Navigating a Gale, and Darkness, in California

As we reported on Monday, the Golden State is at the bitter, ugly end of its now-endemic fire season, and grappling with the realities of its “new normal.” As of yesterday, California was still under states of emergency as rumors of another “wind event,” which can instantly spark terrible fires, echoed through the news and a nervous Bay Area population. While there is a little breeze today, the skies in the East Bay — where we’ve sought refuge from the power blackouts — are mostly clear of smoke. The worst seems to be over, for now, though life is nowhere near back to normal, whatever normal may be.

Ever since a gale blasted through Northern California early Sunday morning, life has been a little scary in pockets of the Bay — and also just plain inconvenient. Much of Marin County, which is home to the Latitude offices and most of the staff, was without power since the early hours of Sunday morning (though it now looks as if power has largely been restored). What might seem like trivial matters — no refrigeration, internet or ability to charge devices — can become grindingly vexing.

There are the statistics of these disasters: The number of acres burned, the number of people evacuated or without power, and the losses to businesses affected by both the catastrophic and the inconvenient. But then there’s the effect it has on your mind and your life, a measurable toll in people’s anxiety, fear and frustration.

The word apocalyptic is common when Californians talk about their situations. The atmosphere is dark — figuratively and literally. (Admittedly, effects from fires and power outages are so compartmentalized that in a town just a few miles away, life might seem completely ‘normal’.) We’re sure that it’s the same for people living through hurricane, typhoon and tornado seasons; you probably just hope that this year, it won’t be too bad, that it comes and goes quickly, and that you and your property escape it unscathed.

The current state that California finds itself in — which now spans its last three wildfire-ridden autumns — is a bit beyond the scope of this magazine, other than perhaps a few analogies, and reporting on the extreme nature of Sunday’s gale. The Bay Area is no stranger to big breeze, but Sunday’s wind was extraordinary, and had a wickedness and ‘grip’ rarely seen. There were “hurricane-strength” gusts of more than 90 miles an hour.

“Northern California was battered Sunday by extreme Diablo winds,” The Los Angeles Times reported. “The National Weather Service clocked a gust of 96 mph in the Mayacamas Mountains northeast of Healdsburg, which is threatened by the 54,000-acre Kincade fire,” which started a few days before the gale hit. On what is currently California’s biggest blaze, firefighters did extraordinary work to keep the Kincade fire under some semblance of control as the winds raged and mercilessly fanned the flames.

I was driving back from a blacked-out Napa to Marin on Sunday, and there was just enough internet trickling into a friend’s phone to announce that there was a fire in Vallejo. “Twin fires — one in Vallejo and the other just across the Carquinez Strait in Crockett — erupted Sunday morning, causing evacuations in the two counties and shutting down Interstate 80 and the Carquinez Bridge,” the San Francisco Chronicle reported.

Cal Maritime Academy was evacuated as the fire, which is still considered active but largely contained, crept onto the easternmost corner of the campus. “All cadets, staff and faculty were evacuated safely,” Pete Steyn, a Cal Maritime IT employee, told us.

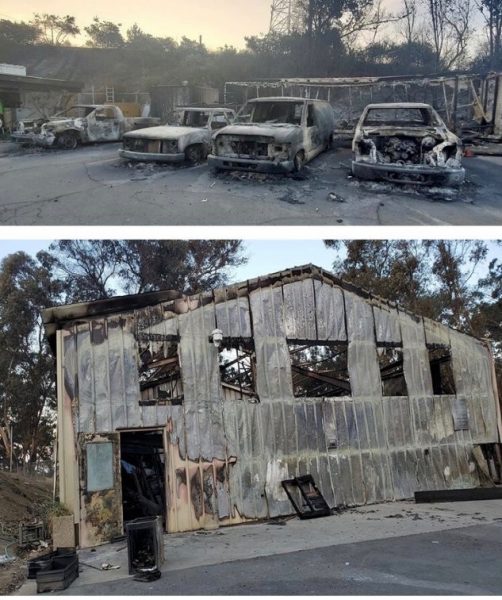

Steyn’s fiancée is the second engineer on the training ship Golden Bear, which is doing watches “with a skeleton crew at the moment to try to keep the amount of people on campus minimal,” Steyn added. “We are hoping to reopen campus on November 4 after all buildings have been declared safe. The only building we lost was the auto shop and a few cadet vehicles, a few sailboats and few campus vehicles.”

Chris Carranza, who’s a student worker in the IT department an engineering cadet at Cal Maritime, said on his Facebook page that when he evacuated from Glen Cove, “we were under the impression that our house was going to burn down.”

It is difficult to quantify the pervasive worry from these last few Octobers, when the moist Pacific sea breeze has fizzled out and California is parched and dusty. We can’t imagine the tragedy that some people have lived through, nor the fear and uncertainly of being forced to evacuate.

