Lucie on the Move

An 89-year-old lady recently won New York Yacht Club’s Annual Regatta in Newport, RI. The lady in question, the Classic Six Metre Lucie, was skippered by Craig Healy, a dentist from Tiburon. The regatta, held on June 14-16, pitted Lucie against three other Six Metres, a pair of Luders 24s, and a Herreshoff R 40.

John Burnham, who holds multiple IOD World Championship titles, writes the blogs for Lucie and Dorade. He reported that, in the two days of around-the-buoys racing, the other Six Metres were not a factor due to breakdowns and retirements.“Gamecock won a pair of races, but Lucie was second each time, and the resulting 1-1-2-1-2 scoreline was decisive in favor of Lucie.”

Lucie and Scoundrel

In mid-July, Craig Healy skippered Matt Brooks’ and Pam Levy’s Scoundrel, another Six Metre, in NYYC’s 175th Anniversary Regatta (they placed second in their division). But Scoundrel and Lucie are not sisterships. Craig explains: “The Six Metre rule is pretty straightforward. You plug in the various parameters of the boat — the length, the waterline, the sail area and so on. It’s basically a mathematical formula. If, at the end you get 6.00 meters or less, you have a Six Metre. The boats typically tend to be long and skinny and heavy. Say, 34 feet long, 6 feet wide, minimum beam 2 meters, and they weigh maybe 8,000 pounds.

“As the years have gone by, like anything in yacht design, improvements have been made even though the rule hasn’t changed. Advances have been made in yacht design and hydrodynamics. The biggest change in the meter boats was the wing keel. So, think ’87 America’s Cup: Australia beats United States with the wing-keel boat Australia II. That revolutionized meter boat design. You could invert the keel. In this case the wing keel has a very short root that attaches to the hull. It becomes very thick and longer as you go down. So the center of gravity is very low, and the wetted surface is actually less. To finish it off, wings were added down low extending off the keel. That adds a lot of extra lift.

“Lucie has just a traditional keel. The rudder is attached to the back of the keel. Whereas Scoundrel has a wing keel attachment and a spade rudder in the back. It’s very, very efficient, much faster. Even though both are ‘Six Metres’.”

Six Metre Class Divisions

When they have major championships, the Six Metre Class divides the boats into Classic and Modern (or Open) divisions. ‘Modern’ boats were built from 1966 to today. “Classics would be before that. Most of the Classics were built in the ’30s. There was a big boom in Six Metres after the Depression, as opposed to things like J Class boats. Wealthy people who sailed weren’t so wealthy, so there were a lot of Six Metres built then, followed by a period of dormancy.” Scoundrel was built in 1989.

The Nevins Boat Yard in the Bronx built Lucie in 1930 for Briggs Cunningham. “It was for his wife Lucie, who the boat is named for. (Briggs Cunningham invented the cunningham, as in the mainsail adjustment.) Matt Brooks and Pam Levy have kept Lucie in pristine condition, having restored it back in 2011. It has a wooden mast, wooden boom, wooden spinnaker pole, and truly Dacron sails — not modern ‘dacron’ that’s not really Dacron. There are not many boats in the class that are kept in that original condition, maybe like five or six.”

Lucie now lives on a trailer in Bristol, RI. Jens Lange takes care of her at his boat shop, Baltic Boat Works. “Jens is in charge of the maintenance and any improvements to the boat. He does a great job,” said Craig.

To Finland

Just today, Lucie arrived in Hanko, Finland, for the Six Metre Worlds. “After we raced, Jens took it back to Bristol, just a short tow from Newport, hauled the boat out of the water, and derigged it. The boat is delayed in shipping,” reported Craig on Monday. “Our original plan was three days of practice followed by two days of Pre-World Championship Regatta on Saturday and Sunday, followed by the world championships. The best-laid plans have been foiled by shipping snafus. We’ll focus on rigging and measurement, with a possibility of sailing on Saturday. The Worlds begin on Monday. We’re kind of getting thrown right into the regatta, even though we had all these wonderful plans, super well-prepared.”

