A Cautionary Tale

As we were motoring out of the San Rafael Creek yesterday, we noticed a boat — maybe 35- to 40-ft — anchored just outside the channel markers. This was curious, as the San Rafael Canal is notoriously (although shockingly) shallow, especially where this boat had dropped the hook.

©2018Latitude 38 Media, LLC

It was about 1:30 p.m. and approaching max high tide, and we thought that perhaps the boat, which likely strayed from the channel upon approach or departure, was waiting for the top of the flood to make her escape.

©2018Latitude 38 Media, LLC

But upon our return at about 5:30, the boat was slumped over on her keel. In an upcoming feature article about San Rafael sailing, we’ll talk about the perilously shallow entrance to San Rafael Creek, and what the future of this neglected waterway might be.

©2018Latitude 38 Media, LLC

PS: We don’t mean to cast any judgment on the boat in question. Even with our three-foot draft, we’ve run aground going into and out of the Creek more times than we care to admit.

If you have any knowledge of this boat, or have a story to share about San Rafael Creek — or would like to make a plea for its dredging — please let us know.

Vestas Ready to Rejoin Volvo Race

Six weeks after crashing into a fishing boat and killing one fisherman in the crowded waters of Hong Kong, the Vestas/11th Hour Racing Volvo 65 is repaired and back in the water. The boat had been shipped to New Zealand for repairs following the collision just prior to the finish of Leg 4, at 1 a.m. on January 20. It launched today in Auckland, with a test sail scheduled for later this week.

"It’s been an amazing effort by all involved to get the boat back in the water," said American skipper Charlie Enright, 33. "A month ago we said we’d be back on the water on this day, and we’ve stuck to the schedule. It’s amazing."

The team and the Volvo Ocean Race organizers have been circumspect in discussing the collision, but the Vestas skippers have opened up a bit more about that night. Enright was not aboard at the time. Mark Towill, 29, was skipper for Leg 4. Enright sat it out due to a family crisis. During Leg 3, from South Africa to Australia, Enright’s 2-year-old son had been admitted to the hospital with a case of bacterial pneumonia. "There comes a point when family is more important than the job you’ve been hired to do and I was at that point," said Enright. "I did what was best for my family." Immediately before the end of Leg 4, Enright traveled to Hong Kong to greet the crew at the finish line, but instead wound up playing an active role in the crisis management process from shore.

“I have been asked if it would have been different if I was onboard. Definitely not,” said Enright. “The crew has been well trained in crisis situations and performed as they should. They knew what to do and I think they did a phenomenal job given the circumstances. The team was engaged in search and rescue for more than two hours with a compromised race boat,” Enright said.

“I’m very proud of our crew. We were in a very difficult situation with the damage to the bow, but everyone acted professionally and without hesitation,” added Towill. Both skippers expressed their condolences to the family of the fisherman who did not survive that night.

Despite the badly damaged bow, Towill and the crew of the stricken raceboat carried out a search and rescue effort. Ten fishermen were retrieved from the water. The one who died was transferred to a helicopter with the assistance of the Hong Kong Maritime Rescue Co-ordination Centre.

A new port bow section was laid up over a VO65 hull mold at Persico Marine in Italy and then sent to New Zealand, where it was spliced to the hull of the team’s VO65 in the past two weeks. East Bay resident Bill Erkelens Jr. is the team manager and received high praise from Enright and Towill. Erkelens had put together Enright and Towill’s program in the 2014-15 Volvo Ocean Race, and he was the first person they hired for the current team.

Leg 7, 6,700 miles through the Southern Ocean and around Cape Horn to Itajaí, Brazil, is scheduled to begin March 18.

For more details, see www.vestas11thhourracing.com and www.volvooceanrace.com.

