How to Watch SailGP

If you’d like to compare 5 knots to 50 knots, this is the weekend to take your boat out on the Bay. But keep your distance. SailGP is sailing on the Cityfront with practice races today and the two-day regatta tomorrow and Sunday. Some of the Latitude 38 crew will be off on the Vallejo Race; others will check out the action on the Cityfront.

Spectating from Shore

The SailGP Race Village will run along the Marina Yacht Club Peninsula between the St. Francis and Golden Gate Yacht Clubs. The village is open from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. It’s free to the public. Enhanced viewing experiences are available from the grandstand and official spectator boats. Fans on the grandstand and spectator boats will benefit from announcing and large-screen viewing, which, from our AC34 experience, really helps you follow the action on the water. To check on availability for tickets click here.

To follow more closely with your own tools you can download the app from iTunes or Google, listen in on VHF Channel 20, and follow along on Facebook Live.

Spectating from the Water

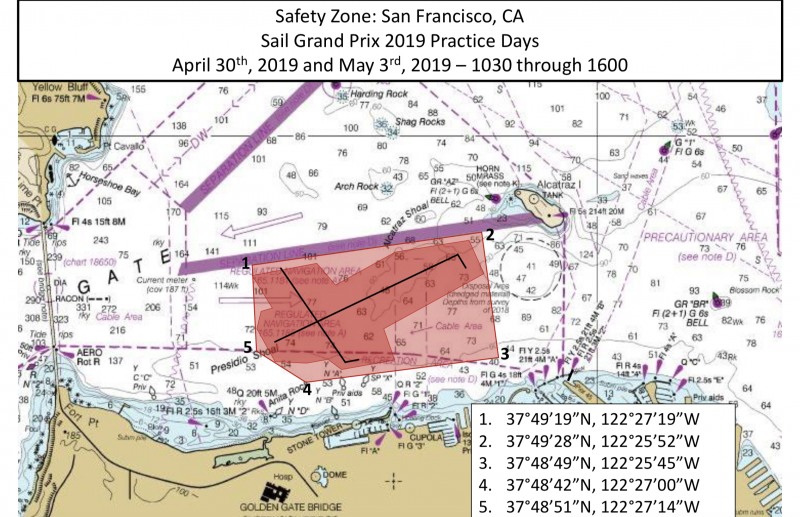

Following on the water allows you to see some of the action while taking in a good day of sailing. However, given the speed of boats and potential traffic, there will be strict Coast Guard exclusion zones. Today the exclusion zone will be in effect from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m., with practice racing from 12:30 p.m. to 2 p.m. The exclusion zone will be marked by a series of orange inflatable tetrahedron-shaped SailGP stake marks. Electronic markers identify the racecourse boundaries, and official SailGP boats will visually mark the racecourse perimeter. The north and south sides of the course are no-loitering areas, and spectator boats are encouraged to remain in one position.

Weekend racing will run from approximately 12:30 to 2 p.m., though, as we found on Tuesday when a whale passed through the racecourse, there can be delays. The race choreography is good, and the boats are fun to watch between races while they practice. Bring warm clothes and watch the sailors balance speed, tactics and survival on San Francisco Bay. To learn more visit SailGP-San-Francisco.

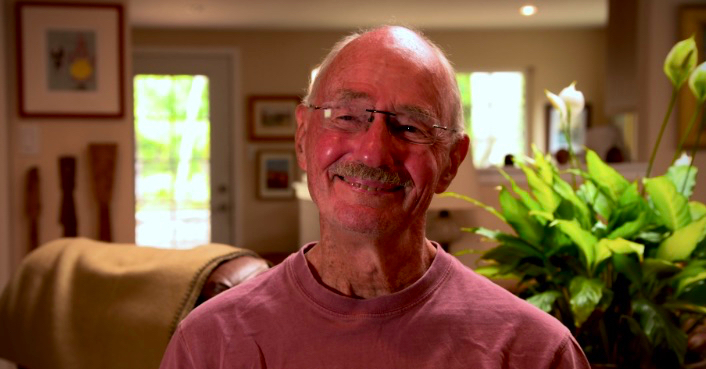

A Word from the Webb

Latitude Nation — On Monday, Webb Chiles completed his sixth circumnavigation of the planet upon his early-morning arrival in San Diego. The maestro himself wrote us a few days later:

At dawn on Monday, April 29, Gannet, my ultralight Moore 24, and I ghosted past Point Loma and entered San Diego Bay completing my sixth circumnavigation and her first and one of the most difficult and frustrating passages of the entire voyage.