The crew flew out Monday night, arrived Tuesday, and were planning to sail on Wednesday. “Now we’ll be fortunate to sail Saturday. We’ll make the best of it, that’s for sure. We’re all resilient people.”

Onde Amo’s Sad Story

“Here’s how we ended our Transpac this year: Less than 188 miles to Diamond Head, we were forced to retire,” says Don Ford, trimmer aboard Stephen Ashley’s Shoreline Yacht Club-flagged Beneteau First 40.7 Onde Amo.

Skipper Stephen Ashley reported in the boat’s blog: “On Monday, July 22, around midday, and looking at a midday finish on Tuesday, I heard the words that I have come to hate: ‘I have no helm!'” Watch captain Debbie Kraemer and Ashley were just starting to repair the A2 (again). It had come apart the evening before after they had flown it most of the day. “The repair that we did before worked so well that it came apart at a different spot!

“Not suspecting a major failure like a missing rudder, I dove into the aft compartment to check the steering linkage,” continues Ashley. “All seemed to be in order.” At the wheel, Mike Arrajj could turn the helm and the steering quadrant responded as it should. Peter Shumar grabbed a pair of fins, tied a line to keep him attached to the boat, and went over the side to take a look. There was no rudder! “As Peter described it, he was counting appendages hanging down from the bottom of the boat: 1) keel, 2) sail drive, 3) hmmmm. OK, one more time: 1) keel, 2) sail drive, 3) hmmmm. It was now clear that Onde Amo’s rudder was lying at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean in roughly 8,500 feet of water. I tried to get Peter to go look for it, but no luck.

“We deployed the emergency rudder, a rather heavy, clumsy stainless-steel contraption that took me almost an hour of swearing to deploy in the slip for our safety inspection. With several sets of interested hands, we were able to deploy it quicker than I imagined possible on the open ocean. While it was better than no rudder at all (the other option), it is not the easiest to use to control the boat. The blade of the emergency rudder (the part that sticks down in the water and actually steers the boat) is less than half the size of our regular rudder and has a much smaller range of motion. It is controlled by moving a stainless-steel pipe back and forth.”

The crew notified the race committee, the Coast Guard and Ashley’s fiancée by satphone of their situation. They doused their headsail (the #2 jib) to see if they could sail the boat with just the main up. “It worked for a while, but as the wind built, it became less stable, so we took the main down and sailed for a while with the #2 jib alone. This was manageable, but again, as the wind built, this became a challenge. Finally, we had to drop all our sails and turn on the engine for propulsion. At that point, we had to retire from the race. If you use your engine for propulsion, it is a rule violation. You can use your engine to charge the batteries, but not to push the boat.

“We contacted Boat US to see about a tow to Honolulu. Boat US is the ‘AAA of the ocean’. As we were still 150+ nautical miles from Honolulu, it was suggested that we head for Molokai instead, as it was less than 100 nm away. There is a fisherman on Molokai that contracts with Boat US to do towing. Therefore, we headed for the channel between Maui and Molokai making the channel on the morning of Tuesday, July 23. Our plan was to get into Molokai, fuel up so we would have enough to motor all the way to Honolulu if we had to, and then catch up with Dedric Manaba for our tow the last 50 miles or so across the famed Molokai Channel (the channel between Molokai and Oahu).

“As we were motoring along the southern side of Molokai, the wind built to the point where we were seeing gusts of 35+, which made steering the boat a real challenge. Dedric informed us that there were Small Craft Advisories and that we should spend the night in Molokai and leave early the next morning to be towed to Honolulu. Although we were all ready to get into Honolulu, we opted once again for safety and settled into the tiny harbor at Kaunakakai. It was an interesting experience, as the wind was blowing 35 and we only ran aground three times trying to get into the two areas where they wanted us to dock for the night. We ended up getting part of our port quarter up to the end of the dock so we could at least get on and off the boat. We were able to get showers, walk into town for a cold beer and some groceries, and pizza for dinner.”