Another T-shirt Winner

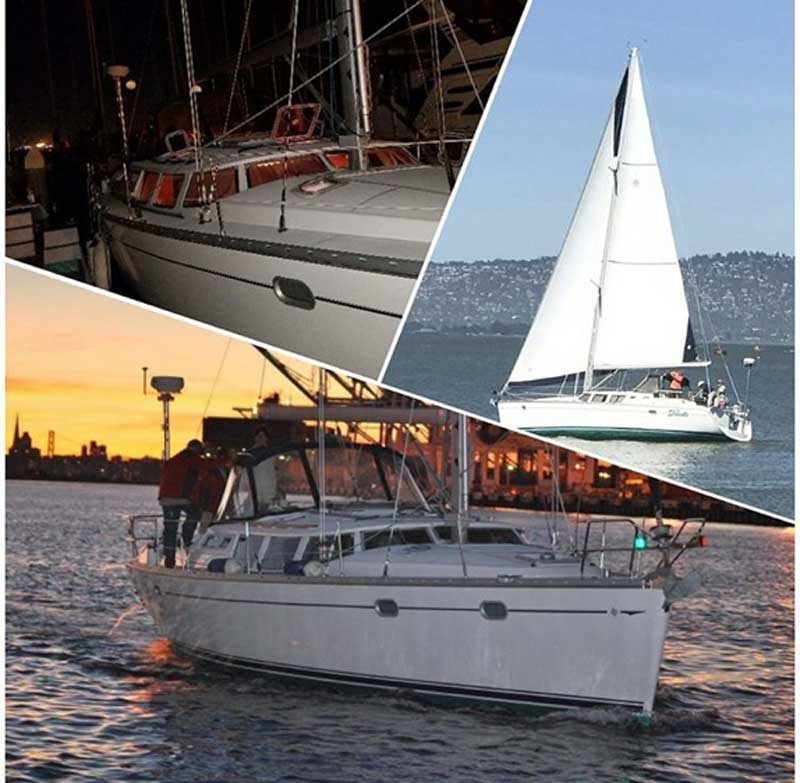

Kevin Connolly came to the Bay Area in 1978 and is a seasoned sailor. He’s owned a couple of boats, his first being a Nonsuch 30 named Cariboo (though technically he owned a Hobie Cat before that). Kevin said he’s been reading Latitude 38 for 40 years – which finally paid off when he opened last month’s issue to discover that he had won a Latitude 38 T-shirt! Since around 2002, Kevin has crewed regularly on Slainte, a Jeanneau Deck Salon 43, every Sunday out of Marina Village in Alameda. Slainte means "cheers" in Gaelic.

Kevin’s brother, John Connolly, who passed away several years ago, owned Modern Sailing Academy in Sausalito and was well respected for dedicating much of his life to sailing education. John personally led more than 16,000 miles’ worth of coastal trips from San Francisco Bay to Monterey and back. In addition to teaching locally, John was known for teaching advanced ASA courses in overseas locations.

Kevin’s favorite part about sailing in San Francisco Bay? “The wind and the beautiful vistas — they never get old.”

Keep your eye out for those golden tickets in the March issue of Latitude 38, and for Slainte sailing the Bay.

Extended Interview: Carter Cassel

We first met Carter Cassel — the skipper of San Francisco’s National Historic Landmark ship Alma — at Summer Sailstice last June. We’d heard that Cassel comes from a serious sailing family. Curious, we met up with him last month at the San Francisco Maritime Museum, and wrote about him in the March issue’s Sightings.

There’s far more to Carter Cassel than 750 words allow, so we’re bringing you an extended interview. Plus, Cassel asked if we could mention two of his biggest influences, saying he wanted to give credit where credit is due. "Ian McIntyre and Alan Olsen, both legends in the schooner trade and local heroes, were extremely influential in my early career and gave me my big breaks, or rather, gave me the chance to sink or sail."

©2018Latitude 38 Media, LLC

Cassel said that after considering a ‘fast track mariner career’, he committed to working on traditionally rigged vessels. "And when it’s all said and done, I feel pretty fortunate. I’m still doing what I learned how to do when I was a kid. A lot of my peers, they’re not because in this industry, the money in the sail-training and traditional-rig world isn’t what it could be, but you still need the same license as the commercial guys. And everybody ends up finding something else to do when they want to raise a family. I was the same way. I followed my predecessor, Ian McIntyre, who taught me about traditional-rigged vessels and operating square-rig vessels. He used to run the Hawaiian Chieftain.

"Long before the Chieftain was run by [Grays Harbor Historical Seaport], it was Ian’s brainchild to do these education programs. It was a way he could keep running, and keep the boat busy in the off season. He turned it into a pretty amazing program that we actually mirror on Alma as well, and some other programs like Call of the Sea also templated their programs off of what Ian started."

"But I mention him because of any of the sailors I know, Ian should deserve to be doing this thing. But he’s in the building trades now; he’s got a family, and I actually resigned to do the same thing after working on commercial ship-assist tugs in the Bay. I swallowed the anchor, went into the building trades, and started swinging a hammer for my same mentor, Ian. What a shocker it was to be at the bottom of the barrel again, in order to be home to my family at night."

Carter likened working construction to working on a boat, where sailors must be a jack of all trades. He said that he eventually had the "fortunate opportunity to help build the Oracle cats at pier 80 . . . which I quit in order to land this dream job [as captain of Alma], which I had to compete for and win twice; but that’s a whole other story."

As we reported in Sightings, Cassel said that thousands of kids come aboard Alma every year. "And all it takes is one of those children to grow up to do something that’s significant and then give back to funding and the longevity of a boat like this. An outfit that does that really well is the Sea Education Association [SEA]. They take college-level students that don’t have to have any sailing experience and put them on a boat. It’s just a semester program; it used to be heavily marine-science based, so you’d basically be proving a science thesis while you were out at sea — but it’s changed since then."

©Latitude 38 Media, LLC

"These guys have never been on a boat, and they’re having this profound experience. Some of them might keep sailing, some of them might not, but all of them become successful in their lives and they always give back to the program, so it really has a tremendous kind of endowment in that way. That, to me is a good sign of how inspiring being on a boat like this can be [we were standing on the deck of Alma at dusk on a gorgeous February day]. I’ve always been proud of harboring this sailing knowledge, working these older vessels, and the skills it takes to get Alma upwind or downwind, you know? It’s something I take pride in, having these skills and knowledge."

Were you ever part of a sail training program? Do you know someone who was, and who sings its praises? We’d like to know.