — we recently heard from her current owners, Larry Vito and Kait Reid. It appears that Wild Spirit now spends much of her time cruising in Mexico.

Wild Spirit is a Wylie 36, a custom cold-molded cruising cutter designed and built for Sausalito sailmaker Peter Sutter. In November 1978, we published an interview with Peter in which he told the story of how Wild Spirit came into existence. The boat was the result of a discussion shared among Peter, Tom Wylie, Dave Wahle, and Skip Allan about their ideal cruising boat. They all came up with almost the same designs.

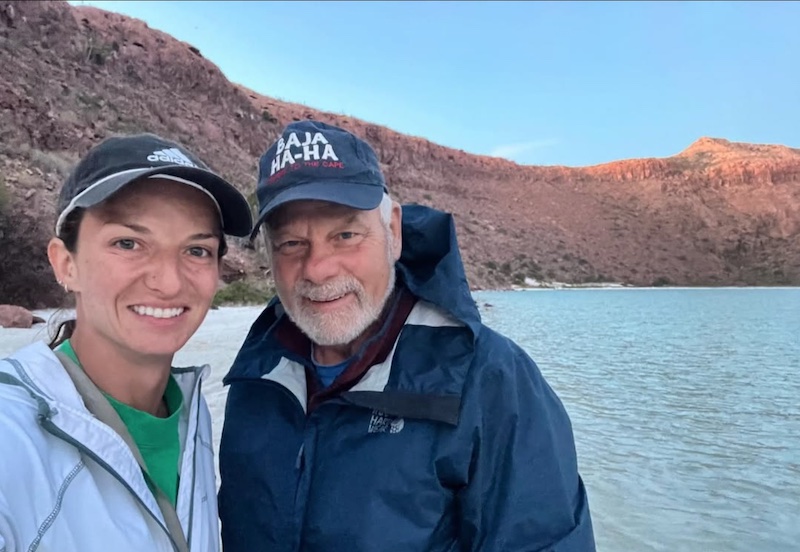

We’re still missing 35 years of Wild Spirit‘s life, but we do know that Larry has been her caretaker for the past 12 years. During that time she has sailed to Mexico with the Baja Ha-Ha, at least once. She was among the fleet of 168 registered boats in 2018. In 2023, Larry and Kait started an Instagram account for their cruising adventures aboard Wild Spirit, though it appears the cruising couple have been too busy enjoying life to get bogged down with social media, and we heartily approve.

At this time, or at least as of early May, Larry and Kait are “bouncing between cruising in Sea of Cortez, Mexico, in the winter” and adventuring in their camper van over the summer — this year heading to Alaska.

If you know where and with whom Wild Spirit spent her time between Peter and Larry’s ownership, we’d love to hear from you.

In the meantime, you can read the interview with Peter Sutter in the November ’78 issue of Latitude 38.

Visit Antioch Marina, the Gateway to the Delta

The View From the Bowsprit of a Bay Area Foiling Cat

Ross Stein was out sailing on the Bay recently and sent us this cool shot of the on-water action.

Here’s a GoPro photo from the tip of our bowsprit on a Flying Phantom Essentiel, an 18-ft foiling catamaran, taken last month with Henry van den Bedem on the trapeze while I drove.

On a foiling cat, one flits between joy and terror in an instant. The sensation of foiling is addictive, floating over the chop and boat wakes that would otherwise pummel a small boat. The crew is constantly moving fore and aft on the wire to keep the platform flat. But the capsizes — both to weather and to leeward — wake you out of your reverie.

Once foiling, the boat is displacing just a gallon or so of water, and so it has no inertia, becoming super-sensitive to the helm. Move the tiller just a few inches and you tack or jibe, so you grip the tiller for dear life.

The modern-day hang 10, or perhaps 20?

Max Ebb — It Starts Here

“Three … two … one …,” Lee counted down to the start signal. “Bang!” But her “bang!” was followed by an awkward second of silence before the horn sounded from the RC boat.

“Amateur RC,” Lee sighed. “But like, it’s just a beer can race; you can’t expect pro-quality timing.”

The important thing was that I had nailed a boat-end start, at the right end of the line. Our bow was just inches from the limit mark at the horn. Lee Helm would not normally hop onto my boat for a weeknight club race. But the wind was too light for her foiling windsurfer, and she arrived at the club guest dock a little too late for a ride on a faster boat.

“Like, don’t try that kind of start in a competitive fleet,” she advised me. “You had the boat end all to yourself.”

“Yes,” I said. “I like the starboard end of the line, even if the pin end is slightly favored. It’s just easier to time it right when you can see both starting marks on approach, and there’s also much less doubt about being over early at the gun. Give me another couple of clicks on the jib sheet, please.”

“Racing in a big one-design fleet will cure you of that,” Lee suggested as she cranked the winch handle half a turn.

As she did that my mainsail trimmer gave me a little more backstay and more sheet tension to flatten the main. We were pointing high, going fast, and the boats that followed us across the line were in very bad air.

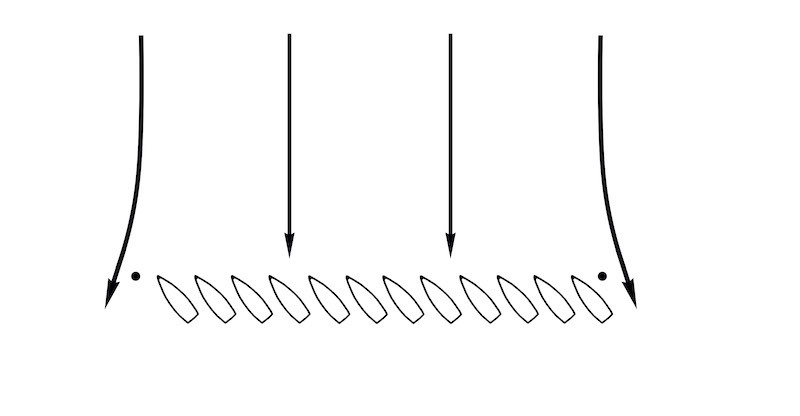

“Even with a square line, exactly at right angles to the wind,” said the main trimmer. “I usually prefer the pin at the left end. It doesn’t show up in the pre-start wind checks, but when there’s a crowd of boats at the starting line, the wind tends to be blocked a little and flows around the fleet as if it were one solid obstruction. You get a starboard tack lift at the pin, and a header at the boat end. Not a big effect, but it’s there.”

I had seen that diagram drawn on several yacht club bar napkins. So had Lee, and not surprisingly, she had to point out why it was wrong.

Westwind Yacht Management — Washing, Waxing and Varnishing

Westwind Yacht Management: Premiere Yacht & Fleet services for the San Francisco Bay Area.