Wanna Teach Sailing?

Three spots are open, wide open, for US Sailing Level 1 instructor training December 16-19 at Encinal Yacht Club in Alameda. With Northern California seeing shortages of certified Level 1 instructors (these are often college kids in summer jobs), your local clubs and community sailing leaders are trying to do something about it. US Sailing has stepped up, and this four-day program is part of the deal. Could there possibly be a better part-time or summer job for a young sailor?

©2017Latitude 38 Media, LLC

Don’t put it off, and if these three slots fill up without you, contact Kimball Livingston for the next steps.

The minimum age for Level 1 training is 16. After that, you can take it as far as you want. Here is a link to the details, and be advised, this may take a while to load. It’s a test to make sure you have enough patience to be a teacher.

40 Years of Mischief, Part 2

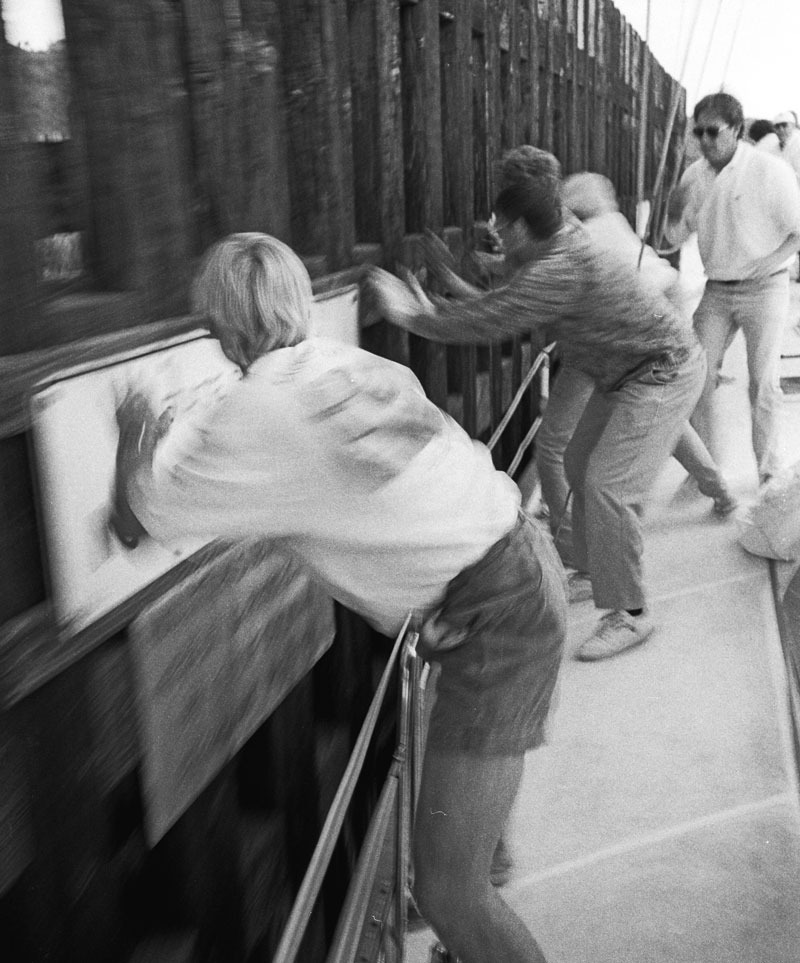

Back in the years BC — “before catamarans” — Latitude 38’s publisher owned a series of monohull sailboats. The biggest was Big O, an Ocean 71. One year, he decided to do San Francisco Yacht Club’s Midnight Moonlight Maritime Marathon, which starts in Raccoon Strait near the sponsoring SFYC in the afternoon, and finishes just outside the Strait whenever you get back from rounding the center tower of the Carquinez Bridge. The usual cast of thousands was aboard. Numerous beers later, we got to the bridge and there was such a hellacious ebb running that we couldn’t get around the damn tower piers. Tack after tack, we sailed waaaaay upwind, only to turn and get swept past it before we could get the big boat around. After getting passed by several smaller boats, the Wanderer sailed what seems like halfway to Rio Vista, turned, and commited. Everyone onboard was on pins and needles. "We’ll make it. No we won’t. Yes we will. No. Yes. No. Yes. Maybe. Maybe not. No. No freaking way!" The helm spun down to tack again but it was too late. We went head-on into the wooden pilings. To add insult to injury, the current then swiveled the stern around and mashed the port side against the pier. Big O dragged and scraped the whole way down the gnarly pier until she clears the pilings. The collision mangled the bow pulpit and anchor rollers, bent a few stanchions, and etched an array of battle scars on the topsides, but no one was hurt. A bit the worse for wear, we finally made it around in a few more tacks, and finished back in Raccoon Strait around 1 a.m. The damages put the boat in the yard for almost a month.

