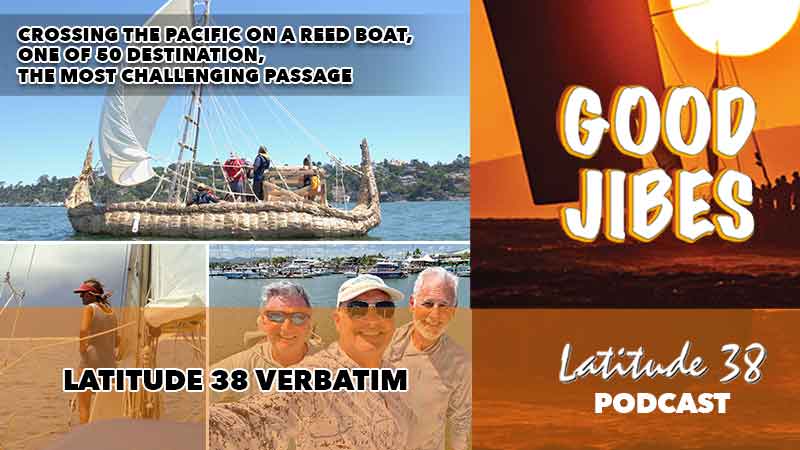

Episode #231: Reed Boat, 50 Destinations, and A Challenging Passage (L38 Verbatim), with Host Monica Grant

Welcome to Good Jibes where you can experience the world of sailing through the eyes of the West Coast Sailor. Featuring stories and tips from West Coast sailors on topics from our sailing community about cruising, racing, adventure, exploration or just plain sailing.

This week’s host, Monica Grant, reads three articles from the February 2026 issue of Latitude 38. Hear “Crossing the Pacific on a Reed Boat” by Monica Grant, “One of 50 Destinations in Seas Less Traveled” by Nick Coghlan, and “The Most Challenging Passage” by Jim Yares.

Here’s a small sample of what you will hear in this episode:

- What is Expedition Amana?

- Where is Twitchell Island?

- What’s Pampatar like?

- When was Alexander von Humboldt in Venezuela?

- How do you use MetBob?

Follow along and read the articles:

“Crossing the Pacific on a Reed Boat”

“One of 50 Destinations in Seas Less Traveled”

“The Most Challenging Passage”

Listen to the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and your other favorite podcast spots — follow and leave a 5-star review if you’re feeling the Good Jibes!

Check out the episode and show notes below for much more detail.

Show Notes

- Reed Boat, 50 Destinations, and Challenging Passage (Latitude 38 Verbatim), with Host Monica Grant

- [0:16] Welcome to Good Jibes with Latitude 38

- “Crossing the Pacific on a Reed Boat” by Monica Grant

- [1:02] Follow along and read the article at https://www.latitude38.com/issues/february-2026/#36

- [1:15] Expedition Amana

- [3:25] Jin Ishikawa

- [5:14] Twitchell Island

- [6:38] Learn more at Expedition-Amana.com

- [6:45] Find a boat. Find crew at the Latitude 38 Crew List

- “One of 50 Destinations in Seas Less Traveled” by Nick Coghlan

- [7:28] Follow along and read the article at https://www.latitude38.com/issues/february-2026/#50

- [8:55] St. George’s, Grenada

- [10:57] Pampatar

- [13:40] La Tortuga

- [16:05] Alexander von Humboldt

- [17:17] Check out the Latitude 38 First Timer’s Guide

- “The Most Challenging Passage” by Jim Yares

- [18:04] Follow along and read the article at https://www.latitude38.com/issues/february-2026/#73

- [19:28] Passage Guardian

- [20:35] MetBob

- [25:05] Opua

- [25:48] Cook Islands

- [26:42] Tauranga Marina Boatyard

- [27:25] Learn more at SailRoam.com

- Check out the February 2026 issue of Latitude 38 Sailing Magazine

- Make sure to follow Good Jibes with Latitude 38 on your favorite podcast spot and leave us a 5-star review on Apple Podcasts

- Theme Song: Pineapple Dream by SOLXIS

Transcript:

Please note: this transcript is not 100% accurate.

