Will a Split Ring Bring the Mast Down?

A classic, evil tactic to unnerve any racing competitor is to leave some loose cotter pins, clevis pins, split rings or other fasteners on the deck to undermine their confidence that their rig will stand up. It’s harder to push your boat in a windy race if you started the day finding a mystery clevis pin lying on the deck before, or during, a race.

Having recently purchased our 1989 Sabre 38 MkII, we’ve reviewed and upgraded the items flagged by our surveyor. One thing we did not do before purchase was a rig inspection. So we thought we should head up the mast to see what’s up there.

To our untrained eyes all essentially looked fine for a rig that’s been standing out in the elements for 32 years and had its standing and running rigging all replaced in 2016. We also had a rigger run up the mast, and all that was found was a scratch on the leading edge, some pitting, and signs of rust that probably came from old wire halyards.

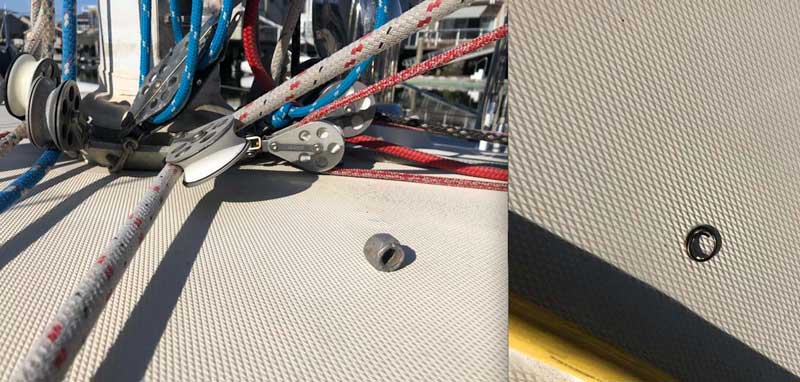

The unnerving thing was back on deck when, within a week, we found both a nut and later a split ring just lying on the deck. We glanced around, searching for the devious Friday night beer can racer who might have been trying to undermine our faith in our rig, but found none. Upon further searching we found the nut lay right about at its source, which was the lower end of the bolt holding the vang to the bracket on the mast. It’s now replaced with some Loctite gel, which we hope will prevent a repeat.

The split ring was harder, until we remembered that just ten minutes before the start of the Friday night race the mainsheet had become detached from the traveler, requiring quick, emergency repairs. The air was light and all went smoothly, allowing us to put it back together before the starting gun (now horn) fired.

There’s a lot going on at the base and top of the mast, which makes it worthwhile to have a periodic look. As this past weekend demonstrated, the Bay is a windy place, and we felt better during our two reefed-down, 30-knot apparent wind sails knowing that we’d been up the rig and found all the pins in place and everything looking solid.

It reminds us that one of the fundamental aspects of sailing is just paying attention. When you’re out on the water you’re looking for wind shifts, tidelines, weather conditions, ship traffic and other factors that may impact or improve your sailing. The same is true when you’re at the dock. It could be an oil change, turning the thru-hulls, tightening hose clamps, or periodically finding a friend willing to crank you up the rig. (Thanks, Randy!) It’s all part of the fascination of getting to know your boat and how you and it engage with the world.

What unnerving things have you found on deck? Or what should we be checking more frequently? Should we have had a rig survey? The only question remaining for us is, did the nut and split ring fall off on their own, or do we have a truly malicious competitor with a crescent wrench and needle nose pliers?

When I first sailed My Santa Cruz 27 Yellow Jack I discovered an aluminum clevis pin in the starboard upper shroud lower turnbuckle. It appeared to have been in place for some time but when I bore away from Southampton it failed , broke in 3 pieces. An instant crash tack saved the mast. No idea there were alloy pins or who put it in or why.

Aluminum is susceptible to corrosion assisted fatigue cracking and aluminum does not have a fatigue endurance strength. These two characteristics mean that the risk of fatigue fracture increase with age and corrosion severity. My experience is that its the corrosion you can’t see, such as is occurring in a fastener thru hole, or other loaded areas, initiates failures. I would be concerned whether the reported “scratches” on the mast leading surface have initiated fatigue cracks and if so what is the rate of crack growth. Marking the defect ends with a metal marking pen and checking whether the indications have grown past the end marks would be useful. Corrosion is also likely occurring at the spreader bar joints, tip cups, and at the bottom of the mast step assembly.

After 32 years of seawater exposure, a good winter project would be to pull the mast out of the boat (send it to Buzz Ballenger for refit). The refit scope should include mast disassembly of all components (easier said than done), glass bead blast and conduct a thorough visual and liquid penetrant examination. Carefully inspect any welded attachment to the mast, gooseneck, and mast head. The rigging company should be experienced in aluminum welding to repair corrosion damage, reinforcing worn wall thickness with saddle patches. Sand or grind out the “scratches” to sound metal and fill with weld, grind weld cap to blend with extrusion surface. The mast should be chemically cleaned, etched, primed and painted with Awlgrip coatings. Awlgrip painting system is much more reliable than anodizing to prevent corrosion.