©2017Latitude 38 Media, LLC

One Saturday back in 1991 sometime, one of the editors borrowed the photo boat to take his mom and sister to Angel Island for the day. When they got back after biking most of the way around the island, the boat wouldn’t start. Apparently something had drained the batteries. (It wasn’t the first time.) You’re not supposed to leave a boat at the Angel Island dock overnight, but the rangers were accommodating in this instance. The editor promised to be back first thing in the morning to attend to the situation. Sunday morning, he returned on another boat, intending to tow the photo boat back to its berth and deal with it there. He later said, “As I was coming into the cove, I couldn’t see the boat. All I could see was this little white triangle in the slip where it had been.” The little white triangle turned out to be all that was showing of the bow, still tied to the dock. The rest of the boat had sunk. Oops.

©2017Latitude 38 Media, LLC

The story didn’t stop there. After being refloated, towed home, and then hauled out, the boat was put out to bid for new engines. A low bid was accepted, and it disappeared into the wilds of the South Bay, never to be seen again — well, for several years, anyway. A friend finally spotted it down some remote slough in Alviso or somewhere with the half-apart engines full of rust and rain. Turns out the low-bidder fellow doing the ‘restoration’ was serving time in prison. No wonder he stopped returning our calls. 38 Special was eventually evacuated to a legitimate yard, where it got two new engines at, let’s just say, a higher rate.

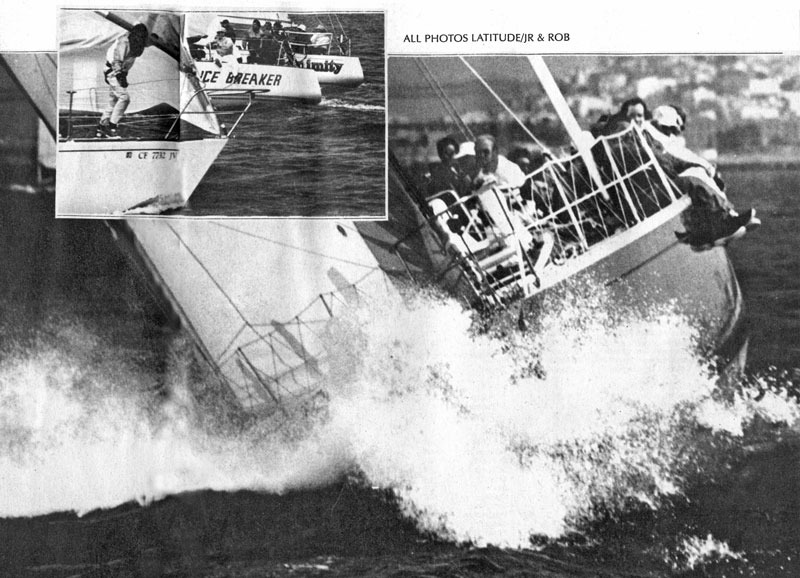

Among the many photo boats Latitude has murdered – uh, we mean utilized – over the years was an 18-ft Boston Whaler that we affectionately called the Boston Death Trap. It had some big old outboard on the back that worked fine until it didn’t. It developed the irritating habit of dying at the most inopportune moments possible. One of those moments was at the 1987 or ’88 Big Boat Series, one of the last attended by the maxi fleet. The photographer that day was looking for a nice bow shot, so he crossed in front — well in front — of the Holland 81 Condor, which was on a spinnaker run in fresh breeze. As soon as he got directly in front of Condor, that *&$# engine died. The maxis moved deceptively fast anyway, but Condor was on our editor so fast his life barely had time to flash before his eyes. “I dropped the camera and got ready to jump and hopefully grab the bow pulpit when they cut the Whaler in half,” he recalls. Fortunately, an alert helmsman saw what was happening and swerved at the last possible second. Condor’s bright red hull (and her pissed-off crew on the rail) passed within about two feet of the Death Trap. It was over as quickly as it had started and, as usual, the outboard started right up and ran fine again. Needless to say, our intrepid cameraman did not attempt any more bow-on shots that day.

