Zingaro’s Bad Break Is Bad Break

Two days before Christmas, James Evenson and Kim Jensen were on final approach to Honolulu from the South Seas aboard their Spindrift 37 cat Zingaro when things went terribly wrong.

They were in washing-machine conditions about 40 miles southwest of the Big Island. The winds were blowing 30, the seas were 20 feet, and the wave trains were coming from three different directions. In three years and 25,000 miles of sailing together, they had never seen anything like it.

Zingaro was on starboard tack, with only a ‘postage stamp’ of jib out, dragging drogues, and still making 6-7 knots over the bottom. At 2:30 a.m., the boat was picked up by one wave and slammed down by another, followed by a wrenching motion and “a tearing sound like ripping cured fiberglass off a piece of plywood,” says James, a former Bay Area resident.

Ironically, that’s exactly what happened, but on a horrific scale: The starboard hull had broken off! “The rear main beam was broken, and subsequently all of the bulkheads and stringers on the starboard side,” says James. “A lot of the hull-deck joint also failed.” All that was holding the hull to the rest of the boat was part of the deck.

The couple immediately sprang into action, getting the jib down and stopping the boat. Kimmi got the idea of lashing the errant hull to the intact part, and James jumped below for a coil of 3/8 Dyneema he had saved from re-rigging Zingaro the year before.

The only way to do the deed was for someone to get into the water. James had gone under the boat at sea before, even at night, to get a net off the prop or untangle a fishing line, but none of those nights came close to this one. As he worked to secure the line around the starboard strut and prop shaft, the stern was continually flying up and crashing down, threatening to alternately suck him under or crash down onto his head. Or both.

He managed to get the job done and get back aboard, only to have the strut fail and the shaft bend 20 minutes later — not only necessitating another swim, but rendering the starboard engine useless.

Buy the time the Coast Guard cutter Oliver Berry arrived from Honolulu later that night, Zingaro was as secure as she was going to get. The conditions had abated a bit, and James had motored closer to the lee of the island using the port engine.

Right after it happened, James and Kimmi — who met in Mexico in 2017 — had considered abandoning the boat, but by the time the Coasties arrived, they had decided to try to nurse Zingaro the last few miles to landfall. With the cutter escorting, they putted along at three knots, finally making it to Honokohau Harbor on the Big Island on the morning of the 24th. “My hat is off to the Coast Guard, specifically the Honolulu OOD and crew of the cutter Oliver Berry,” says James. “If you are reading this, thank you, gentlemen — you saved us.”

At this writing, Zingaro is at a boatyard in Lahaina, Maui. The boat was not insured. James hopes to find a new owner with the drive and desire to fix her up just as he did when he acquired the boat in 2016 in Florida. Meanwhile, he and Kimmi are looking for a ‘Zingaro 2.0′, although they don’t know yet if it will be a mono or a cat. They are being helped already by donations from subscribers to their YouTube web series who are interested in helping with the next part of the Zingaro adventure.

Look for more on this incident in the March Changes In Latitudes. In the meantime, you can learn more at www.svzingaro.com.

Lessons from the Three Bridge Fiasco

One of the great lessons you learn from the Three Bridge Fiasco is humility. Every year you start with the sense of great possibilities. There are so many twists and turns in the course that you figure it’s a crapshoot and anyone could win. Even you! You spend some time the night before (the truly dedicated spend the week before) figuring out the currents, checking the wind forecast, and making a firm commitment on which way to go.

Then race day arrives. You go down to the docks and all your commitment unravels. You talk to your dock neighbors who have committed to an entirely different course. After discussion with other skippers you reach consensus by each deciding to go a different way. At the start line the wind is a little different than expected, and more boats start in an unexpected direction, further eroding your confidence. Eventually you pull out your lucky quarter and give it a flip to choose your direction — heads it’s Red Rock, tails it’s Treasure Island, and for some reason there’s no way this solution is going to choose Blackaller. You wouldn’t recognize that initial mistake until hours later.

Happily, once you start, you see some pretty well-respected sailors near you. Somehow they work their way ahead of you, but at least you know you’re headed in the right direction. Right? Over time it gets lonelier and lonelier on the course, but fortunately a large wind hole ahead allows you to rejoin your lost companions.

As the light fades, you recognize that dinner will be over by the time you get home and probably nobody else is going to finish the race either. So why should you stay out there if, in the end, everyone is going to pack it up and head home anyway? When you get back to the dock it’s packed with other early retirees who all console each other, recognizing that no one’s going to finish and we’re all wise to get back to the dock while there’s still some light. You also notice the flag that was drooping upon arrival is now showing a little life as it starts to flutter in a slightly building breeze.

