Golden Globe Sailors Rescued

As we reported on Friday, a severe Southern Ocean storm, with winds to 70 knots and seas to 49 feet, resulted in the rolling and dismasting of two solo sailors competing in the old-school-style Golden Globe Race.

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

Irish sailor Gregor McGuckin suffered only minor injuries, but Indian sailor Abhilash Tomy was severely incapacitated and suffering. Tomy’s initial message to GGR HQ was: "ROLLED. DISMASTED. SEVERE BACK INJURY. CANNOT GET UP." Subsequent messages over the weekend were: "ACTIVATED EPIRB.CANT WALK.MIGHT NEED STRETCHER," and, "CAN MOVE TOES. FEEL NUMB. CAN’T EAT OR DRINK. TOUGH 2 REACH GRAB BAG," and "LUGGED CANS OF ICE TEA. HAVING THAT.VOMITTING CONTINUINGLY. CHEST BURNING."

Tomy’s remote location, 1,900 miles southwest of Perth, Australia, made rescue a challenge. As a matter of fact, the closest vessel to him was McGuckin’s dismasted Hanley Energy Endurance. But McGuckin put together a jury rig and proceeded, at 2.2 knots, toward Tomy.

Fortunately for the rescuers and rescuees, the storm had passed and conditions were favorable: 15-20 knots of breeze, 6-ft sea swells and good visibility. On Sunday, the French fisheries patrol vessel Osiris reached Tomy’s yacht, and her crew boarded Thuriya from Zodiac inflatable boats to administer immediate first aid and assess his condition before successfully transferring him to the ship. The Joint Rescue Co-ordination Centre in Canberra, Australia, which coordinated the rescue, reported: "Tomy is conscious, talking, and onboard the Orisis. Australian and Indian long-range P8 Orion reconnaissance aircraft are circling overhead. Thuriya’s position is 39° 32.79S and 78° 3.29E."

© Latitude 38 Media, LLC

Faced with a 1,900-mile sail across the Southern Ocean to Western Australia under a small jury rig without an engine (his fuel was contaminated when the yacht capsized), McGuckin accepted a rescue as well. The crew from Osiris picked him up and reported him to be "well and in good spirits."

Osiris is now en route to the isolated île Amsterdam, a day away in the middle of the Indian Ocean. (Try going to Google Maps and see how far you have to zoom out to see any substantial land mass!) From there one option is to transfer them to the Australian frigate HMAS Ballarat, due to reach the island in 72 hours, for transportation to Australia.

We wish both sailors a speedy recovery from their trauma. Look for more on this story in Sightings in the October 1 issue of Latitude 38.

Two Sailors Rescued Off Half Moon Bay

Two sailors were airlifted by the Coast Guard off their 37-ft sailboat yesterday almost 80 miles southwest of Half Moon Bay. "The two boaters aboard the sailboat Annie contacted the Garmin Emergency Operations Team through their GPS device, reporting their vessel was adrift after sustaining damage during multiple storms," a Coast Guard press release said. "They needed assistance and were experiencing rough weather and minor injuries."

The Coast Guard said that Garmin Emergency Operations contacted them at 7:15 a.m. yesterday, asking for help. A C-27 plane was dispatched to find the boat and assess the weather before a helicopter arrived and deployed their rescue swimmer. Not long after, the swimmer and two sailors were in the water, then hoisted aboard the helicopter.

"This case was my first as aircraft commander in San Francisco and was extremely challenging based on the complexity of being 77 miles offshore, the lack of communication with the sailboat and six- to 12-foot seas on scene," said Lt. Katherine Voth, the aircraft commander based at Air Station San Francisco who was onboard the helicopter. "We really appreciated having the C-27 from Air Station Sacramento on scene to provide weather and updated position reports and the coordination between Sector San Francisco and Air Station San Francisco watchstanders. This case was a Coast Guard team effort from start to finish that resulted in the rescue of two survivors."

Like other recent offshore rescues, the vessel was apparently left adrift at sea.

Waypoint Richardson Bay

Richardson Bay has long been a crossroads for all kinds of sailors. This week Clan VIII has joined other Richardson Bay anchor-outs while passin’ through on her way south.

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

The 148-ft Perini Navi steel yacht was launched in 2011 for Betram R.C. Rickmers, an entrepreneur and the fifth-generation owner of the German shipping company Rickmers Group, which is based out of Singapore. Clan VIII was designed by former Bay Area sailor/naval architect Ron Holland, who recently launched his new book, All the Oceans — Designing by the Seat of My Pants.

Clan VIII‘s mast is about 170 feet, giving her 50 feet of clearance when she sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge. She has a draft of 12.8 feet with her centerboard up, and 29 feet with the centerboard down, which would certainly explain why she moors so far out on Richardson Bay. Her upwind sail area is about 10,000 square feet, which is pretty large compared to the 424-square-ft sail area of a passing Bird Boat #21.

Clan VIII is apparently available to charter for up to seven guests with six crew for $150,000 per week, not including expenses and tip.

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

When you take advantage of the fine fall days of sailing on San Francisco Bay you never know who you might spot finding sanctuary in Richardson Bay.