Refit all the parts and bed mixed metals with Tefgel or use G11 shims to separate different materials. Every fastener should be bedded in Tefgel. The standing rigging should be very carefully inspected, if the wire is magnetic or is rusting, replace it with Nitronic 60 wire rod.

Replace all the wiring and coax with high quality tinned strand copper. Lights should be replaced with LED units. Install all interior wiring in mesh sleeve “conduit”. Add a lightening rod and earthing conductor. If the mast step is an aluminum casting, replace with a mast step fabricated from G11 plate. Baffle the mast interior for a water seal and make a drain above the mast entrance to the cabin trunk. Be sure to check the internal structure that the mast is stepped to, if the structure is “soft” or “spongy” now is the time to replace it with a carbon fiber pedestal.

All shackle pins should be safety wired.

I hope this information is useful.

Enjoy the summer!

Marcus – good to hear from you and thanks for the thorough and thoughtful reply. Sounds like I’d have to miss more than one weekend of sailing but will take this into consideration. First up may be to get my friend Randy to grind me up again with a marking pen. I did notice that the bulbs are already LED so that’s a good step. We’ll enjoy the summer and keep an eye out for split rings and opportunities to prevent any future problems.

Very helpful guidance — thanks for sharing!

Not quite mast-threatening, but. In the 1980s the Newport 30 Association had problems with “boat lightening.” Tables, doors, stoves, drawers, cushions, “factory installed” stuff disappearing from boats. The fleet measurer, who seemed to have a key of every marina, would come by and take a look at boats. If you arrived one Saturday morning for a race and found a string with a washer hanging from your stem fitting you knew he’d been there. If the washer was dangling in the wind you knew you’d get a note in the mail (no email then).

Last summer we had a great day sailing around Angel Island. In the lightening evening wind sailing downwind back to Emeryville, we were all enjoying the sunset when for no reason at all I thought “I’m gonna have a look around the boat.” I started at the gooseneck and found the cotter pin and washer were gone and the pin was holding the boom on by a thread! We doused the sails, motored to the dock and were able to repair them before heading home. Another example of when your gut speaks to you, listen.

Chainplates! Remove them if you can, if you cannot, take off the fitting and try to bend the plate sideways with a vice grip. Electrolysis attacks them at deck level where you can’t see and they become very weak. A common cause of dismasting on an older boat.

We had a good surveyor go up the mast when we bought our boat, an 1988 Cal 39. He noted that the upper shroud ends were immobile in their caps due to lack of lubrication and he recommended unstepping the mast and going through it. We had a good rigger do just that. He found quite a few problems with the rigging. It was replaced…

John,

A few specific thoughts in response to your open questions:

1. Yes, over the years I have found nuts, cotter pins, and other assorted boat bits on deck. Sometimes they really have worked loose and need to be urgently replaced; other times I concluded they were items I had misplaced during a project and never fully cleaned up — also a lesson!

2. Yes, nuts or equivalent fasteners not affixed with Locktite or equivalent (or not being NyLock or other self-locking nuts), have a remarkable ability to gradually detach themselves over time given a combination of the inevitable working of the rigging, and vibration of all sorts, whether from a taut sheet or running under power or whatever. The lesson to me is that any critical nut (or similar fasstener) should either be replaced with NyLock (or equivalent), re-installed using Locktite, or otherwise replaced with something that is designed to resist loosening under all circumstances. (As a side note, I suspect I may have “The Worlds’ Largest Private Collection of Stainless Steel Nylock Nuts.”)

3. Another item to inspect are all halyards, especially where they pass over a sheave at the mast head (or through a block, in the case in spinnaker halyards) when tensioned. When circumnavigating the Pacific I would regularly inspect the rig before any long passages, and we found chafe severe enough to merit replacing the jib halyard once and the spinnaker halyard once (each after somewhere on the order of 10,000 – 15,000 miles of sailing). Having had some notion of this possibility, as well as an obsession for tools and spares, we were carrying a spare for each — which were put to good use!

4. Speaking of spares, I believe anyone planning an ocean passage (including coastal passages, especially on our unforgiving West coast) should carry tools and parts to effect emergency rig repairs — including lengths of appropriately sized 1×19 and 7×19 wire, wire clamps, thimbles, and, if possible, Hi-Mod, Norseman, or Sta-loc fittings, as well as the tools to use them — ideally including a wire cutter sufficient to cut the heaviest standing rigging on your vessel. Unlike our spare halyards I’ve never needed to use these — although we did have a headstay fail half-way between Truk and Guam!

Fairs winds, and may your stock of spares never be depleted