Reader Submission: Sunsets

Reader Lee Panza snapped two amazing photos off Oyster Point on New Year’s Day.

"The first sunset of 2018," he wrote us. We are clearly off to a good start. Happy New Year everyone, and thanks for reading ‘Lectronic Latitude. And remember, if you have a good photo or story you want us to share, please send them here.

Express 27 Fleet Races to Hawaii

Division starts for the 2018 Pacific Cup will commence on July 9 in front of the St. Francis Yacht Club. For the first time in the event’s 20-year running, there will be an Express 27 one-design class with eight entrants. Alternate Reality, Bombora, Fired Up!, Loose Cannon, Magic, Motorcycle Irene, The Pork Chop Express and Yeti will oppose one another for 2,070 miles.

©2018Latitude 38 Media, LLC

Christopher Jordan and his wife Charlotte will pair up on The Pork Chop Express. Christopher has made several ocean crossings, plus competed in a Pac Cup on the Santa Cruz 50 Hula Girl, but this will be a first for Charlotte. “We’re racing as San Francisco E27 class race neophytes,” he says, noting they have had the boat for only one year. Christopher grew up on dinghies and keelboats, eventually spinning things into a vocation. Less of a hard core racer, “Charlotte takes a more relaxed approach to sailing, which usually makes it more fun.” As to the boat’s moniker, “There’s an opening scene in San Francisco’s Chinatown for Big Trouble in Little China where Kurt Russell is driving a big rig named the Port Chop Express. We discovered the name was initially used by commissioned WWII vessels that transported provisions and supplies to the South Pacific Theater; Pork Chop Express boats took a while to arrive but averaged 10 knots.” Christopher indicates that the film also has many usable quotes suitable for situations aboard a boat.

Rebecca Hinden of Bombora has staffed up with full crew. “I have chosen to go with three, which means a bit more weight, water and food.” A fourth-time racer across the Pacific, she’s undaunted by the scale of things, noting that the Express 27 is a great ride — upwind is easy, it planes well, it’s fun to drive, and loads on the lines are less. “It’s a little boat on a big ocean.” She and peers enthuse over the merits of one-design racing on a long ocean course, plus the fact that each crew will know its ranking as things unfold.

Over on Motorcycle Irene, Will Paxton will saddle up with Zachery Anderson. “Doublehanding is something I have not yet done and is a new challenge,” states Paxton, a veteran of seven Pac Cups, eight Transpacs and four Pacific Ocean deliveries. “You are basically singlehanding, but with rest stops.” He’s looking forward to seeing the ocean and surfing the waves, plus braving dark nights as lone man up top like never before. “Wind and weather could be anything, so I adopt a Zen attitude about seeing it through. All kinds of crazy things are out there — whales at the Farallones, huge floating objects, commercial and Naval traffic, whale sharks, shooting stars and incredible sunsets and night skies.”

Manning Alternate Reality will be Darrel Jensen, raised on racing in the San Francisco Bay Area. By age 15, he had participated in his first Pacific Cup aboard his father’s Cal 39. Jensen tackled the 1982 and 1986 events on a Farr 48, did the 1987 Transpac, then the 1996 Vic-Maui. In 2006 he purchased Alternate Reality; he and a brother sailed her in the 2008 and 2016 Pac Cups. “This year my son will accompany me on his first Pac Cup. Doublehanded on a small boat means life consists of sailing and sleeping. People have often asked if my brother and I were still on speaking terms when we got there. I laugh and say that other than a short strategy session in the morning and one in the evening, we hardly saw each other.” Conditions require racers to “Drive until you can’t remember how you got on the last wave — and just to the point where you’re about ready to drop off into sleep. Then you pound on the deck to wake the other guy.” Shifts on his boat will run three hours — or until the driver just can’t do it anymore.

Taking things in stride on Magic will be Mike Reed and Jeff Phillips. Reed has sailed this event three times on a crewed boat; 2018 will mark his second time doublehanded. “In 2012 we placed second in our division, so expectations are high.” A trauma flight nurse by profession, Reed has participated in numerous big events around the globe and writes about his adventures. Sailing since a young lad, Reed reckons he’s logged 25,000 racing miles. “We’re hoping for good wind in the 20- to 25-knot range and following seas.”

To start, crews will see a challenging reach down the California coastline. Says Jensen, “The first couple of days are generally pretty breezy, followed by a few days of very pleasant sailing. The 2 a.m. squalls add excitement and adrenaline to the mix, but back in 2008 it took us until 2 a.m. to just pass the Farallones!” The finish is off the north coast of Oahu, near Kaneohe Bay. The Schumacher-designed Express 27s automatically qualify to be considered for the Carl Schumacher Trophy — first to finish on corrected time takes the prize.