With I-80 shut down on Sunday, I found myself anxious to drive on Highway 37, which is a narrow and at times one-lane road that skirts the rim of San Pablo Bay and passes through the bone-dry fields of western Napa County. “What could possibly go wrong?” I joked to myself. There was no internet and no way to check the traffic, and I worried that my car, which is getting old, would break down. Like a sailboat with no wind and far away from port, I had to rely on my engine.

Everything in Marin was closed due to the blackouts. There were no groceries or gas, and refrigerators went warm after a while. You roll with it at first, and when annoyed and bored, you remind yourself how lucky you are compared to people not far away. But at some point, life has to go on, and you have to get back to work.

Everyone asks if this is California’s “new normal.” Some context: There have actually been fewer fires this year, so far, than in the previous two. As of October 4, 2019, there were “41,074 wildfires compared with 47,853 wildfires in the same period in 2018,” according to the Insurance Information Institute, or III. (There were 71,499 wildfires in 2017.) The III said California is by far the number-one state vulnerable to extreme wildfires, with 2,019,800 properties at risk. Texas, the number-two state at risk, has 717,800 vulnerable properties.

On Sunday, I forgot to grab my one and only flashlight while at the boat, so I rode my bike back into town. The occasional leaf hit me in the face with a sharp sting. My bike and I were pure windage. Throughout town, I heard the occasional high-rpm, lawn-mower-like rattle of generators and the smell of gas.

Riding through an empty San Rafael, which is otherwise always busy on the weekend, was eerie and unnerving — quite simply, apocalyptic. The only place open was Terrapin Crossroads, which had a big generator running to power the band, a TV showing the World Series, and the machine that charges your card. All beers were in cans.

Not to fear, Latitude Nation, there are oases in the apocalypse, and they serve $8 12-ounce cans of IPA. Be sure to bring your debit card to the end of times.

Epilogue

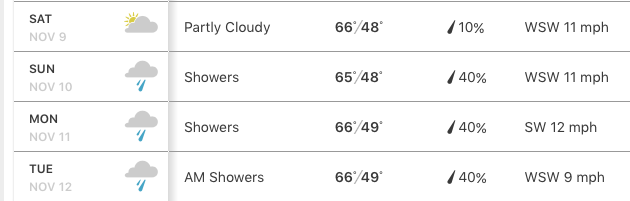

There is, blessedly, rain in the Bay Area’s forecast. We are holding our breath.

This story has been updated.

Exactly in line when California stopped forest management which Governor Pat Brown wisely started. After the Reagan years, this went out the window.

How can you opine on “a new normal” without mentioning PG&E? I have lived in Marin for almost all of my 66 years. Graduated from SRHS in ’71. It has always been windy in October. And the hot, fall offshore winds were in contrast with the summer, onshore prevailing NW breezes. And surprise, the vegetation is always dry around this time of year.

So, what changed? IMO, it is the pigeons coming home to roost on the neglected maintenance and capital improvements both required by CPUC of PG&E. The common decency required of our electricity provider to do everything it can to protect us was clearly demonstrated as not a priority for them after they were found guilty of multiple felonies in the San Bruno tragedy. Their complete disregard for the long known and incontrovertible truth of climate change in terms of planning and preparing just adds another element to their culpability. This isn’t a new normal. It is a criminal conspiracy that operates with a big moral hazard- the fact that the state (CPUC) gave them a pass due to heavy conflicts of interest by many past commissioners, and lax oversight by the governor and legislature of that body.

There’s much to do to fix this but we must stop calling it a “new normal” last we legitimize it. It was and is a crime to operate this electric utility in this negligent manner!

Dane — Thanks for this. We agree with you 100%. You’re right, this isn’t normal. Normalcy is a lie we tell ourselves when things are going terribly wrong and we’re just trying to get through it. We’re looking forward to publishing this in the December issue’s Letters.

In the Palmer-Wasilla area of Alaska we suffered multiple outages during winter as branches took down lines during ‘weather events’; we were prepared for them. The local electrical co-op had hundreds of miles of lines to patrol on dirt roads through forest, but keeping the lines clear was a priority. It looks like PG&E did not have the same priorities, but one must also look to the oversight bodies who were lax, if not chummy. Big business requires vigilance and reality checks it comes to billion-dollar tragedies.

Excellent summary of the fires in Northern California. California is losing her crown in many ways. Since 1995, I have watched the desert plants creep North. Back then Northern California had a Cascadian, mossy, moisture. Today that wet has evaporated away, along with some of the other good things about our State. What happens when a Garden of Eden turns dry. It fails to bloom and eventually burns.

Bad news, PG&E and their regulator is “US” the rate payer/tax payer.

There is no Big Business here because all loses are eventually put on US.

Pension fund loses, rate increases, insurance premiums, increased taxes and

who among those in charge lost their jobs or suffered financial harm? No one.

The big high power lines should follow rail lines for access, maintenance

and emergencies. Longer and less efficient but much better. Remote communities

and remote residents need to assume their own higher risk of loss without everyone in the

State picking up the bill for their county lifestyle.