“We started out at 3 the next morning as the winds had laid down and Dedric wanted to get us to Honolulu and return to Molokai in the same day. The ride across the channel under tow behind his fishing boat was relatively uneventful, although the waves in the Molokai Channel did make it interesting to try and stay behind his boat. He was able to get us into Ala Wai Harbor where he turned us loose to meet our welcoming committee.

“We were still able to get our ‘Transpac welcome’ under our own power, and we were also able to get into our slip with the emergency rudder, almost by ourselves. I think we made the crew of Bolt nervous (they were in the slip next to us), so they were more than happy to assist with our landing. We had finally traversed the 2,250 miles of ocean between Long Beach and Honolulu in 14 days, almost to the minute. There is no official record of our time.”

“Onde Amo sits in Ala Wai Harbor waiting for a shipping trailer to be sent over from San Diego so we can ship her home on one of the Pasha ships. As this was not our original plan for getting her home, it will be approximately six weeks before she will once again be a SoCal girl and we can commence the process of fixing all of her booboos, like a missing rudder and a spinnaker still wrapped around the headstay.

“Our team took every challenge that the race threw at us and kept going. Yacht racing has been described as one of the few sports where the playing field is changing under you as you compete. It certainly was for the crew of Onde Amo.”

Vallejo Boat Works Is Hiring

Finding the Golden Gate

Recently I was given the opportunity to sail from Santa Cruz to Sausalito aboard Call of the Sea’s schooner Seaward. The 82-ft vessel had just completed a five-day educational camp and would be returning to the Bay Area in one leg. Was I excited? You bet. I had never sailed outside the Gate and immediately lapsed into a daydream of clear skies, fair winds and following seas with pods of whales and dolphins forming the backdrop to my utopian day on the water — I had seen the photos!

The reality was as removed from my image as night is from day. The morning of our departure held wet decks, gray skies and not a breath of wind. Not to be deterred, I accepted this as normal weather ahead of the offshore breeze that would clear the fog bank and reveal the beauty of the Pacific Ocean. However, four hours and two watches later, I came to accept that rather than the voyage of my dreams this would be an exercise in patience and observation. The skies did not clear; the lack of wind and the rolling swell meant the only canvas visible was a limp main-staysail, and the only creatures that broke the still surface of the oily-looking water were seabirds and a small rookery of playful seals.

The crew were no doubt relieved to have nothing to do but ensure the boat stayed on course as we motored along at around 7 knots. After a week spent educating and entertaining curious teenagers, they quickly relaxed into a schedule of sleeping, eating and creative pursuits. One crewmember even practiced scrimshaw on a bone she had found at the beach. The helmsman completed the seafaring picture singing sailing songs and chanteys in a soft and remarkably pleasing voice. The gray skies and listless ocean added a measure of authenticity and made me wonder how ancient mariners must have felt after weeks at sea under unfavorable conditions.

As the afternoon wore on and we continued northward the sky became heavier and the air cooler. Dampness was setting in and creeping into our minds as well as our bodies when I overheard the watchman mention the bridge. I looked forward and was greeted with a vision that overcame all else. The fog-shrouded headlands were joined by what looked like a long gray cloud and one rust-colored bridge footing. But as we came closer to our destination I had an epiphany of what the Golden Gate truly represents. Beneath the fog-laden bridge was a warm glow that increased in size and intensity the nearer we came. Before long, Angel Island appeared, bathed in golden light like a message sent from the heavens to let sailors know they have found a safe harbor.

It didn’t matter that the day had been cold and gray. It didn’t matter that we’d had no wind. What mattered was that we had shared a journey and arrived safely at our harbor — any day we live to sail another is a good day.

