Capsize at Cape Horn

While much of the sailing world has been focused on François Gabart and his incredible round-the-world record attempt, it’s been easy to overlook fellow French multihull sailor Yves le Blevec. The skipper of the Ultim’ trimaran Actual, le Blevec left France on November 24 to embark on a similar — though very different — voyage. Attempting to set a new world record the ‘wrong way’ around the world, Yves’ planned route was to descend the Atlantic, then turn right at Cape Horn and continue westward — as opposed to the more traditional eastward downwind romp through the Roaring Forties and the Southern Ocean.

Unfortunately for Yves, he capsized just after rounding Cape Horn, sailing upwind, when a crossbeam broke. Sailing hard upwind on a starboard tack, allegedly with three reefs in the mainsail and a small jib, Actual broke in 50+ knots of Southern Ocean breeze and seas to 20 feet. When the beam broke and the hull went from vertical to horizontal, the big tri went over, likely similar in many respects to the ill-fated Artemis Racing AC72’s structural failure and capsize in San Francisco Bay in the lead-up to America’s Cup 34. Fortunately for Yves, he was unharmed during the ordeal and remained calm while waiting for rescue. A cruise ship, the Stella Australis, diverted course to the scene to intervene if necessary, while Yves was eventually plucked from his overturned trimaran by a helicopter from the Chilean coast guard.

Actual (formerly Thomas Coville’s Sodebo) is a sistership to Sidney Gavignet’s old Oman Air Majan that suffered the same fate in 2010 when a crossbeam broke, sending the boat over. Actual’s third sistership is Francis Joyon’s old IDEC 2, which set many world records including the solo, nonstop record which was just broken last year by Thomas Coville on Sodebo Ultim’ (that record should fall this weekend to François Gabart). The design of these boats, penned by Nigel Irens and Benoit Cabaret, is long, lightweight and skinny by today’s standards. For her 100-ft length, she’s just 54 feet wide and weighs just 11.5 tons, compared with the new breed of VPLP trimarans, which are 70+ feet and weigh 14.5 to 15.5 tons. This writer isn’t a naval architect, but in a world where width = righting moment and stability, we can see why a skinny design would help this boat go the way of the dinosaur.

The Actual team is organizing efforts to attempt to salvage the boat, but with the nature of the damage, her geographically distant location from the team’s base in France, and a design that has been left behind by modern yacht design, one must question if the potential reward is worth the effort.

For those keeping score at home, two-time Vendée Globe podium finisher Jean-Luc Van Den Heede still holds the solo, westabout circumnavigation record with a time of 122 days, 14 hours, 3 minutes, set in 2004 onboard a monohull named Adrien.

Get Ready for a Windy Weekend

After weeks and weeks of placid 5- to 10-knot conditions, the Bay is about to do its best impression of summer, only colder. So if you want to avoid midweek traffic, go sailing.

©Latitude 38 Media, LLC

Are you excited by this forecast (finally some wind!), or does this put a damper on your plans for a slow-and-leisurely, chardonnay-sipping sail? Here’s your weekend forecast, courtesy of the National Weather Service (and if you do go out this weekend, please send us some pictures):

Today

N winds 10 to 20 kt with gusts up to 25 kt, becoming NW 20 to 30 kt this afternoon. Wind waves 3 to 4 ft, increasing to 4 to 6 ft this afternoon. W swell 7 to 9 ft at 16 seconds.

Tonight

N winds 30 to 35 kt with gusts up to 45 kt. Wind waves 10 to 15 ft. W swell 6 to 8 ft at 15 seconds.

Sat.

N winds 25 to 35 kt with gusts up to 45 kt. Wind waves 10 to 15 ft. NW swell 6 to 7 ft at 14 seconds.

Sat Night

N winds 25 to 30 kt with gusts up to 40 kt. Wind waves 8 to 11 ft. NW swell around 5 ft at 13 seconds.

Sun

N winds 20 to 30 kt with gusts up to 40 kt. Wind waves 7 to 10 ft. NW swell 4 to 5 ft at 13 seconds.

Sun Night

N winds 20 to 30 kt. Wind waves 4 to 7 ft. NW swell 3 to 4 ft at 15 seconds.

A Latitude Far, Far Away

In honor of the release of Star Wars, Episode VIII today, we wanted to share a story from Howard Macken of Sutter Sails, who wrote the following for the September 1983 (Vol. 75) issue of Latitude 38. It’s easy to forget that Star Wars has its roots in Marin County, and, for one movie, employed a bevy of notable Bay Area sailors.

