The New New England, Pt. 3

The leaves in New England were just starting to change as of about two weeks ago. Reds, yellows and oranges tinged the tips of Maine’s abundant trees, suggesting the profoundly beautiful, fleeting change that was to come, but that had yet to fully take its grip. In mid-September, the remnant of Hurricane Florence worked its way to the Northeast, dropping a few inches of rain in a few hours. There was no significant wind or swell associated with the deluge, it just rained and rained. I thought about all the cruisers at anchor: Surely their hatches would be tested for leaks on this day. (That morning on the news, there was a story — and this is true — about a restaurant in Maine giving lobsters marijuana before throwing them into boiling water.)

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

My family and I made the hour-and-a-half-ish trek from York to Bath to visit the Maine Maritime Museum, one of the few “intact” shipyards from the 1800s, and a place that exemplifies my theme for this series about how the old meets — or clashes awkwardly, even violently with — the new. On the road to Bath, there was forest as far as the eye could see, with the colors becoming a little more prominent as we went north. As a Californian, there’s something overwhelming about the sheer density of New England’s wooded-ness. Driving anywhere, you realize that every road and plot of land for buildings is cut forest. Every single inch of terra firma, right up to the beach, is trees, trees.

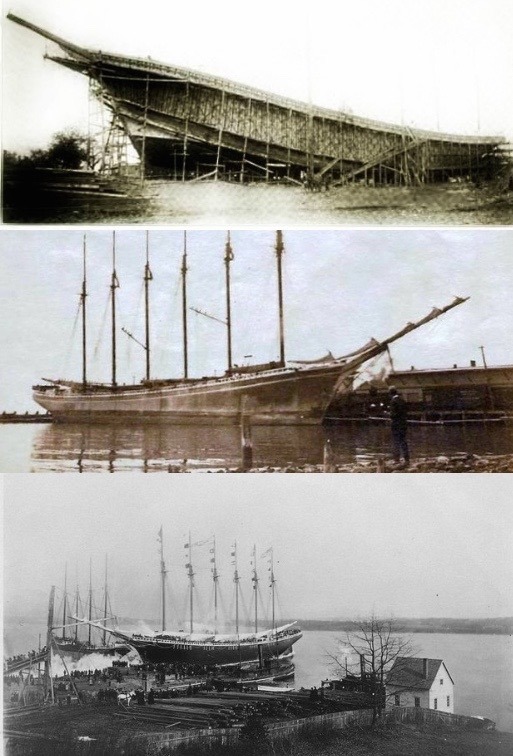

Plopped in the middle of Maine Maritime, also known as the former Percy & Small shipyard, is a skeletal structure of what you eventually realize is meant to represent a ship . . . a giant ship. It’s a to-scale representation of the Wyoming — at 450-ft long, the six masted schooner was the largest wooden ship, and largest commercial sailing vessel, ever built.

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

Constructed in 1909, the Wyoming was designed to carry coal (6,000 tons of it), loading up in northern Virginia or Pennsylvania, and sailing as far south as Argentina. The Wyoming ran aground and sank off Cape Cod in March 1924. All hands were lost.

I’m never sure what mindset to adopt while strolling through a museum: dutiful, respect? Stoic observation? The Wyoming was not that far in the past; she sank less than 100 years ago. Part of her history and lore seems ancient and distant, and yet it’s not that hard to imagine the people who built and sailed her. (“Our lives as brief as a butterfly’s cough,” Webb Chiles wrote.)

Just up the road from Maine Maritime is Bath Iron Works, a huge, active and well-staffed shipyard that primarily builds destroyers for the US Navy. Founded in 1884, BIW has been a subsidiary of General Dynamics since 1995. According to the Wikipedia history of the yard, “During World War II, ships built at BIW were considered by sailors and Navy officials to be of superior toughness, giving rise to the phrase ‘Bath-built is best-built.'”

© Latitude 38 Media, LLC

Strolling through the interior of Maine Maritime, I came across a few models of “pinky schooners.” It took a moment for that name to reverberate, until remembering where I’d heard it before. During a visit to Berkeley Marine Center last May, I saw the pinky schooner Tiger on the hard, and had a quick chat with her owner, Luc McSweeney.

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

“These boats were workhorses 100 years ago on the East Coast,” McSweeney, a merchant marine and charter boat captain told me. Standing in front of the models in Maine, I felt the past-and-future merging thing again, but couldn’t ascribe the significance I wanted to. Things just . . . moved on. We can fuss over history, interpretation, and aggrandizing as much as we want, but time doesn’t care. Time just keeps on ticking, ticking . . . ticking (or slipping) into the future . . . according to the Steve Miller Band.

The last place we stopped was the “woodshed,” where a group of kids were gathered and presumably working on a project. A dinghy sat in one corner, its frames recently finished and waiting for planking. One of the volunteers told us that Maine Maritime receives one group of students every single week, year-round — an impressive feat for any museum, and a sure sign that the past has a future.

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

“I wish there was something like this when I was a kid,” I told one of the volunteers.

“So do I,” he answered.