‘Maiden’: A Real-Life Drama and Triumphant Sports Documentary

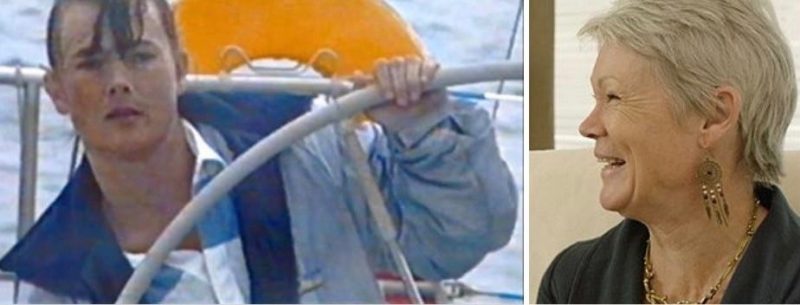

As the curtains drew back and the theater went dark, Maiden opened with footage of meaty Southern Ocean waves, old boats with archaic Kevlar sails, dramatic, crescendoing music, and the movie’s protagonist, Tracy Edwards, whom we caught silent glimpses of in the many countenances that defined her groundbreaking roles throughout the movie: determined, joyous, fierce, deeply stressed, and, occasionally, in tears.

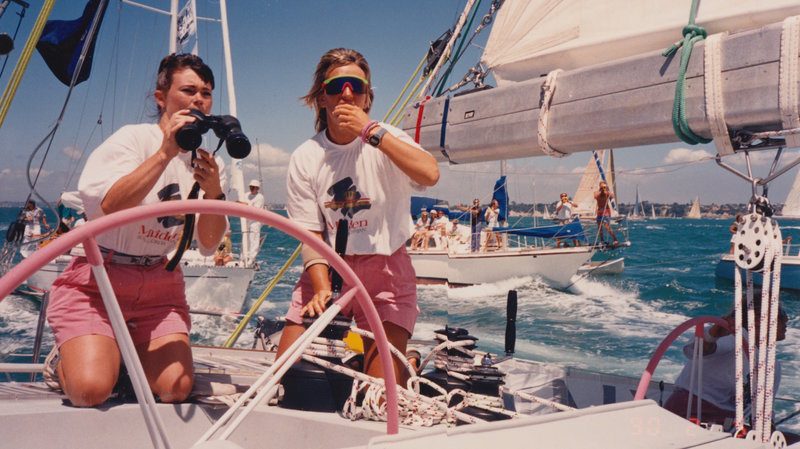

And yes, we teared up more than once during Maiden, which sank its hooks into us instantly and never let go. To be fair, we liked Maiden from the moment we first heard about it — a movie about a pioneering, underdog crew set in the big-hair and beamy-boated Whitbread Round the World Race in the late ’80s? Yes, please. Our objectivity was suspect from the get-go.

A documentary would never be considered a “period piece,” but Maiden’s characters and drama were set in a wonderfully bygone era of sailing and culture. Documentaries are also technically free from the three-act formula that dramatic fiction adheres to, but Maiden still went through several character-defining arcs as if it were a drama. Edwards’ father died suddenly when she was a girl, and the years that carried her to Greece as a young woman — where she eventually became a stewardess on boats — seemed empty and listless. Edwards talked about being homesick and lonely in Greece.

But once she started working on boats, Edwards found family, and said some of the men she worked with were like father figures. She did passages and began to hone her seamanship. “They had to tie me to the wheel while I was steering, because it was so windy they were afraid I was going to fly away,” she said in the film. After learning about the Whitbread, Edwards was determined to be a part of the race. She walked the docks, trying to hire on as a cook, but the teams were skeptical of having a woman onboard. She was rejected, but she persisted — thus setting, it seemed, a pace for the rest of the movie. Edwards crewed on Atlantic Privateer in the1985-86 Whitbread.

Like so many good documentaries, Maiden has current interviews with former sailors and journalists; the interviews serve as narration during grainy archival footage. (Our newest editor, who is in his mid-40s, relished the big, sloppy, bright-neon ’80s-ness of it all, and in the tragically dated boats. It was like watching a movie set in the ’30s and marveling at the old cars.) In one voice-over, Edwards said simply and flat-out, I just want to sail myself. We need an all-women’s team. In an interview on Fresh Air, Edwards said: “My mom always told me, ‘If you don’t like the way the world looks, change it,'” she says. “So I thought, OK, I will.”