It was 2 a.m., the wind was blowing a good 25 or 30 mph as I stood on the poop deck looking forward. The men on the deck below were working furiously bending and furling the massive brown sails. The vision conjured was that of a Spanish galleon running before a squall. But instead of spray stunning our faces, it was sand. Sand in our mouths and sand in our hair. The ocean on the far, far horizon was not water, but desert. There were sand dunes as far as the eye could see on this moonlit night.

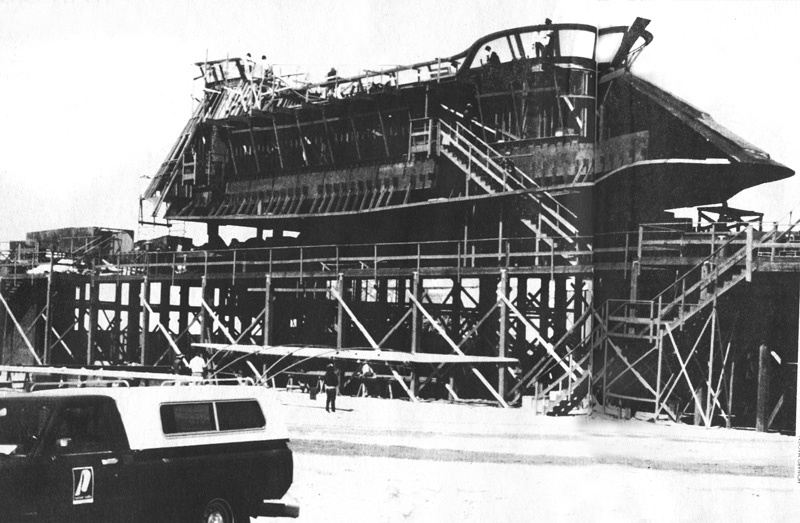

Well, actually it was. We were on the deck of Jabba’s Barge, 100 feet above the desert floor, on the planet of Tatooine.

It all started back in February 1982, when I stopped by Bill Kreysler’s new shop in San Rafael. Since the demise of Performance Sailcraft (which used to make Lasers and J/24s), Bill had taken over some of their space and was doing custom fiberglass and mold work. He’d just signed a contract to build some fiberglass panels for Revenge of the Jedi (later named Return of the Jedi). I jokingly asked if they needed any sewing done, and Bill said they were building some kind of barge in the sand dunes near Yuma, and that they might need some sails.

I didn’t take it too seriously until two weeks later when I received a call from Commodore [Warwick] Tompkins, asking to meet with me and discuss the Lucasfilm project. Actually, there were three of us at that first meeting: me, Commodore and Derek Baylis, a well-known local yachtsman and a consulting engineer. They were both excited over the proposal from Lucasfilm. Bill was in charge of organizing the construction of the mast, spars and sails for Jabba’s Barge, which would be one of the largest, most elaborate sets for Return of the Jedi.

And we at Sutter Sails . . . would build the sails.

In March, we had about a month to design the sails and ship them to Yuma. Luckily it was our off-time at the loft, and we devoted our full attention to the project. Six hundred yards of tanbark material was ordered from Walter Crump of Aquino Sailcloth.

The actual rig was to resemble a "Regalo schooner," with the two Regalo sails overlapped with the mast and kingspar higher than the fore. Each of the four sails had seven full-length battens totaling 250 feet. The longest were two-inch- square aluminum extrusions, and the rest were inch-and-a-half pultruded fiberglass.

The kingspars were ordered from Sparcraft, who had the largest sections available on the West Coast: a 14" oval by 70′ long. These were then tapered down at each end to 4". Victor Iron Works of San Rafael did the welding on the sqaure masts. Derek had devised a system whereby the whole rig would lower when not in use and raise when the sails were out and filming was in progress.

