Where’s Rimus . . . Now?

When Rimas Meleshyus didn’t show up anywhere in the South Pacific after he departed Hawaii in June, we feared the worst. This is how most stories about Rimas start.

The 66-year-old Russian immigrant left Hilo in his Rawson 30 Mimsy over four months ago. He had been in touch via satellite phone, until it broke somewhere near Fiji. No one had heard from Rimas in weeks, until the Coast Guard rescued him off Saipan — a US Commonwealth north of Guam — a few days ago.

"I’m emotional because long time I was out at sea," Rimas was quoted as saying by National Public Radio. "To sail from Fiji to north was very very difficult. Because the current pushes me all the time." Like most news outlets that interview him, NPR was quick to note that this wasn’t Rimas’s first rescue. Not even close.

"We all thought he was dead," said Rimas’s primary benefactor Jean Mondeau, who met Rimas 22 years ago in Guam. "The guy draws attention because he’s a train wreck. But he’s pretty harmless. He’s a very nice person and very polite. But he believes his cognitive ability is greater than it is. Rimas swears in his mind that he can sail, and that he’s the ultimate sailor."

In May 2016, Rimas — who is technically on a solo circumnavigation — was rescued off the Big Island, which landed him on the local news (in the file footage, he’s seen wearing his trademark striped shirt . . . and a Latitude hat). On that trip, Rimas had run out of food and water before he was finally picked up by the fire department after leaving Monterey 46 days earlier.

"But should he have been out on the open ocean at all?" asked Hawaii News Now, a question that some of us have been debating when reporting on the admittedly colorful vagabond who’s been rescued multiple times. Hawaii News Now cited a March 2016 rescue off San Francisco, a 2012 wreck off the Aleutian Islands, and a 2014 search that was launched after Rimas went missing, and cited one of the many times Meleshyus had to be towed into harbor.

"To this very day, he has never made landfall," Mondeau said, adding that Rimas can’t leave port either — he’s always towed into and out of harbors.

"What could possibly motivate such seemingly masochistic adventures," we asked in a 2014 ‘Lectronic, after Rimas had sailed 2,200 miles from Hilo to San Francisco in 56 days. In a word, freedom, we said. Rimas grew up in Soviet Russia, and sought political asylum in 1988 at the Iranian Embassy in Moscow. Perhaps Rimas refuses to be bound by any convention, even the rules of seamanship.

"I tried to take his last boat from him," said Mondeau, who told a harbormaster, "Dude, I’ll give you a hundred bucks if you can stop him and call him manifestly unsafe." But once Rimas sets his mind to something, Mondeau said, there is simply no stopping him.

Big Boats in Seattle

The Puget Sound Sailing Championship for Small Boats was followed up, of course, by the PSSC Big Boats, held on Seattle’s Shilshole Bay. Photographer Jan Anderson describes the regatta: "No rain, an occasional shot of sun, all in all terrific weather for a regatta — oh, yeah, if only there was a bit more breeze! Current played a big role, as did patience, luck, good looks and an enduring smile-and-wave attitude."

The event, for 56 entries on two courses, was hosted by Corinthian Yacht Club of Seattle on October 14-15. The bigger Big Boats raced on the North Course, while the smaller Big Boats sailed on the South Course.

See results from the regatta here, and see more of Jan’s excellent photos here.

Man Overboard Practice to the Rescue

The man overboard. How that brought such dread while trying to pass the practical test before getting a sailing certification. I heard stories of people who passed all other components of the test, and then just couldn’t get Bob — the elusive orange juice container — out of the water. Oh please don’t let that happen to me.

It didn’t. I got Bob and passed the PT. Phew. And then my husband, David, had a great idea. I mean that sarcastically.

“Think about it,” he said. “Doing the man overboard procedure was the scariest part of the practical test. But imagine if — God forbid — we really have to do it. The stress would be much, much worse. So I think that every time we charter a boat, we should practice. A few times each, just to keep our skills up.” He had a point. A good one. It kills me when he’s so obviously right.