00:03

Fiji to New Zealand was the most challenging ocean passage I’ve ever done.

00:14

Welcome to the Good Jibes podcast brought to you by Latitude 38, the magazine for West Coast sailors since 1977. We invite you to experience the world of sailing through the eyes of the West Coast sailor. Featuring stories and tips from West Coast sailors on topics from our sailing community about cruising, racing, adventure, exploration, or just plain sailing. So sit back, cast off, laugh and learn and have more fun sailing. Today, we’re going to bring you three stories

00:43

from the February issue of Latitude 38. We’re sharing crossing the Pacific on a reed boat. We take you to one of 50 destinations in seas less traveled. Finally, the most challenging passage.

01:01

crossing the Pacific on a reed boat by Monica Grant from Latitude 38. A hypothesis suggests that before Polynesians arrived, Native Americans may have crossed from California to Hawaii in reed boats. Explorer Jin Ishikawa is heading a years-long project, Expedition Amana, to test that theory by constructing a reed boat that will sail almost 2,500 miles across the Pacific from San Francisco Bay

01:30

to the Hawaiian islands over the course of two months. The aim of the project is multifaceted. A scientific experiment in ancient navigation techniques, a cultural study of reed boat traditions, and an exploration into how humans relate to nature in the age of technology, all presented in the form of a live educational voyage for audiences around the world. Our is to both verify what was possible thousands of years ago

01:59

and to reconnect people today with the natural intelligence that guided early seafarers,” says 58-year-old Jim. Expanding on this premise, Jim explains that the ancient navigators may have reached the Hawaiian archipelago, or at least traveled partway, using knowledge of wind, swell, and stars. Expedition Amana is conducting real-world tests of that possibility. Reed boats were technologically capable of long-distance travel far earlier

02:29

than commonly believed, Jin says, adding that reed boats are among the oldest watercraft known to humanity. Reed boats are highly buoyant, flexible in large ocean swells, and are made of a simple lightweight construction with no metals, screws, nails, or bolts. It is, Jin says, the most primitive kind of boat made of reed stalks packed into bundles. In 2023,

02:56

Expedition Amana launched a 30-foot prototype, a reed boat that had been built in Sausalito. The plan was to test the boat’s seaworthiness in preparation for a larger model to cross the Pacific. While a reed boat might sound a little flimsy, the lightweight reeds are filled with thousands of tiny air pockets that give it flexibility, and most important for the project, buoyancy. Gina Shikawa is not the first person to embark upon building reed boats.

03:26

There have been many, some more successful than others. A descendant of the Ohlone Tribe, a Native American tribe of the Greater Bay Area, Linda Yemani has spent many years resurrecting the technologies and skills of her people using the chille reeds from the region. An article published by Santa Clara Magazine in November 2019 describes Yemani’s efforts to build a traditional reed boat.

03:54

Along with learning how to harvest, store, and dry the reeds, she had to overcome simple problems such as mold, mildew, and water incursion, challenges that Gin also faces.

04:08

Jin has invested ample time and energy learning the intricacies of the boats and the materials. He has sailed more than 8,000 miles aboard ancient-styled vessels, hosted numerous reed boat building workshops, and has built some 300 reed boats. In 1999, Jin joined a Spanish explorer attempting to sail a 95-foot reed boat from Chile to Japan. The vessel became infected with mollusks and was half-eaten.

04:37

he told CNN at the time. The boat began to unravel and was carried on the wind and currents to a small group of South Pacific islands. We perfectly drifted there without control, Jin told the San Francisco Chronicle in May, 2023. In that time, I felt that the Reed boat is a living thing. That inspired me.

04:59

Expedition Amana harvests its tulle reeds from Twitchell Island in the California Delta, where the organization is working with the California Department of Water Resources to learn more about the reeds and their role in the natural habitat. After 12 voyages over three months of testing, the 30-foot Amana was returned to the wetlands where its reeds had been harvested, in keeping with ancient sustainability practices.