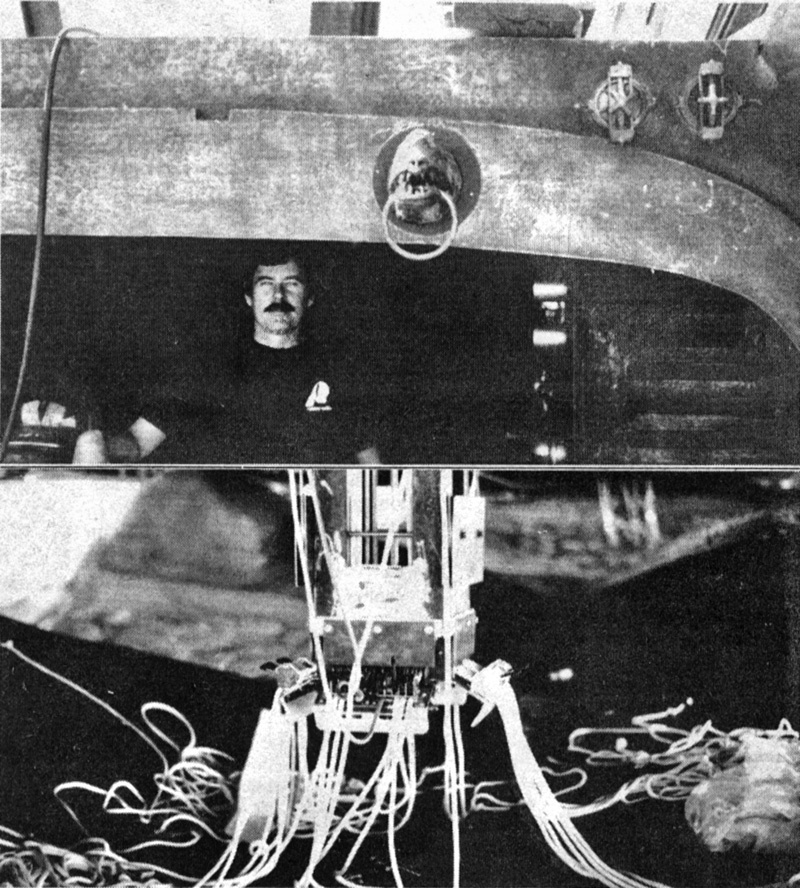

The act of raising and lowering the mast, and the "brailing" or furling of the sail, would be carried out deep in the bilge. At the base of each mast was a battery of sheet jammers, winches and blocks, not unlike many of the 12-Meters of the 1970s.

©2017Latitude 38 Media, LLC

All through March, our seamstresses Terry, Peggy and Sandra were busy at a yeoman’s (yeowoman’s?) job of stuffing all that heavy sailcloth through the sewing machines. The sails were all seamed and the batten pockets installed at the loft. But the sails had to be finished when the "clew" locations were known. This would be done on location in Yuma. Peggy Kashuba and I drove down to Yuma late in March with two machines, the sails, equipment and extra sail cloth. Louis Friedman, the unit supervisor at Lucasfilm, had set us up with a vacant dance studio to use as a makeshift loft. Sutter Sails Southwest was in business!

Seeing the set for the first time was a big thrill. The barge was an incredible piece of work (a cross between a galleon and the space shuttle). It was "hovering" beside the Sarlacc Pit, which didn’t frighten us at all: Indeed, we found it to be the coolest spot within a 50-mile radius for eating lunch.

We had the clew locations and began our marathon sessions behind the sewing machines. Bill, Derek and Commodore were all at the site trying to install the spar masts and rigging amidst the carpenters, painters, electricians and the ever-present art directors, who could decide to change everything at a moment’s notice.

Bending the sails was no easy task. The problem was the installation of the battens, which had to be put in the sails in two pieces, and then tensioned and bolted. All of this had to be done with the wind blowing, and with the rig high enough off the deck to make working very awkward.

©2017Latitude 38 Media, LLC

Commodore was in his element here, hanging in the bosun’s chair from a huge crane, directing the whole operation. When it was time to set the sails, we radioed instructions to the crew in the bilge and the huge sails were sheeted home. The aft two sails were set first, and with the wind increasing all the time, the decision was made to go for broke and set all the sails. An anemometer was rigged up on the aft kingspar and read in the bilge, then radioed on deck (it was blowing 20 to 25). Gusts could easily be seen approaching as large clouds of sand appeared on the horizon from a good mile away.

We all just stood there on deck, listening to the wind howling. We were waiting for something to give (it was now gusting to 35), but lo and behold, everything was as stable as a rock. Derek had done himself proud. My nightmares of the sails coming apart during filming were fading away.

It was now just three days away before shooting started, and we were finished. It was a great feeling for our crew of Bay Area sailors. We’d pulled it off in record time and done a first-class job to boot. Bill, Derek and I returned home with mixed emotions. It was good to be home and get some rest, but it had been an exciting two weeks, and we were sorry to miss filming.

Commodore and Peggy stayed with the Lucasfilm crew. Commodore supervised the furling and unfurling of the sails each day, and Peggy stayed in case my nightmare came true and emergency repairs had to be made.

It was an experience that none of us will ever forget It was thrilling to be involved, and to see first hand how it all came together to produce a movie. But working with the Lucasfilm people made it extra special. Their reputation in working with local businesses was affirmed and appreciated. They were dedicated crew who insisted on doing the job right with no compromises. We felt proud to have played a small part in their efforts.

This story has been edited from the original version.

Reader Submission: Where’s Whaledo?

We thought we’d end the week with another photo from Jan Passion, taken this summer at the height of humpback rush-hour traffic. Have a wonderful weekend, everyone.