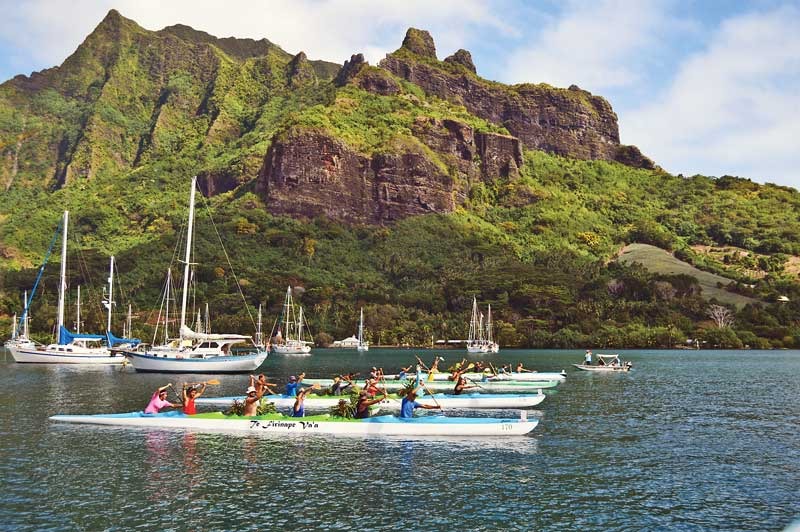

The Pacific Puddle Jump Starts

When would you set sail for the South Pacific Islands? If you’re one of the more than 80 boats already signed up for the 2018 Pacific Puddle Jump the answer would be this January to April, meaning there’s a slim chance there will be any close maneuvering on the ‘starting line’ which stretches almost 4,000 miles from Southern California to Panama. It may be the world’s longest starting line with the most relaxed starting sequence, but that’s in keeping with the concept of a cruising rally.

©2018Latitude 38 Media, LLC

While most boats hail from the West Coast of North America there are boats from Japan, UK, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, New Zealand and more. Boats range in size from the Shannon 28 Summer hailing from Sausalito to the 60-ft Lodestar 55 Tribasa Cross with a hailing port of Albuquerque, NM, and average about 45 feet in length. If the past is any predictor of the future, by the time everyone has set sail to head west, the fleet will consist of around 200 boats.

We suspect most of these people didn’t spend the last week of December wondering, "Should I prepay my 2018 property tax bill?" and are already well south enjoying the cruising life in Mexico or the Caribbean. If you’re among that group, we’d suggest signing up to join the rest of the Pacific Puddle Jumpers on the sail west. You can learn more at www.pacificpuddlejump.com.

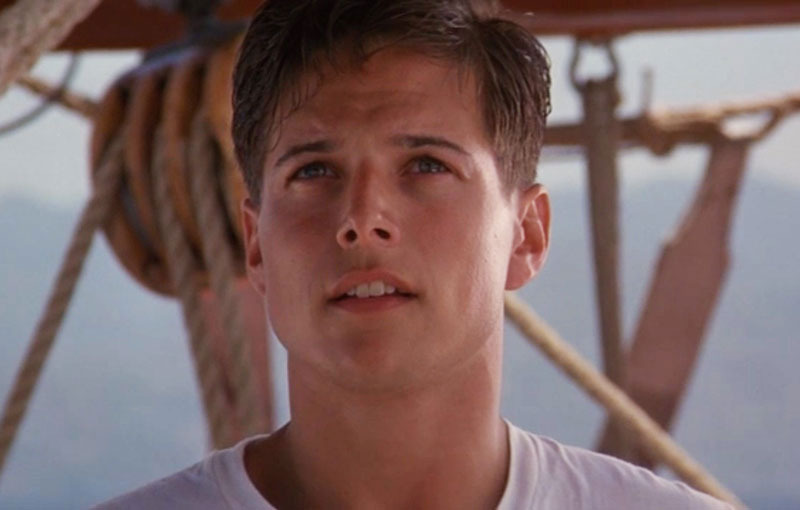

The Latitude Movie Club: ‘White Squall’

Working at the Navy Sailing Center, Point Loma, in my early 20s was a formative experience — I was a few years older than the real-life boys portrayed in White Squall, but I was constantly learning lessons in adulthood, responsibility, and diplomacy.