05:26

The boat will break down and become fertilizer for newly sprouting reeds, which in turn will become future trans-Pacific boats. In his own way, Jin is creating what he calls an organic form of AI, ancient intelligence. From an archaeological perspective, reed boats were technologically capable of long distance travel far earlier than commonly believed.

05:51

We believe that reconnecting with natural navigation is not a spiritual exercise, says. It is a form of human knowledge that our species has nearly forgotten. By sailing in this way, we hope to bring that ancient intelligence back into modern conversation. The project is currently seeking financial support and active volunteers. Amana was built with help from around 100 people. The new Amana

06:18

will require about 5,000 bundles of churries, with harvesting, construction and backend administration demanding many hours and many hands. If you would like to help or learn more, visit www.expedition-amana.com. Thank you. Hey, good Jives listeners. Are you looking to sail more? It’s the biggest mismatch on the California coast.

06:47

There are thousands of boats not sailing because they need crew and thousands more sailors or soon to be sailors who want to sail but can’t find a boat. For over 45 years Latitude 38 has been connecting boat owners with sailors to sail or race the bay or travel far over the horizon. Some connections have turned into thousands of blue water cruising miles or race winning cruise or long term relationships or just happy days of sailing.

07:12

If you have a boat or want a crew, add your name to the Latitude 38 crew list at latitude38.com. You don’t know where such a simple act will take you. One of 50 destinations in seas less traveled by Nick Coughlin. While Venezuela is in the news for its political issues, Nick Coughlin reflects on his and his wife Jenny’s Venezuelan cruising experiences in 1988 aboard their Alban Vega 27.

07:41

Taka, the otter. June too soon, July standby, August a must, September you’ll remember, October all over. This is a rhyme that everyone in the Caribbean knows to remind themselves of the approach of the hurricane season. Climate change means it’s not as reliable a guide as it once was. But for many years, June has seen cruisers seeking a mooring in one of the Caribbean’s few hurricane holes.

08:10

or heading south below 10 degrees.

08:15

In happier times, Venezuela was the default destination. Wonderful empty beaches on the offshore islands, a mainland coastline deeply indented with jungly coves and toucans in the trees, and friendly people. And, if yours was a powerboat, fuel cheaper than bottled water. People who tell you that the trade winds blow constantly and predictably in the Eastern Caribbean, and that it’s always sunny, are wrong.

08:44

We spent days hanging around in the crowded anchorage at St. George’s Grenada, waiting for the passage of a tropical wave, a trough that brings heavy clouds, thunderstorms, squalls, and shift in the wind from east to southeast before we decided it was the right time to make our move to Venezuelan waters. It was just two days before that July standby warning was due to kick in. Los Testigos.

09:10

A small group of near deserted islands 90 miles to the southwest was our first stop. They could not have been a greater contrast to buzzing Grenada. There were eight or 10 cruising boats scattered among three anchorages, each of which had its own sandy beach and colorful snorkeling among the fringing rocks. We spent the days swimming or walking in the dry scrub covered hills on the biggest island. A few cacti, perhaps refreshed

09:40

by the tropical wave were flowering. From the 250 meter summit, we could see all the way to Margarita Island, 40 miles to the west and to the mainland of South America. There was a small village that consisted of a few makeshift fisherman’s shacks and a more substantial pair of buildings that housed a three person Navy detachment. The young Tiente was wearing shorts and a t-shirt with holes. He barely glanced at our papers.

10:09

and wished us a happy stay in Venezuela. We should check in more formally at Margarita, he said. Life for the fishermen looked to be hard. There was no naturally occurring water on the islands, no electricity. Lacking ice, they would dry their catch in the open, which made for a stench around the settlement and great clouds of flies. When a second tropical wave came through, everyone rushed to bring in the fish and instead,

10:38

put out big blue plastic drums wherever drips accumulated. We took advantage of it to let our dinghy accumulate 2 centimeters, that is 0.78 inches of water, and used it as a bathtub.

10:54

The most popular anchorage on Isla Margarita was in those days a Venezuelan tourist trap and one of those not especially attractive places to which cruising boats gravitated in large numbers and became inexplicably rooted.

