Why ‘Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World’ Is the Greatest Sailing Movie of All Time

After the Hollywood award season came to an end last week, a little hyperbole and pablum about cinema seemed in order: We’re calling Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World the greatest sailing movie of all time.

Nearly the entirety of Master and Commander (94% — I measured) takes place on a ship under sail. The movie is thoughtfully directed, well-acted and beautifully written — the amalgam of three Patrick O’Brian novels from the 20-book Aubrey–Maturin series. It’s a Hollywood blockbuster set on the high seas that has the gravitas of a historical, sweeping epic, combined with the edge-of-your-seat pace of a popcorn action flick. The film garnered critical acclaim and was a “moderate” box-office success. It’s full of drama, intrigue, surprise (forgive the pun), swashing and buckling.

Released in November 2003, Master and Commander was nominated for 10 Academy Awards, including best picture and best director for Peter Weir; the film won for cinematography and sound editing. And now, 21 years after its release, Latitude 38 is proud to declare Master and Commander the greatest sailing movie ever to grace the big screen.

Act One — 1805. North Coast of Brazil

In the glaring moonlight, we see a silhouette of the 28-gun, 197-soul English frigate HMS Surprise. Her mission: to intercept the French privateer Acheron, which threatens to tighten Napoleon’s grip on the world.

We’re onboard a ship under sail, our ears filled with creaking and groaning. (A sailor might hear the soothing drone of a night watch.) We see rows of hammocks swaying from the interior like cocoons. We pass livestock and rows of cannons — one is named “Sudden Death.” Two bells are struck, and the watch changes with sailors descending and ascending the rigging in the predawn moonlight. Not a word is spoken, nor barely a character seen, for the first two minutes of the movie.

A ghostly silhouette is spotted in the fog. (It’s the Acheron.) The crew beat to quarters, and we’re introduced to our dashing, ponytailed hero, Captain Jack Aubrey, played by Russell Crowe. Through his telescope, the captain sees a flash in the fog. “Get down!” Surprise is smashed and splintered with cannon fire, but the crew never fails to be extraordinarily English: “Damage report if you please!” We are instantly under the, calm, confident command of Captain Aubrey, who never fails to be debonair.

Surprise is crushed by fire again. Rigging and decks explode. Water gushes in and there’s blood all over the deck. Captain Aubrey is down, maybe wounded, and as a viewer on my 10th-plus rewatch, I genuinely wonder if our newly introduced heroes have been defeated in the first 10 minutes of the movie. Alas, with Aubrey’s guile and the crew’s muscle and bravery — which will play out again and again — Surprise is pulled to safety in the fog, soundly beaten.

After repairs, she intends to pursue the Acheron.

At its heart, Master and Commander is an immense chase scene, with interludes of microdramas between the crew set in a microcosm of 19th century British society, where class is strictly divided, even in extremely close quarters. (We never see a soul on the Acheron until the end of the film.) We get to know the crew and look forward to their company — many of them have only a few lines and mere minutes of screen time. There’s 13-year-old midshipman Blakeney, who’s injured in the first battle and has his arm amputated in a graphic scene. There’s the battle-scarred but always cheerful Lt. Pullings, the eagle-eyed coxswain Bonden, the grumbling, cantankerous cook, the wise older sailing master Mr. Allen, and the timid Mr. Hollom, who will be labeled a Jonah — a cursed, doomed man. We’re sweating, shivering, sloppy drunk and shoulder to shoulder with a crew in peril, bored, at war, and having a grand adventure.

Act Two — Confrontation

I’m sure there’ll be some “Which is better?” debate about Master and Commander the books vs. the movie. I haven’t read any Patrick O’Brian novels, and I’m sure they’ll be some grumblings as to my qualifications to critique the movie. But on this last rewatch, I became fascinated by the relationship between Jack Aubrey and ship’s doctor Stephen Maturin, played by Paul Bettany. Aubrey, a navy man, swashes and buckles, while Maturin, an educated deep thinker, wants to explore and do science. Maturin is skeptical of power and authority, while Aubrey is the power and authority. Aubrey plays the violin and Maturin the cello, and the two perform a kind of opposing duet throughout the film, both musically and dramatically, creating the moral tension that’s key to cinematic drama.

After being caught by the Acheron again, but masterfully deceiving her and eventually sneaking up behind her, Surprise is in hot pursuit all the way to Cape Horn. But Aubrey — driven by his damned hubris, as any flawed hero is — pushes too hard, snapping a mast he knew to be compromised and losing a man overboard. The pace of the movie and the chase slows to a crawl, which might remind sailors of the vacillations of life at sea. Much like a passage (and this article), the movie is long — with a running time of two hours and 18 minutes.

