Remembering the Big Bang

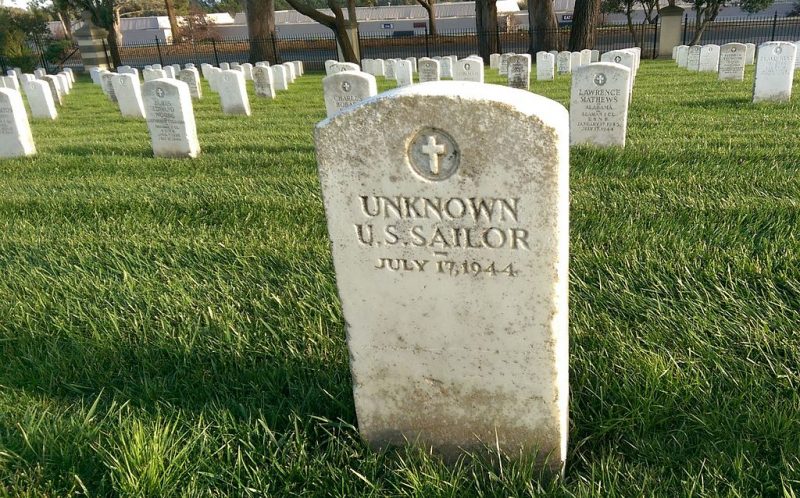

This month marks the 75th anniversary of one of the most horrendous events of World War II, which occurred right here in the Bay Area. On July 17, 1944, a mishap at the Port Chicago Naval Magazine (site of present day Concord Naval Weapons Station on Suisun Bay) triggered a massive explosion that killed 320 sailors and civilians; injured another 390; destroyed two ships, an entire pier, a railway and a locomotive that was on it; shattered windows as far away as San Francisco: registered 3.5 on the Richter scale at UC Berkeley; and blew shrapnel so high into the air that a pilot flying over the area saw debris flying by at 9,000 feet. It was the worst loss of life during the war not caused by enemy action.

The incident also signaled a landmark case in race relations — 202 of the dead and 233 of the injured were African-Americans, who accounted for 15% of all African-American naval casualties during World War II. When asked to go back to work a month later, 50 survivors of that day refused. The “Port Chicago 50” were eventually court-martialed, dishonorably discharged, and thrown into prison for 15 years for mutiny. A young lawyer named Thurgood Marshall finally brought the government to its senses — the men were all released 16 months later. The landmark case led the Navy to become the first branch of the military to desegregate its ranks beginning in February, 1946. Oh, and they adopted new standards for the safe handling of munitions, too.

In 1999, President Bill Clinton granted a presidential pardon to Freddie Meeks, one of the last surviving members of the Port Chicago 50.

Just last month, concurrent resolutions passed by Congress recognized the victims of the explosion and officially exonerated the Port Chicago 50 “in order to further aid in healing the racial divide that continues to exist in the United States.”

A detailed and award winning history of the event and trial was written decades ago by Robert L. Allen, now on the faculty at U.C. Berkeley.

• The Port Chicago Mutiny : the story of the largest mass mutiny trial in U.S. naval history / Robert L. Allen.

I was less than one month old, sitting on my mother’s lap in the living room of our rented home on Alabama Street in Vallejo, CA, when the explosion occurred about 20 miles away and blew the picture window in on top of us. Of course I have no memory of the incident, but mom later told me we were lucky to have survived.

Scientists and engineers working on the atomic bomb visited the scene to study “the effects of the detonation.” The team was led by Capt. William S. Parsons, who headed the Manhattan Project Ordnance Division and was the man responsible for creation and delivery of the atomic bombs. Though best known for his role in arming the Little Boy bomb as the Enola Gay B-29 Bomber flew to Hiroshima, Parsons went on to serve as Technical Director for Operation Crossroads, the spectacular and public 1946 tests of atomic bombs against naval ships, and later became the first “atomic admiral”, instrumental in establishment of the Nevada Proving Ground and in setting U.S. nuclear policy. In a 1948 speech to the Naval War College, Rear Admiral Parsons acknowledged that the data from the Port Chicago explosion provided the first realistic expectations of the damages from an atomic bomb.