As Sunday morning dawns you figure you might as well check the long list of DNFs just to confirm that nobody actually finished. You try to hide your surprise. This is where the humility comes in. Forty boats have finished. They are mostly all the very good sailors who sailed away from you early on. Nothing threw these people off their game. These sailors somehow navigated the crapshoot, wild cards and obstacles to finish and win another frustrating but fun Three Bridge Fiasco. Our hats are off to this year’s ‘lucky’ winners.

Once again reality and humility collided, forcing us to put our visions of glory safely away. Until next year.

More Lessons from the Fiasco

Despite what many would find a frustratingly light breeze, many find it’s still better than a day ashore. A couple of those were Cinde Lou Delmas and Milly Biller who, despite finishing 30 seconds after the 7 p.m. time limit, celebrated and memorialized a great day on the Bay aboard the Alerion 38 Another Girl with this video recap:

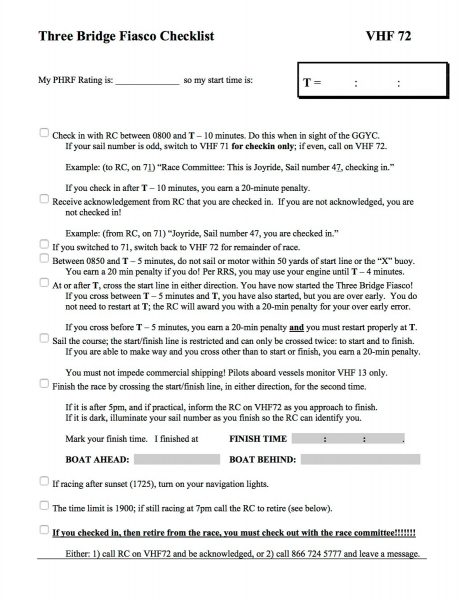

The other lesson is a “bravo” to the race committee for providing a helpful pre-race checklist. With a reverse handicap start, two radio channels for check-ins, and other details that we often miss, it was helpful to have their handy checklist ahead of the race. We might just remember to create our own in the future.

We salute the 40 boats out of 317 entered who finished before the time limit. And applaud the perseverance of those who missed finishing by seconds or minutes.

In the spirit of the Fiasco, the Bay Area Multihull Association has announced that, for the 2020 Doublehanded Farallones race on Saturday, March 28, competitors may round SE Farallon Island in either direction. You can enter here.

KKMI Rigging 101 Seminar

Bay Model to Begin Debate About Future Growth

On Wednesday, the US Army Corps of Engineers will hold meeting to discuss the master plan for the Bay Model — a process that began over a year ago and is coming to a conclusion. The public meetings will take place on Wednesday, February 12, at 2 and 7 p.m. at the Bay Model Visitor Center, located at 2100 Bridgeway.

Discussion of the Bay Model comes during the city of Sausalito’s ongoing three-plus-year debate of its own master plan, though the two processes are not related.

A master plan is a community or facility’s vision for future growth; that vision eventually becomes a blueprint followed by a set of laws guiding development. The decisions made in the master plan process help shape the way a city evolves into the future. Will there be a working waterfront, or will there be postindustrial coffee shops and breweries?

Located in the Marinship, the Bay Model has become a hub for Sausalito’s working waterfront, and the home of Matthew Turner, one of the world’s newest tall ships. “A lot of people say [Matthew Turner] symbolizes the waterfront and the sense of community,” Alan Olson, the project director for the Sausalito-based nonprofit Call of the Sea, told us in February’s feature story, The Future of the Marinship — Sausalito’s Working Waterfront.

“I had this byline when we started the project: ‘Building a ship, Building community.'” Olson said that community was about more than just getting the Matthew Turner built; it was also about sustaining the longevity of the vessel, “and providing powerful learning experiences under sail for all.”

The 2020 draft master plan and draft environmental assessment for the Bay Model are currently available at their website: www.spn.usace.army.mil/Master-Plans/. “Click on the links in the right-hand column titled ‘2020 Public Review Draft Master Plan’ and ‘Appendix B: Environmental Assessment’ to access the PDFs,” the Corps of Engineers said. “Hard copies of the draft master plan and EA are also available at the Sausalito Public Library and the Bay Model.”

Comments on the draft master plan and EA can be emailed to: [email protected]. The public comment period runs from Feb. 3 to March 3, 2020. “Master Plans are developed with every Corps project and the public is encouraged to provide input,” the Corps said. “The plans guide the use of resources for recreation and other purposes and are written to include future possible developments on public land with the goal of ensuring sustainability.”

For more information, you can contact: Brandon Beach, 415-503-6958, [email protected], or Christanne Gallagher, BMVC Park Manager, 415-289-3009, [email protected]

Correction — We originally said that Bay Model was about to hold the first of a series of meetings. In fact, Bay Model’s master-plan process has been ongoing for nearly a year.