* We mistakenly identified this boat as a Freya 39 but, thanks to reader Steve Saul, we now know it’s an Alajuela 38. Thanks Steve.

The New New England, Pt. 1

As readers of ‘Lectronic likely know, some Latitude staff have ties to the East Coast. Our publisher makes an annual pilgrimage to Maine, but Latitude’s newest editor also has New England roots.

I moved from San Diego to York, Maine, in 2001, and over the next four years, got to know New England through sailing, surfing, snowboarding, and simply being there through the seasons, in all their glory and grind. It’s an experience that I would recommend for every Californian, especially sailors. Last week, I was back in New England for the first time in three years, and was a bit stunned by how much it’s changed.

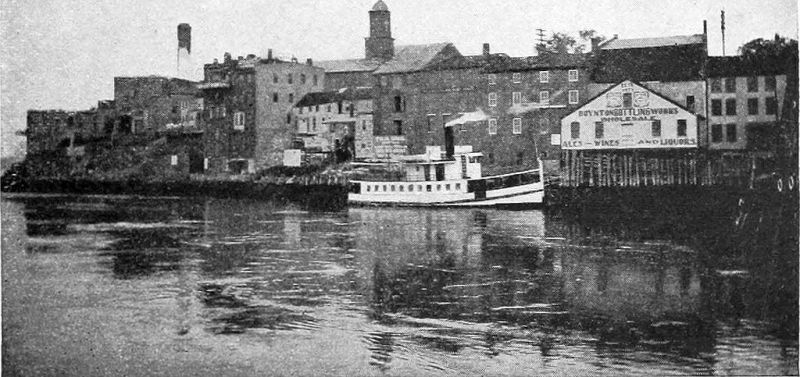

Just 20 minutes from York lies Portsmouth, New Hampshire, a picturesque town nestled against the Piscataqua River, which separates the Granite State from Maine. Thirteen years ago, Portsmouth was a relatively sleepy town. Like much of the “Sea Coast,” it certainly had its touristy side, but was affordable and felt like a homey place for locals, many of whom worked in the service industry. You could always find parking (and most of it was free), it was $4 for a pint, and a young, hardworking couple could afford to buy a house.

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

Now, there are parking meters everywhere (and parking at peak hours has become impossible), many of the cherished dive bars have been replaced by chic, craft-brew-slinging establishments, and there are hordes of hipsters and antique-hunting retirees roaming the streets. My local friends told me that they rarely went into town and were put off by all the new condos, trend-setting youth and other affectations of change that make a once-familiar place seem distant and foreign.

But we don’t believe in “back-in-my-day” stories at Latitude. As we talk about the changing demographics of the Bay Area and the world at large, we simply try to note the change taking place, and assert our values about what type of world we want to live in and what it should look like — namely, that people are sailing. Nostalgia will not save you, nor keep you anchored to a time when everything seemed perfect. The world will move on, with or without you.

I can’t definitively call Portsmouth a “cruisers” town, but while drinking rum punch on the (now ultra-touristy) decks along the Piscataqua, I saw a few tiny inflatables powering through the hefty current gurgling between Maine and New Hampshire. Portsmouth has two new bridges connecting the two states. The ancient World War I Memorial Bridge was recently replaced by a newer version, as was the Sarah Mildred Long (or Bypass) Bridge, which is just upriver, and was also recently rebuilt. A quick drive across the Memorial Bridge puts you in Kittery, Maine, where, as we wound along the coast, there were an astonishing number of sailboats on the hook.

Flocks of boats out of their slips and nestled in a picture-perfect cove was truly a sight to behold. The state of cruising in New England, by my extremely unscientific calculation, seemed quite healthy — although the exquisiteness of the area has, of course, long been known. “The best way — in keeping with the wildness of the [Maine] coast — to explore is under sail,” wrote Susan Butler in the New York Times in 1983. “And the very best time of the year to do it is in September, just after Labor Day. There is, historically, less fog than in the summer months, school has started, the crowds have gone home and the harbors and coves are as deserted as they ever will be while the weather is warm. For days you can sail, it seems, alone. Hours, a whole morning, can go by without another cruising boat in view.”

Thirty five years later, we certainly wouldn’t call the harbors and coves we saw “deserted,” nor can we imagine any length of time without another boat in view. And even in 1983, New England was struggling with what it wanted to become. “There are towns on the Maine coast, of course, tourist towns, but they differ in degree and size from those in more populous, gentler climes; fishing villages are more the norm,” Butler wrote in the Times. “Even the charming but busy (by Maine standards) town of Camden [two and a half hours north of York], for instance, with its antique stores, restaurants, inns, windjammer cruises, is looked at askance by many of its neighbors.”

Butler quoted cruising authority Roger Duncan, who would go on to write A Cruising Guide to the New England Coast. “‘Having seen what happened . . . to Camden, Stonington people are in no hurry to promote tourism.’ Everywhere Down East there is a genuine helpfulness about the people, but also a deep reserve, a feeling of ‘respect me and I will respect you.’ A feeling of privacy.”

Stay tuned for the next installment of the New New England. And if you’re from the East Coast — or a place that’s experiencing its share of change (i.e.: everywhere) — we’d like to hear from you.