Arriving on Strange, Empty Shores in a Foreign Land

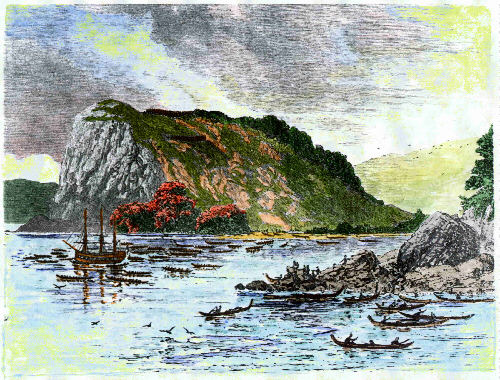

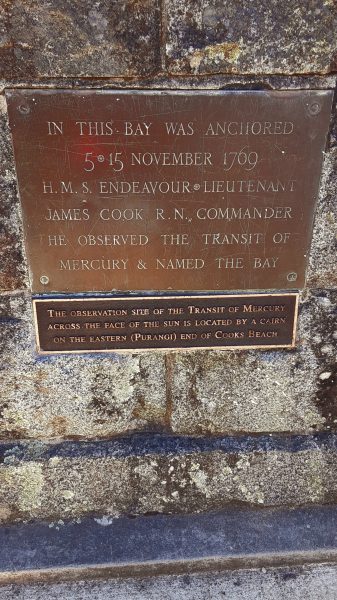

In November 1769, the HMS Endeavour, under the command of Captain James Cook, sailed into Maramaratotara Bay, New Zealand, to observe yet another rare astronomical event. Nearly half a year earlier in Tahiti, Cook and his crew had documented the once-in-a-century transit of Venus across the face of the sun. Now in New Zealand, the Endeavour’s astronomers observed Mercury taking the same path.

Cosmological missions aside, one cannot help wondering what it was like for Cook and these sailors, who were the astronauts of their day, to arrive on such strange shores. Was it equivalent to ‘beaming’ down to another planet? Or, was it all just another coast, another beach, another strange and foreign land?

On March 24, my captain and I pulled into the Whitianga Harbour, a port town on the east cost of New Zealand’s North Island. As we approached shore, the natives were bashful. The natives were, in fact, nowhere to be seen. The abundant waterfront pubs were shuttered, dark and empty, and Whitianga was a ghost town. New Zealand was roughly one day into its national lockdown to combat the spread of COVID-19. (Just a few days before, I’d seen an internet meme that read, “I was expecting zombies for the apocalypse. This virus sucks.” Who knew that the end of the world would be marked not by roving bands of marauding pirates, but rather, by a recalcitrant citizenry hoarding toilet paper and Purell?)

Regardless of the state of the world, we were in need of provisions, fuel and water. The marina told us that we could tie up for no more than two hours, but that we were obliged to depart immediately thereafter. (The guidelines governing foreign cruisers traveling in NZ were still evolving, and there was far more gray area than certainty.) Once fueled up, we plotted a course through the dark, quiet waterfront town in search of the grocery store. Over the next few weeks in New Zealand, we would find that big supermarkets observe varying levels of strictness enforced on shoppers. In Whitianga, we found bored teenagers who hadn’t seemed to get the memo that the world was ending.

But surprisingly, we stumbled onto Cook’s footsteps . . .

Given the end-of-the-world vibes, we saw fit to enjoy a cold libation while walking the half mile back from grocery store to boat. I would later cheers the crew of the Endeavour, who were absolutely hammered while they sailed the seven seas and discovered strange, new lands. “The Endeavour sailed with a staggering quantity of booze,” wrote wrote Tony Horwitz in Blue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before. “Twelve hundred gallons of beer, 1,600 gallons of spirits (brandy, arrack, rum) and 3,032 gallons of wine. The customary ration for a sailor was a gallon of beer a day, or a pint of spirits, diluted with water to make a twice-daily dose of ‘grog.'”

After taking on water, we left the visitors’ dock around 9 p.m. and motored for about 30 minutes to our anchorage. One of the many magical moments afforded by cruising is dropping anchor in the night, and waking up to the sublime.

As I mentioned in Part 1 of this series, I was not trying to follow in the footsteps of Cook, as Horwitz had so meticulously done. Rather, I was accidentally stumbling on a path that was fading in the sand. Because in New Zealand, Captain James Cook is always around the corner.

I found that the sand rimming the Shakespeare Cliffs was, of course, Cook’s Beach. Paddling there from the boat, I was worried that the exceedingly charming Kiwi authorities might politely reprimand me for leaving my vessel. At this point, it wasn’t clear what was considered ‘lawful’ exercise or activity. (It’s still a little murky.)

Living with plague also felt reminiscent of the 18th century. Captain Cook might have been quite at home in our modern-day pandemic, having hailed from a time when disease consistently ravaged the world, and ultimately decimated nearly every “foreign land” the Endeavour visited — as well as Cook’s crew. Stopping in for repairs in Batavia, Indonesia (now Jakarta, where I used to work at an English-language newspaper), the Endeavour’s previously-healthy sailors quickly fell ill. “Batavia’s ubiquitous canals, which doubled as sewers and dumping grounds for dead animals, formed stagnant breeding grounds for mosquitoes and disease,” Horwitz wrote. (I can attest to Jakarta’s inexplicable thoroughfares of still water.) Ships arriving from all over the world brought illnesses of their own.”

Sorry . . . where was I?

Hiking to the top of the cliffs, I was surprised — and not at all surprised — to find Cook.

Keeping up his reputation as the naming-est sailor to travel the oceans, Cook renamed Maramaratotara Bay for the planet that was in his crosshairs. (I’ve also found information that says Mercury Bay’s original name was Te Whanganui o Hei Bay.)

Granted, the idea of ‘naming’ that which has already been named and long inhabited is a tad controversial. But that’s a topic for another time.

Stay tuned for the conclusion of The Book that got Me Hooked on Cook, coming soon.

Seems like everywhere we go in the South Pacific we feel Cook’s presence. How did he do it without a diesel engine or watermaker?

I once read the official biography of Cook. It is a lengthy tome, but well worth it if you have the time and interest.

With that much booze it is unlikely anyone went thirsty. The nicety of taking a bath/shower is a modern phenomenon. Must have been a little sour in the bunks.