11:11

One enterprising husband and wife crew who spoke Spanish had taken advantage of this phenomenon and offered a service called Shorebase. They would take your paperwork around the necessary stops, customs, immigration and so on for a fee of 350 bolobars.

11:32

We very much prefer to do such things ourselves. Those fees, by the way, actually involved around 30 Bollabars. This is all part of cruising life. And while some officials can be difficult, we usually find that with a few polite words and a little flattery about their country, we make new friends. But Pampatar, we had to admit, had its uses. We had been experiencing problems for months with our alternator.

12:01

The electro-auto-carib saved us. Chief mechanic Antonio confirmed my diagnosis that the regulator was at fault. No, he didn’t have another in stock, he said. But then after some thought, he said, a fiat will do. He asked us to wait, went out of the front door of his workshop and looked up and down the street. We watched him walk away and around the corner.

12:29

He was back 20 minutes later with a used regulator, wires and all.

12:36

We were sure Antonio had simply lifted it from an unsuspecting car owner, but it worked. We sailed out to the islands again, this time to La Banquilla. There is a picture perfect cove on the western side of this island, described by cruising doyen Don Street as the most beautiful beach in the Caribbean that is known as the Bahia del Americano. The gringo in question was long gone. The house he had built in ruins.

13:06

the airstrip to which he once flew his millionaire friends overgrown and unusable. We had the place to ourselves. One night we made a fire with driftwood gathered from the beach, baking two large potatoes in foil on the embers, accompanied by a can of beans. As the fire died, we watched the stars setting over the empty ocean to the west. La Tortuga reached after another night sail, this time to the southwest. We anchored first at Playa Caldera.

13:36

Two fishermen and a young boy came out to see us. They presented us with a meadow, a grouper, and Jenny went below to find what we could offer in return. Counterintuitively, it was two small tins featuring Charlie the tuna, which had been with us for at least two years, that lit their eyes up. As they prepared to head back, one of the men hesitated, then said, Oiga, listen, if you see anything or hear anything in the night,

14:06

Don’t worry, but don’t come out. Me entende? Understand? Later that day, we came across the wreckage of two light planes on a makeshift landing strip behind the shacks on shore. No, those planes were not the result of poor flying by Caracas Playboys, we learned. La Tortuga was a transit point for drugs bound for Florida. The wrecks represented a couple of shipments gone wrong.

14:33

The noises we should ignore would be from planet-stunned night landings and or high-speed launches. We moved to a location the fishermen recommended where no one would molest us. Keo Heradura Horseshoe Key, a low flat island off the northwest corner of the big island. When I think back years later and after 70,000 miles at sea,

15:01

It seems to me that of the hundreds of places we have dropped our anchor, this one was especially memorable. You see our chain as it snaked away on the white sand bottom. There were kilometers of shimmering, pristine beaches, pelicans at the shore, manta rays and angelfish in the shallows. As we snorkeled, we could hear the parrotfish munching on coral. We brought on board a few of the more interesting, uninhabited shells we found.

15:31

along with the jaws of a shark that must have fallen victim to the fishermen a year or two earlier. There was even an interesting, if enigmatic, morsel of history, something I always appreciated. Wedged among coral rocks and old conch shells behind the beach was a cracked plaque that told us that German polymath and explorer Alexander von Humboldt was at Keoharajur in July 1799.

16:00

There were signs even in 1988 that paradise was threatened. The two wrecked aircraft, the fisherman’s warning. And since our season off the coast of Venezuela, the country’s economy has collapsed. Amid political chaos, millions of people have become refugees in neighboring countries. Poverty has taken hold. Narco traffickers rule and violent crime has rocketed. Every Western government exhorts its nationals to stay away.

16:31

I take consolation in the fact that the reputation of Columbia in those days was equally or more frightening. Columbia has pulled through and it is safer now than it has been for many years. Cartagena has become a must on the cruising circuit. Venezuela will pull through too. The upper jaw of the shark is on the wall above our dining table at our home on Sol Spring Island in British Columbia. As I sit writing this, the shells are on the windowsills.