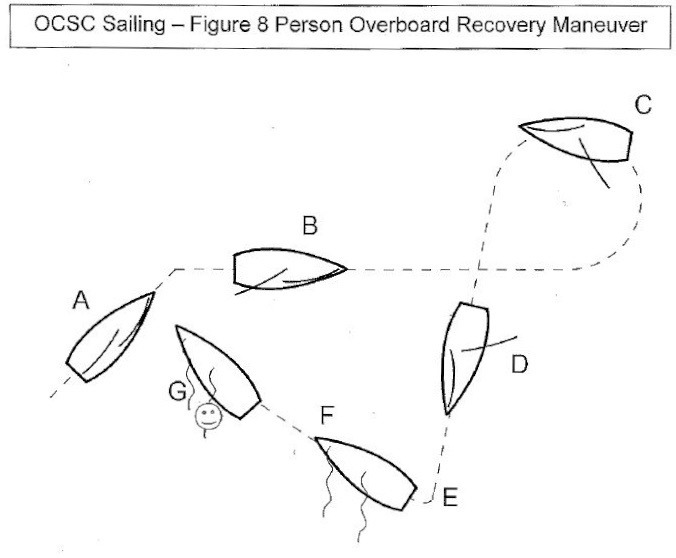

So we did. Every time we took out a boat from OCSC in Berkeley, we each practiced the man overboard procedure, often several times. It’s become part of our normal routine now: Leave the marina, raise the sails and throw Bob over. We explain the maneuver to our crew, especially the ones new to sailing, and use that to finish off the very thorough safety talk David gives ashore.

But one day, we actually needed it.

We were sailing with two of my friends, both of whom had never been in a sailboat before. David was at the helm, and I was alerting him to traffic when something small caught my eye. “Maybe it’s a kayak,” I said. “Or a downed kitesurfer.” Several other boats were passing it, so I assumed everything was okay — but we kept an eye on it.

But as we got closer, we realized it was an overturned, very small boat. A young man was sitting on the sideways hull, wearing shorts, a T-shirt and no life preserver. His female companion was in the water, holding onto the boat with one hand. We yelled out to see if they needed assistance. Despite several other boats having passed them by, they waved frantically. David and I turned to our two novice sailors: “Remember the maneuver we practiced this morning?”

“Oh yeah,” responded one of them. “So our job is to point at the people, right?” I sighed, relieved that they could contribute to the rescue instead of raising the stress level even more. I told my other friend to call 911 and ask for the Coast Guard.

There were scary moments, such as when the young woman began swimming toward our boat, which forced us to change tactics for the rescue. We struggled to get her onboard as the Coast Guard was approaching.

I wanted to get her a fleece jacket from below. “The Coast Guard is already approaching. They’ll have things to keep her warm,” said David. Moments later, the CG pulled alongside and took the rescued woman aboard their vessel. I asked if they wanted my fleece for her. “We’re the Coast Guard,” said one young man. “We have things to keep her warm.” Seriously, he used the exact same words David had just said to me. (He was right again, dammit.)

As soon we began sailing, I called OCSC to fill them in. It might not have been my clearest communication, as the adrenaline was kicking in: “I think we, uh, just rescued somebody. From a tiny boat flipped over in the water. And lots of other boats went past it! But we got her out of the water and the Coast Guard came for her and I thought they might be calling you.” All of that in about 15 seconds. The OCSC manager was very surprised and supportive.

Because the man overboard procedure was routine to David and me, we were able to remain calm and work together during a very stressful situation. And because our novice crew had already practiced it, they were able to participate in the rescue without the panic that could otherwise have very easily taken over.

At the end of the day, one of my friends exclaimed, “We’ve seen so many exciting things in the Bay today: sea lions, dolphins and people!”

The question isn’t do I want to practice the man overboard procedure, because that answer is “No!” It’s difficult, stressful, and scary to think of the real-life situation that would require that maneuver.

But that’s not the question we sailors should be considering: It’s not whether we want to practice the MOBs, it’s whether we should practice. And that answer is always a resounding: “Yes.”

Jacquelyn learned how to sail with her father, Guy Urbani, on Chesapeake Bay. She and her husband, David Malmud (both East Coasters), moved to San Francisco 12 years ago, specifically for the sailing opportunities. They still think it was a great decision.

Do you have a good MOB story, cautionary tale or advice? Let us know.