Kris Larsen and the ‘Kehaar Darwin’

Last Wednesday in ‘Lectronic Latitude, we reported on a "Strange Boat Rescued off Maui." One reader commented: "Every man and woman who owns a boat, loves their boat above others. It’s just not good manners to disrespect another person’s boat." Curious and inspired, we looked for more information on the homemade, engineless junk-rigged vessel Kehaar Darwin and her skipper Kris Larsen, an interesting character with lots of ocean miles. (Technically the vessel is just called the Kehaar . . . Darwin is the boat’s port of call, and has mistakenly been added to the name.)

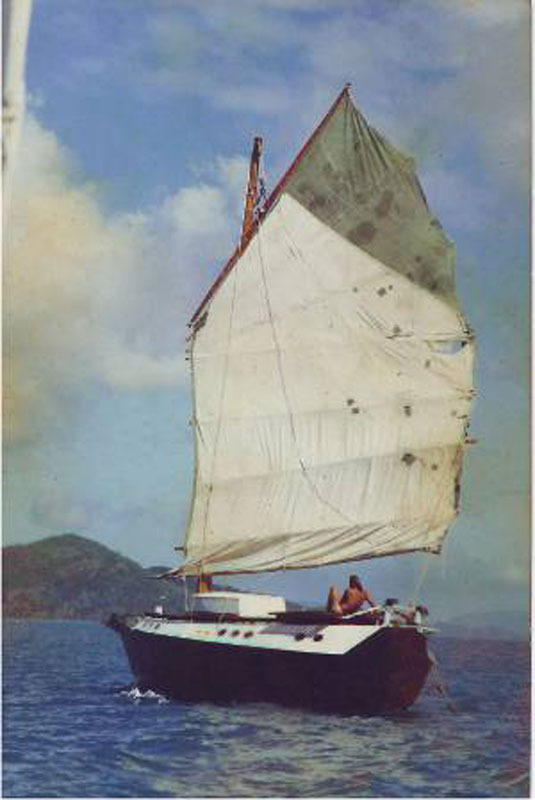

Larsen is the author of Monsoon Dervish, a book that documents many of his travels at sea, as well the ethos behind his lifestyle. It’s also the title of his website, which includes excerpts from his writings. Larsen is described as a middle-aged carpenter and navigator who has "criss-crossed the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific for seven years, from Australia to Madagascar and Japan, covering a total of 45,000 miles." The Kehaar is described as a 31-ft Chinese junk with no engine, electricity, radio, GPS or compass.

On the Junk Rig Association web page, several junk devotees took issue with the USCG calling the tow a ‘rescue’. "We were once visited by the Spanish authorities, because we were acting suspiciously," wrote one member. "It was nearly calm and we had been making minimal progress for about three days. Sailing instead of motoring is apparently suspicious activity." Another member said that, "Contrary to reports, the [Kehaar’s] sail was not in poor shape. It may be a classic case of people not understanding junk rigs. They can look untidy when furled or reefed." We recall more than one occasion when our sails looked like a college dorm room.

And Natalie Uhing, Kris Larsen’s partner, was quoted in the Sydney Morning Herald as saying, "This is very ordinary in the sailing world. I don’t understand what the fuss is about. Much ado about nothing, trust me. He asked for a tow, the guy called the Coast Guard. A boat without an engine or technology seems to be the cause of all the excitement."

Larsen was featured in a 1999 Cruising World article by James Baldwin. Born in Czechoslovakia, Larsen "had gone from picking fruit in Europe to sandblasting ships in Singapore to digging for gold in New Zealand." He married, and worked on building houses and shearing sheep in Tasmania before experiencing a "few bad breaks, which [Larsen] now blames on a weakness for Aussie beer." He would end up divorced and homeless before quitting booze and preparing for his dream of sailing. (Baldwin’s article has been expanded into an excerpt from his book, The Next Distant Sea.)

After purchasing the unfinished steel hull that would become the Kehaar, Larsen, like many self-sufficient adventurers, used recycled materials to outfit her, including "hardwoods from junked picnic tables and church pews." Larsen left Tasmania, cruised the Great Barrier Reef, and eventually ended up in Darwin, Australia, "with the vague notion of continuing on to Africa." In Darwin, he joined a yacht club, "the members of which were mainly like-minded outcasts from mainstream society." Larsen was quoted as saying that, "If you didn’t have a cupboard full of skeletons, you wouldn’t turn up in Darwin in the first place." Larsen would eventually sail to Mauritius, then on to Madagascar and Durban, South Africa, where government officials reportedly considered holding the Kehaar until he had "proper registration, an engine, a VHF radio and a life raft."

Which brings us back to Larsen’s arrival in Maui last week. With sailors such as Rimas Meleshyus or the curious case of the Sea Nymph, many in ‘The Land of the Free’ have a hard time letting people pursue their own path, though much of that concern seems to come from issues of taxpayer expense, rather than a respect for individuals and ‘free choice’.

Larsen’s 45,000 miles demonstrate why none of us should judge a book by its cover. Glenn Tieman is another case in point. Known as one of the world’s thriftiest cruisers, Tieman has sailed thousands of miles in his homebuilt 38-ft cat Manu Rere, and uses kerosene lamps on his boat, while Larsen uses candles on his.

"Fortunately, [the] media scrum has had no impact on Kris, whatsoever," wrote Natalie Uhing on her blog (Uhing has sailed with Larsen before, and works as an artist in Darwin). "What others say he can or can’t do isn’t [Kris’] problem. In fact, he quite enjoys playing the ‘gormless idiot’ in the presence of scandalized, angry ‘proper sailors’. It makes them feel good about themselves, they pronounce him a lost cause, and swagger off with a ripping good story to tell The Boys back at the yacht club, leaving him alone to get on with his plans."

But Uhing reminded us that Larsen is not an "arrogant and unlikeable maverick. A maverick he is, for sure, but not actually one that you’d take a personal dislike to. He doesn’t brag about what he does, is unassuming and grateful, and he is always respectful (especially when confronted by critics, preferring to hold his peace and cultivate the other person’s tolerance, than to beat his chest and defend his sailing practice)."

Larsen, Tieman and many others challenge what is considered the sailing norm. While some people are fussing ashore, they’re off enjoying life as they like it.

We’re curious to hear what you think.

This article has been updated.

He’s lost again. See Boatwatch: https://boatwatch.org/news/bolo-for-sv-kehaar-darwin-australia-to-mexico/

“Experienced sailor?” No communications equipment on board. Take a lesson, Pilgrims.