Edwards was rejected, but she persisted. She finally got her friend, King Hussein of Jordan — whom she’d met while working a charter — to finance the team. Maiden crossed the starting line in Southhampton, England, in September 1989. They were bound for Uruguay on the first of six legs. The sexism the all-female team faced was widespread amongst both other teams and the media. They were asked patronizing questions about their makeup and relationships.

In the same interview with Fresh Air, Edwards said, “We weren’t surprised that there was resistance to an all-female crew in the race. We’re a maritime nation. It’s entrenched in our history, in our culture, and it is extremely male-dominated. But I was shocked at the level of anger there was, because why is this making you angry?” At the time of the race, Edwards said she wasn’t pursuing any feminist cause. “We’re only going out there and doing what we want to do,” she said. “In the ’80s, ‘feminist’ was an accusation. It had all sorts of horrible connotations, and really, it had been made into a word that women should be ashamed of — I think with deliberate reason. I was very young — I was 23 and 24. I didn’t want people not to like me.”

Maiden had a mediocre first leg, but won her class on the 7,260 Southern Ocean leg from Uruguay to Australia. Then Maiden won leg three from Australia to New Zealand in a tight, tactical battle, a type of racing that Edwards admitted was not her strong suit.

And for Edwards, the larger picture of what she and her team were doing came into focus. “When we got to New Zealand and we won that leg and we were getting the same stupid, crass, banal questions that we had on every other leg, I just thought, this is bigger than us, bigger than Maiden, and bigger than anything we’ve been tackling. This is about equality. And I think I am a huge, fat feminist. I stood up for the first time in my life and I said something that might hurt me and might make me not likable, and I took pride in it, and it was an extraordinary experience.”

Maiden had a difficult leg four, and the film began to do a meta-close-up on Edwards — especially now that her team was the boat to beat. The race itself seemed to fall out of focus and gravitate toward the confounding stress on Edwards. We’re almost tempted to critique the film here. Maiden’s standing in the race became unclear. There were subtitles that said how many total days the crew had been at sea which were a little confusing.

As Maiden sailed back into Southhampton and into the film’s conclusion, we also found it a little unclear, at first, what point was being made, though it was obvious that it was less and less about the race — even though the race was everything to Edwards and the crew. In fact, Maiden would take second in her class overall, “Which is the best result for a British boat since 1977, and actually hasn’t been beaten yet,” Edwards told Fresh Air. “But that didn’t mean much to us at the time. When you finish a race like that, you go through a mixture of emotions. We hadn’t won; we’ve come second, and it took me a long time to come to terms with that, because second is nowhere in racing. [But] there was a bigger picture, and the bigger picture was what we had achieved.”

Ultimately, we think the film did well to shed the veneer of the Whitbread and to allow the crescendoing emotions to speak. Maiden received an epic reception sailing into Southampton, and one of the final scenes of the movie is of Sir Peter Blake presenting Edwards with the trophy for Yachtsman of the Year. Needless to say, she was the first woman to be bestowed with that honor.

Edwards said it was extremely difficult to say goodbye to the crew and figure out what was next.

“When you finish a race of that length, you realize this family of people that you have been with for three years is suddenly going to disappear,” Edwards told Fresh Air. “It’s quite shocking and can be depressing. I didn’t have any plans and it didn’t go well. I fell off a cliff really. Within nine months of the race finishing, I had a nervous breakdown.”

Maiden, the boat, is coming to San Francisco. And so is Tracy Edwards

For roughly 10 days at the end of August, Maiden — the original 58-ft 1979 Bruce Farr-design Disque D’Or III — will be in the Bay Area as part of the Maiden Factor world tour, a fundraising event for the global education of young women. On Saturday, August 24, Tracy Edwards and crew will be onboard Maiden at Pier 40 in South Beach Harbor from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m., followed by a reception at South Beach Yacht Club at 6 p.m.

We will have more information on ‘Lectronic Latitude and our Facebook page as the event draws near.

Maiden, the movie, is currently in a theater near you.