17:02

They remind me every day of distant anchorages under starry skies. Latitude 38 here. Are you thinking of sailing to Mexico or all the way across the Pacific or maybe even further? We just heard from Joanna and Cliff saying, my husband and I subscribe to Latitude 38 and enjoy the Good Jibes podcast regularly. They went on to say they’re headed to Mexico in the fall and will continue across the Pacific to Australia. However, they’re looking to simplify all the choices

17:31

they need to make to prepare. Of course, there’s tons of resources out there, but Latitude 38 does have a page on our website called Heading South. And we also have Latitude 38’s First Timers Guide to Mexico available to read online on the Heading South page or a printed copy that is available to purchase in our online store. There’s a lot to know, but Latitude38.com is a good place to start. The most challenging passage by Jim Yaris.

18:01

aboard the Katana 472 catamaran Rome.

18:08

Fiji to New Zealand was the most challenging ocean passage I’ve ever done. Not the longest, not the worst weather, not the most boat problems. It was timing the weather window and the variety of conditions that come with crossing three separate climate zones. Except for an unexpected batch of embedded thunderstorms in the middle of the trip, the weather was exactly what we, our routing software, and our expert weather pros had predicted.

18:37

Our routing software predicted the crossing would take five and a half to six days for the 1,100 mile trip. It took five days and 16 hours. Amazingly accurate given the complexity of the weather systems we crossed. It was a fast beam reach nearly the entire way. We were sailing along nicely in 10 knots of breeze when I got a WhatsApp message from Passage Guardian’s Peter Mott. Hi Jim, what wind do you have there?

19:08

He went on to alert us that boats ahead of us were running into squalls with strong winds. Peter Mott runs Passage Guardian, a free service that tracks boats on passages and coordinates their rescue if needed. We use his service in lieu of a traditional float plan filled with friends or family ashore. He messaged us one night to give us a heads up on the adverse weather ahead. We’d left Fiji with a few large, fast cats.

19:36

They would make New Zealand a day ahead of us, which meant that they would be running out in front. They served as our forward weather scouts, relaying their conditions back to us as we all sailed south.

19:50

Captain Glenn aboard the KC-62 Kinetic was feeding me weather conditions 60 miles ahead in the middle of the night. It was a big help. The gunboat 66 Slim was also out there with us. This kind of communication used to take place over marine single sideband radio. Today, it’s WhatsApp messages over Starlink. The squalls were short-lived, might’ve been six hours or so. When they passed,

20:19

we were back to sailing fast on a beam reach. As we often do on these passages, we enlisted the help of two professional weather routers. Met Bob, who has been routing us for the last two years, and John Martin of Ocean Tactics. He’s a popular choice among the cruisers here, and we subscribed to him for this trip as well. We rely on their input when evaluating the weather window and our target departure day. Once en route, we send them our position once a day.

20:49

and they reply with anything they see in the forecast that I might have missed. Sometimes they’ll advise a course change to take advantage of favorable current or winds. It’s a worthy team effort. This was our first passage using the new AI-based weather models. I was impressed with their accuracy. They are probabilistic in nature as opposed to the deterministic numerical models we’ve been using. Combined, they give you a good sense of what to expect and how to prepare.

21:20

This was the first passage without my wife, Pam. She went home to look after her family and her vacant house. Sailing together these past three years has brought us close. We gravitate to our strengths. Pam looking after the welfare of the crew, me looking after the welfare of the boat. On a passage we catnap during the day. At night we each stand rotating three hour watches. We make a good team. Which is not to say I didn’t have a great crew aboard for this trip.

21:50

I did. Richard and Dave were ideal. They put their lives on hold to come to Fiji and make this happen. Richard stepped into the role of shipkeeping and the care of feeding at the crew. He made sure we ate. Dave and I focused on navigating and running the boat. We all stood four hour watches. Those are long watches, but they give each person a full eight hours off watch. Sleep is a secret weapon on the ocean.