©Latitude 38 Media, LLC

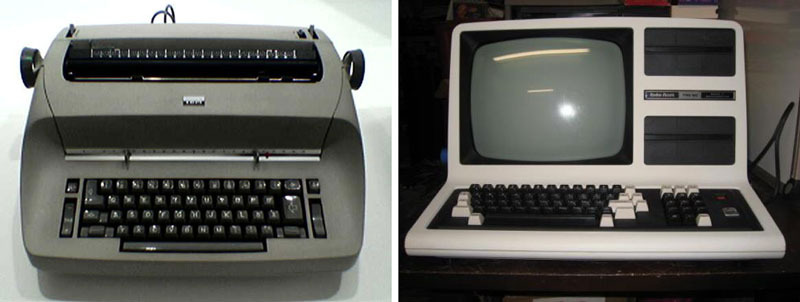

PCs were not in widespread use when Latitude first started out. Fortunately, electricity had been around for a while. For our first 10-15 years, all stories were created using IBM Selectric typewriters. Completed pages of copy were given to our in-house typesetter, Ellen, who typed every word into our big blue typesetting machine. Blue would make a series of R2D2-like grunts, whistles, whirrs and clicks — and out would come a continuous stream of column inches, which would then be cut apart, hot-waxed, and stuck onto a gridded piece of heavy paper the size of two facing pages, along with half-tone photos and captions. This is how articles (and ads) were put together — two sticky pages at a time. Everything from soup to nuts was done in-house except for the printing. Our first computers were Radio Shack TRS-80s, or ‘trash 80s’ as we called them. They were little more than glorified typewriters with a screen. But for the first time, we could go ‘directly’ from computer to typeset copy. This involved carrying one of those large, truly floppy discs upstairs, plugging it into another Trash 80 connected to the typesetter, going through a long, involved series of typed-in commands, sacrificing a chicken or other small animal, doing a modified war dance and selling our soul to the devil — again. If all went well and we didn’t miss a keystroke, copy would spit out. If not, Ellen was right there to save our butts — again. Okay, we’re kidding about the small animals.

December Racing Preview

It’s all pros aboard for the final act of the Extreme Sailing Series, but with many of our readers still in Baja California Sur after finishing the Baja Ha-Ha, some may wish to get into the act as spectators. The season finale of the series, sailed in foiling GC32 catamarans, will start tomorrow in Los Cabos and run through the weekend. The regular six teams will be joined by two wild card teams, one from the US and one from Mexico. Spectators can watch from the free public Race Village on Médano Beach. See www.extremesailingseries.com/events/view/los-cabos-mexico for details.

Those of us toughing out the chill of 50° temperatures in Northern California have plenty of midwinter racing to look forward to. Two series that start in December invite small boats to race at Richmond Yacht Club on the first weekend of the month and Lake Merritt Sailing Club on the second weekend of the month. (For info on LMSC’s Robinson Midwinters in Oakland, contact Peggy at 510-836-1805.) Most of the fleets in RYC’s Small Boat Midwinters will compete on the first Sunday of each month through March; Saturdays are set aside for the youngsters in Optis and the El Toro Green fleet. If you want a one-design start and trophies for your class in Sunday’s series, you must have five or more boats registered prior to 3 p.m. on Saturday, December 2. All other boats will sail in open class(es).

©Latitude 38 Media, LLC

Meanwhile, down south, San Diego YC’s Hot Rum Series will wrap up this Saturday. The popular three-race series has 139 boats entered, with Alec Oberschmidt’s R/P 50 Staghound leading the overall standings.