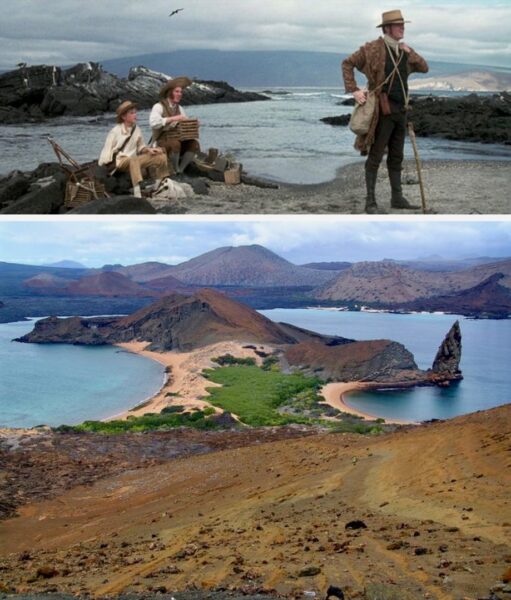

Aubrey offers Maturin a chance to explore the Galápagos Islands, but as they arrive at the archipelago, they learn that the Acheron has just departed. This leads to a perfunctory argument to display that elemental tension between the two main characters. “We don’t have time for your damned hobbies, sir,” Aubrey screams, almost making fun of his friend after enticing him with the promise of exploration.

“I must hurry past inestimable wonders [for a pursuit] bent solely on destruction. I say nothing of the corruption of power,” Maturin counters. These are the morally diametric points of view: war, peace and the pursuit of discovery. Everything must be sacrificed for the chase.

But in a wonderful twist, both Aubrey and Maturin will sacrifice their own dramatic needs for the other man’s desires.

Intermission — Behind the Scenes

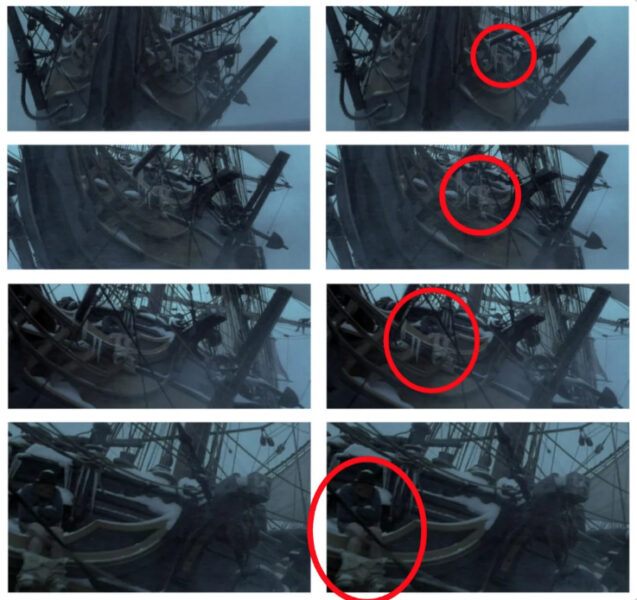

— The majority of the Master and Commander shoot took place on a full-scale replica, mounted on gimbals, at Baja Studios in Rosarito; it was the same 20-million-gallon tank originally built to film Titanic. There were a mere 10 days of filming aboard the real-life Surprise, a 1970-built replica of the 18th century Royal Navy frigate Rose, now bearing her movie name and berthed on the San Diego cityfront. There were also “miniatures” (one was up to 34-ft long) and lots special effects. Footage taken while aboard a replica of Captain James Cook’s Endeavour rounding Cape Horn in 2002 was digitally incorporated into Master and Commander’s Southern Ocean scenes.

— Surprise was chasing an American vessel in the Aubrey-Maturin novels, but in 2001/02, the studio had to consider the sensitivities of a post-9/11 audience … and the French were easy targets at the time.

— In 2000, Tom Perkins wrote of Patrick O’Brian in Latitude 38: “1) his capacity for serious drinking greatly exceeded my own; 2) his reserve only eased very slightly in the presence of this unknown American (me) and; 3) his knowledge of the practical aspects of sailing seemed, amazingly, almost nil.”