Far-Flung Pacific Cup Entries

From humble beginnings 40 years ago, the Pacific Cup yacht race has grown into an event that attracts top-tier sailing talent from not just the San Francisco Bay Area but from all over the United States and beyond. In the record-setting 2016 race, Jens Kellinghusen’s globe-trotting Ker 56 Varuna VI showed up from Germany and blitzed to Hawaii in less than six days. Two years later, the well-traveled and syndicate-owned Mills 68 Prospector from the East Coast sailed the fastest elapsed time and claimed the overall win.

In 2020, more than 60 yachts are preparing to leave their mark on the race. The appeal of sailing to Hawaii is attracting boats from all over the West Coast, the Midwest and overseas. A number of boats from Southern California make the multi-day journey up the coast to San Francisco for the Pacific Cup. This year we see a surge in Seattle and Pacific Northwest boats planning to journey down to the Bay to take part.

Pacific Northwest

Marek Omilian of the Seattle-based TP 52 Sonic has recruited navigator David Rogers from the 2019 Transpac overall winner Hamachi and a host of talented Pacific Cup race veterans. With 2018 Pac Cup veteran Alex Semanis of Ballard Sails onboard as a watch captain and sailmaker, no stone is being left unturned in tricking out this former Med Cup boat with an inventory of sails to cover all the wind speeds and angles.

Michael Schoendorf’s distinctive Paul Bieker-designed Riptide 41 Blue rates with and races against 70-footers. Blue couldn’t quite sail to her rating in the relatively light conditions of 2018. If the breeze is up in 2020 and the speedster can live on a full plane, Blue could surf her way to the top of the rankings.

A couple of Pacific Northwest sleds are also champing at the bit to lay down quick tracks to Hawaii. Former race record-holder Rage, Dave Raney’s Wylie 70 from Portland, will return after sailing in the 2018 race. Another Portland-based 70-footer, the Santa Cruz 70 Pied Piper, has also entered.

Also from the Northwest comes a group of ‘30-something’ J/Boats. Karl Haflinger’s Tacoma, Washington-based J/35 Shearwater returns for her third consecutive Pacific Cup, but her first as a doublehanded entrant. After a humbling race during the crew- and gear-breaking 2016 race, Shearwater came back in 2018 and delivered a hard-earned thumping of the competition to take divisional honors in the Weems & Plath B division against a group of larger racer/cruisers.

Although they’ll race in different divisions, Shearwater should have a good battle against Chad Stenwick’s fully-crewed The Boss. Another Washington-based J/35, she’ll make the trip down for her first Pacific Cup. After sailing in the Victoria to Maui race in 2016 on a friend’s boat, Stenwick opted to buy his own boat and recruit some of his old crewmates to give it another go. Having already sailed a Vic-Maui, the crew was intrigued to tackle a new adventure.

The Boss and Shearwater will likely have their work cut out for them. Boats in this size and rating band have a high number of entries in the Pacific Cup, including another fully-crewed Seattle-based J/35, Jason Vannice’s Altair. Tolga Cezik of the Seattle-based J/109 Lodos told us that they’re looking forward to this Seattle showdown across the Pacific. “We are stoked to race against several other local Puget Sound boats in the same rating band, hopefully enjoying warm sunshine from start to finish. We can almost taste the mai tais already!”

A cruisier entry from the Evergreen State is Steve and Sherri Smolinske’s Bellevue-based Spencer 1330 True Love. They brought her back to life after 20 years of criminal neglect. A longtime group of friends and family will be sailing together after many other offshore races on a variety of boats. This will be the first big offshore race for the crew on True Love, recommissioned in 2018 after a four-year restoration. Among the crew are three couples and a father-daughter combo.

Midwest

International entries come from as far away as Switzerland and Japan, while David Herring’s Islander 36 Galatea is being trucked all the way from Wisconsin. A native San Diegan who’s always dreamed of sailing to Hawaii, he and his crew — veterans of several challenging Trans-Superior races — have decided to come out West and try their hands at a long ocean race.

SoCal

Another first-time entry, this one from Southern California, is Ian Sprenger’s Santa Cruz 27 Wilder. A lifelong sailor who grew up in Sausalito dreaming of the Pac Cup, Ian had to put his dream on hold for 13 years while serving in the Navy. As soon as he got out and started his civilian job as a pilot, he grabbed a good mate and began preparing for the race. ‘Wilder’ is a good name for the disposition of anyone who chooses to doublehand a small ULDB to Hawaii.

Doug Baker’s Long Beach-based Kernan 68 Peligroso has to be the fleet’s scratch boat and favorite to claim the fastest elapsed time. With a timeless hull form, a proven pedigree and no shortage of speed, Peligroso is a veteran of multiple Hawaii races. She’s sporting a highly experienced and very pro’d-up crew.

We wish all of these out-of-town boats — as well as the locals — the very best of luck in the 21st running of “The FUN race to Hawaii.”