Armchair sailors needing a break from holiday hubbub may want to follow the 628-mile Rolex Sydney Hobart Race. It will start at 1 p.m. AEST on Boxing Day (December 26) in Australia — that’s 6 p.m. Christmas Day here in the PST zone. See www.rolexsydneyhobart.com.

Clipper Race News

It’s been less than one month since the Clipper 70 Greenings ran aground on the opening day of the Clipper’s Race 3. While the remaining 11 boat-fleet has now completed the race into Fremantle, Western Australia, the salvage operation to remove the monohull from Cape Peninsula is also now close to completion.

Following the incident on October 31, all crew were quickly evacuated from the yacht by the local rescue service, NSRI, with no injuries reported. After being contracted by the Clipper Race, Navalmartin promptly dispatched local admiralty expert and surveyor Peter Brinkley from Cape Town and instructed a salvage team to assess the situation.

Pollution control was of paramount importance. "The first task was to remove all the diesel fuel from the tanks," said Brinkley. "This was done quickly and no spillages occurred."

After reviewing the state of Greenings (CV24) over the following 48 hours, it was unfortunately decided that the vessel would take no further action in the Clipper 2017-18 Race, and subsequently that it was beyond repair and should be removed by salvors.

The removal contract was awarded to the Subtech Group/Ardent, which specializes in marine services, including salvage projects, throughout Sub-Saharan Africa. With an operating base in Cape Town, a team was quickly mobilized to work with the South African Maritime Safety Authority (SAMSA), the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) and the casualty management team to oversee the cleanup operation and wreck removal.

Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, the event’s founder and chairman, explained: “Once the assessment had been made that the vessel was not repairable, our aim was very clear; we needed to deal with the situation quickly with the priority of minimizing environmental impact and returning the beach to its original state.”

On the work that has been done over the past weeks, Peter Brinkley adds: “We faced a number of early challenges to the removal which included obtaining access to the beach, as it is in a very remote location; and also a bush fire started in the surrounding veld partway through the operation, which delayed efforts for a few days.

“It was a priority to work quickly; the varying weather conditions only gave us small windows of time to carry out the task at hand. Time was working against us. We had to deal with the incessant influx of sand at high water brought in by the breaking waves and exacerbated by bad weather. We have to deal with the added challenge that no vehicles would be allowed through the reserve to access or move the yacht.

“Subtech opted to erect a tower made of scaffolding material to support the mast before we could start cutting the hull up from the forward and aft sections, dismantling components onboard, and removing the engine. The removed hull pieces were transferred into cargo nets and loaded onto a truck for disposal.”

“We had some pretty big swells along the coast while the work was underway," continues Brinkley, "which did hamper the efforts significantly at times. At one point the waves reached four meters and battered the yacht, undercutting the scaffolding, which sank approximately 400 millimeters.

“The mast has now been lowered gently using the scaffolding tower. Only the keel and some of the bottom and port-side shell remain, and they are buried in the sand, however we expect these final parts to be removed in the coming days and the beach will then be restored. Much of the hull and deck gear has already been airlifted away from the site.”

Speaking about the loss of CV24, Sir Robin says: “She had completed two round-the-world voyages, one of which she was the winner, as LMAX Exchange, and had an unbeaten streak in the 2017-18 race. It’s always just desperately sad to see a fine vessel finish its story like this.”

A full investigation is currently underway into the reasons for the grounding, and the Clipper Race promises to publish the findings as and when they are available. The rest of the Clipper Race teams will all welcome various Greenings crew aboard to continue their remaining race legs.

Following the relief of getting to port after an incredibly tough and emotional leg, now officially known as the most challenging in Clipper Race history, the participants gathered for the prize-giving. First though, everyone joined together on the grass outside the Fremantle Sailing Club for a memorial service for Simon Speirs, who lost his life at sea during this leg. Led by a chaplain from the Mission to Seafarers, GREAT Britain round-the-worlder Tessa Hicks and skipper Andy Burns read words. Simon’s family provided a moving tribute read on their behalf.

The fleet will depart Fremantle on Race 4, the 2,500-mile race to Sydney, on December 2. See www.clipperroundtheworld.com.