22:19

Richard is an ocean sailing veteran. He has a lot of miles in the Atlantic and Caribbean. We did a few passages together back when I lived on the Gulf Coast. Dave is relatively new to ocean sailing, having done a Baja bash from Cabo San Lucas to San Diego. He’s a consummate outdoorsman and a true MacGyver, the guy you want on your side during the zombie apocalypse. He adapted immediately to ocean sailing.

22:48

We made landfall at Apua on the north end of New Zealand’s North Island. My general strategy is to get off the ocean as fast as possible on long trips. Being the closest port of entry to Fiji, Apua fit that bill perfectly. Apua and the Bay of Islands marina are well equipped for the surge of transient yachts visiting New Zealand this time of year. We arrived in the middle of the night and slowly motor through the dense fog up the river.

23:17

Yes, it’s prudent to stand off and wait for daylight when arriving at an unfamiliar harbor. But I’d been here before, and the harbor is well-charted, well-marked, and well-lit. That said, the unexpected fog made us extra cautious. We slowly picked our way using the radar image overlaid on the electronic chart. By 4 a.m., we were tied up to the Q-Doc. As we were tying up,

23:44

I went to step off onto the dock and promptly fell into the water. The combination of fatigue, adrenaline withdrawal and land sickness struck again. It was a cold shock. Soon enough, we all had hot showers and naps and then began the day long process of getting cleared into the country. Customs, immigration and biosecurity were all very friendly. An interesting aspect of New Zealand’s biosecurity requirements

24:14

is that visiting yachts must have a clean bottom free of invasive species. We always scrub our hulls before leaving a country. But the Kiwis want photographic and video evidence of your clean bottom in advance of your departure from, in our case, Fiji. Our video was rejected as inconclusive. They couldn’t see the hulls well enough.

24:40

When the biosecurity lady came aboard in New Zealand, she and I sat at my laptop and reviewed the video. She was satisfied that we were clean and after inspecting the anchor chain and seizing most of our food, signed us off. We were officially cleared into the country.

24:59

We spent a day in Oppoa catching up with friends, cleaning the boat, doing laundry and fixing a few things that had broken. The weather looked good enough that we decided to head down the coast to Auckland. I’d always wanted to tie up my own boat in downtown Auckland’s famous viaduct harbour. Now I finally had the chance. We enjoyed a beautiful day in the city of sails after another foggy arrival. At this point, Richard and Dave booked their flights home.

25:26

After an amazing dinner at Chef Al Brown’s Depot Eatery, they were off and I was again solo. I still needed to get Rome another 100 miles farther south to Turinga, where we planned to haul out and leave the boat for a while. Fortunately, I was able to recruit our friend Michaela, whom we’d met in the Cook Islands. She was able to take a day off from teaching and help me make the overnight sail. My quick trip down the coast was a sampler of what cruising is like here.

25:54

And now I know why Kiwi sailors love it so much. There are countless anchorages and towns to enjoy. I’m looking forward to our return when we can slow down, head north, and enjoy all of the anchorages we blew past. We’ve reached the end of the Coconut Milk Run, the route following the trade winds from North America through the South Pacific Islands of French Polynesia, the Cook Islands, Niue, Tonga, Fiji, and on to New Zealand.

26:22

a long held goal, two years and more than 10,000 miles in the making. The boat is currently out of the water and in the capable hands of Tarangum Marina Boatyard, where talented boat builders and craftsmen are refitting and remodeling her. We’re back in the US for a few months to spend time with families over the holidays and we’ll tend to our slowly deteriorating house, which needs some love. As always, our plans are loose.

26:52

We expect to be back in New Zealand in February to inspect all the work being done and put the boat back into the water. Then we’ll enjoy some time sailing around this beautiful country. Maybe even join friends on the South Island Rally. The cyclone season in the South Pacific ends May 1st. After that, we may head back up to Fiji for another season there. Beyond that, who knows? Maybe Vanuatu? New Caledonia? Australia? Maybe back to New Zealand?

27:21

Plans are written in the sand at low tide. We hope you enjoyed our stories from the February issue of Latitude 38 and we look forward to seeing you next week for another issue of Good Jibes. Have a great week and sail well!