On a windy fall weekend, I was keeping an eye on our renters when I spotted one of our O’Day 14s having a tough go of it. The boat was a little swamped and the woman at the helm was shivering, but she told me she was fine and game to sail back. I don’t remember what I said, but I knew I had to convince to let me tow her without being patronizing. I convinced her, and she was more than game to get warm and dry. Chatting on the way back, she told me that she was from the East Coast and learned to sail as a young girl.

“Do you know who Chuck Gieg is?” she asked. The name was strangely familiar, and in moments, neurons connected. Chuck Gieg was the narrator of the movie White Squall, and the real-life survivor of a shipwreck in 1961. Gieg’s book, The Last Voyage of the Albatross, would be adapted into the screenplay for the 1996 film. “Chuck Gieg taught me how to sail,” the woman said proudly, adding that the movie was, according to Gieg, fairly accurate, with a few typical Hollywood dramatizations. (Nobody harpooned a dolphin, for example.)

As sailors, we don’t get sailing movies very often, so the release of White Squall was a boon for sailing nerds — which was proudly me at the time. And because it’s set entirely on and around a brigantine, White Squall might be one of the most sailing-est of all sailing movies of all time.

Watching the movie last night — more than 20 years after its release, and after my tastes in movies have shifted dramatically — some aspects of the film stand the test of time, while others lack the gravitas they had when I was in our early 20s.

The movie is full of shirtless teenage heart throbs before they were widely famous — but they were still totally dreamy. There was Scott Wolf (playing Gieg), Ryan Phillippe and Eric Michael Cole. In act one, Gieg narrates: “Some of us are here for discipline, some of us are here for escape, and the rest don’t even know why. I’m not sure where I fit in but I can see a small piece of myself in each [of the others]. I think I’ll have friends here, and I hope this will be home.”

In this sense, the movie covers multiple genres. In addition to be a ‘sailing film’, it’s also a teenfest, a coming-of-age film showing the arc of boys becoming men. I felt the same sentiment re-watching the film that reverberated through me after seeing it for the first time: I wish I’d done a semester at sea. I would have grown up as an entirely different human being.

The movie also has some excellent sailing, with the big, bulky brigantine chugging along in heavy seas and cruising to exotic locales. It is a truly excellent sailing movie, plowing constantly, inevitably toward disaster in that anxious Hitchcock way — we the audience know the characters are doomed, while the characters themselves are oblivious.

But at the same time, parts of White Squall came across as incredibly contrived, as if the film were desperate to be dramatic and taken seriously. Captain Christopher Sheldon was played by Jeff Bridges in perhaps his most strait-laced role of all time. For those of us who know him as The Dude from The Big Lebowski, Bridges was very ‘UnDude’ in White Squall (even as the President of the United States in The Contender, Bridges still felt like a laid back hippie ready to ‘do a J’).

Bridges played a perfect hard-ass, no-nonsense, always-scowling skipper, but some of his lines (and the timing of their delivery) felt contrived. He launched into countless wise-old-skipper diatribes about the need for order and discipline, and the dangers awaiting the boys out at sea. (At one point Bridges says, to himself, “Behold the power of the wind.”)

Eric Michael Cole’s character of Dean Preston felt especially over the top. “Let me tell you girls something, I do what I want to do when I want to do it, and I don’t give a damn what some Ahab up there says otherwise.” We get it dude, you’re a super badass. But Preston would go on to be vulnerable, breaking down when he wasn’t making the grade and asking his shipmates for help. As dramatic as it might have tried to be, you still felt part of the crew of the Albatross, and thus felt part of the tragedy when the ship met its fate in a brief, violent storm.

The movie ends with an “Oh Captain My Captain” moment not at all dissimilar to Dead Poet Society, when the boys come together to rally behind their skipper, who is under assault in court. Their mantra: “Where We Go One, We Go All.”

This courtroom scene apparently never happened (though this wasn’t something the woman I gave a ride to in San Diego told me). According to a 1996 New York Times article, “none of the survivors, both by happenstance and design, ever talked again, until recently, when the movie White Squall was being released.”

Tod Johnstone, one of the students aboard the Albatross, and Sheldon said the release of White Squall was therapeutic. “It has given them an opportunity to purge feelings dormant for too many years.” Sheldon died in 2002 at the age of 76.

We don’t disparage art for imitating life, and for taking certain licenses to make that art competitive in the marketplace. But what’s always interesting is the way that art changes as one ages. What was awesome in your 20s can be cringeworthy in your 40s. But the sailing itself tends to stand the test of time.

Have you seen White Squall recently? What did you think?