— Best quotes, all from Aubrey/Crowe:

- “Do you not know that in the service … one must always choose the lesser of two weevils?”

- On the captain of the Acheron: “What is it with this man? Did I kill a relative of his in battle perhaps? His boy, God forbid?”

- “Name a shrub after me — something prickly and hard to eradicate.”

— As Surprise sails in frigid weather (upon a digital sea), a crewman is briefly seen defecating on the bow.

— Russell Crowe was at the height of his superstardom, coming off three-straight years of acting nominations — including a win in 2001 for best actor in Gladiator — when he was cast for Master and Commander. There are moments, however, when I feel like he’s not quite pulling off his stately English accent. (Or that it feels forced.)

Crowe holds the space as captain well and is so obviously in command of men both younger and older than he is. (He reportedly arrived on set a week early so that he’d have an air of experience when the rest of the cast arrived.) You can’t not root for or be legitimately inspired by him, and I can’t imagine another actor in the role, but something about his performance, which is otherwise perfect, has always felt a little off.

Act Three — Resolution

Maturin is accidentally shot at sea, and the best chance to save him is to get back to shore. (Maturin actually performs surgery on himself, another uncomfortable scene taken from the books.) Even though the Acheron is finally in sight, Aubrey gives up the chase to save his friend.

We’re soon on land for the first and only time in the movie, with Maturin convalescing while the crew plays cricket and distills spirts from cacti. Once he’s well enough, Dr. Maturin sets out across the island to collect samples, all under the hypnotic score of Bach’s cello suite No. 1 in G major. All Galápagos scenes were shot on location, and it’s here that Master and Commander feels like something higher-brow than your ordinary Hollywood flick.

Reaching a high peak on the other side of the island, Maturin sees the Acheron. He knows that he must abandon everything, again, for war. Aubrey hatches an ingenious plan after seeing a phasmid, an insect that disguises itself as a stick, which Maturin collected — Surprise will disguise herself as a whaler to draw in the Acheron. “I had no idea that a study of nature could advance the art of naval warfare,” Aubrey says.

Preparations are made for the final, brilliant act, where the element of surprise (pun intended) wins the day. I won’t bother with a blow-by-blow of the final battle — rest assured that our heroes win the day, but not without tragic losses.

After the battle, Surprise is headed back to the Galápagos yet again. Aubrey was told by the Acheron’s doctor that their captain was killed in battle, but Maturin tells Aubrey that the doctor actually died months ago. Le capitaine is still alive? (You guys couldn’t have gotten together before the Acheron sailed and figured that out?)

And it’s here that Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World solidifies itself as an incredibly well-told story, and the greatest sailing movie of all time. Even though both Aubrey and Maturin traveled their moral arcs and sacrificed their own fundamental desires for the other man, they cannot escape the chase.

Wonderful Article. It would be a great movie to see at an outdoor screening one summer night.

Enjoyed the movie and have read all the books. Something the reviewer should do if they want a better perspective.

Thanks, anonymous commenter. I think it’s possible to critique the movie as a stand-along piece of art, rather than cross reference through a 20-book series.

As I said, this last rewatch has inspired me to dive into the Aubrey-Maturin series to explore the relationship between the two men.

My wife (Ann) & I read the first 19 of Patrick O’Brien’s 20 Jack Aubrey novels in the ‘90s prior to a fulfillment of our prenuptial agreement (her insistence) that we plan and execute a multi year sailing cruise after our retirement. We married in 1991. Her father had the same dream but died prematurely at age 48. I found the novels to be the best sea literature that I had ever read or have since read. I have been sailing for 59 years. I have made 19 ‘blue water’ passages each in excess of 2000 miles starting in 1966 on my 22 foot sloop ‘Isle of Skye’ from Acapulco to Hawaii in vessels ranging from 19 feet to 67 feet, racers and cruisers. O’Brien’s descriptions of the sea and sea states, sailing ships, and life at sea (as reflected in the marvelous film ‘Captain and Commander) are unequaled in literature & film that I have experienced. I’m a bit bewildered by this writer’s admission that he has never read O’Brien but can make a judgement on O’Brien’s knowledge from third party hearsay.

Hi Tom — Thanks for your comment.

I never made any judgement about Patrick O’Brian’s knowledge. I just think it’s an funny/interesting quote from someone who called him a “dear friend.” Most writers are tasked with writing about things that are beyond their realm of experience and expertise.

Galapagos island is near Ecuador, they are sailing to cape horn. How is it possible??? It’s on the other side of south America…