I started my first circumnavigation in San Diego in 1974 and I am pleased with the symmetry of completing my last here 44 years later.

The voyage took almost five years, but could have been done in three. I spent an extra year in New Zealand because of a severed left shoulder rotator cuff and because I like New Zealand, and I spent last year on the East Coast after my wife and I bought a condo on South Carolina’s Hilton Head Island.

The final passage from Balboa, Panama, to San Diego was brutal without any severe weather. It was more prison of the sea than monastery. We never had more than 25 knots of wind and perhaps not more than 20. We had little rain.

I knew that there would be light wind for the first part of the passage and that we would be beating to windward for the last 800 or 1000 miles, but the windless hole for most of the first 1500 miles was beyond my experience or even imagination, and we were hard on the wind for probably the last 1500 miles, not 800.

Five of the six weeks of the passage were five of the six slowest weeks of the entire circumnavigation. One day we had a noon to noon run of 16 miles, and I had the spinnaker up some of the time. That was the shortest daily run of the circumnavigation until 10 days later we had a day’s run of only 14 miles.

There were times when if I could have ended the passage I would have, but I couldn’t, so I carried on. In an absence of joy, there is much to be said for honor and perseverance. And once completed there is the satisfaction of having gone the distance and accomplished something difficult.

Gannet’s daily runs for the entire circumnavigation total 29,989. I think it fair to round up to 30,000.

Don’t forget to pick up the June issue of Latitude 38 for a feature on Webb Chiles’ sixth circumnavigation.

US Coast Guard Water Safety Fair

About those SailGP F50 Cats

As the French SailGP team wrote in their latest press release, “Il fait frisquet à Frisco.” They’re comparing the relatively mild conditions for the first act of the series in Sydney to the brisk conditions in the Frisky City for the second act this weekend. This afternoon’s activities will center around official practice racing. Fleet racing on Saturday will lead up to a match race between the top two teams on Sunday.

The Crews

On Media Day, SailGP’s Tom Herbert-Evans served as announcer, calling play-by-play and answering reporters’ questions. He explained the five onboard crew positions: “Starting from the stern, the first person you’ll encounter is the helmsperson, the driver. The next person is the wing trimmer. The third person is the flight controller, who’s fully focused on the maneuvers, the tacks and the jibes, keeping the boat entirely clear. If you see one of the boats crash down, that’s because of a lack of coordination between the driver and the flight controller — or the sea state going into the maneuver. Up front you have grinders. They’re actually trimming some other systems onboard, as well as turning the drum that controls the wing sheet. For America’s Cup 34 in San Francisco, there were about 13 crewmembers. There were a lot of people pumping the hydraulics that move the big hydrofoils up and down in the last event. This time all those are battery-operated.”

The need for brute force has been diminished from the last two America’s Cups, but only one team has a woman onboard. Olympic gold medalist Marie Riou serves as flight controller for the French team. Riou, you may recall, crewed on Dongfeng Race Team, winning the last Volvo Ocean Race.

“The posture of the sailors, when they’re standing more upright in the boat, it means they’re more comfortable. When they’re crouching down, it means they’re holding on for dear life. When they’re going upwind, they’re experiencing about 60 mph of apparent wind. Kind of like putting your head out the window on the highway. So they crouch down to try to get rid of the aero drag as well.”

Foiling 50-ft Catamarans

SailGP’s weapon of choice is no ordinary beach cat. These are two-ton, true one-design remodels of the craft used in the last America’s Cup. “The platforms and wings are from the AC50, though essentially everything else is different,” explained Christy Cahill, SailGP’s director of communications. “Two boats were built from scratch.”

“Between events, if the teams think they can improve something onboard, they’ll give that feedback to their team heads and then back to the event itself, and they’ll collectively make those improvements,” said Herbert-Evans. “Unlike the America’s Cup and some ocean races that have secretive developments, with SailGP everything is open. We share all the data. If a team’s not doing too well, they get full access to the data. All the boats are identical.

“One of the major improvements is they changed the control system. Now there’s a lot more responsibility on the flight controller. It’s kind of like they’re flying an airplane, but purely using the water to keep the boat hovering, which makes them as fast as possible. You can see the kind of black daggerboards on each boat sticking out of the boats. There are two white lines on them. They’re trying to use those white lines to gauge the safe limits of where they can hydrofoil. If they get too high, you’ll see them have a mega crash and come down splashing into the water. If they’re too low they just go very, very slow. So it’s a fine balance as to what you want to achieve — safety, or getting around as quick as possible.”

Observing the conditions on Tuesday, with wind velocity reaching perhaps 20 knots, we wondered about an upper wind limit. “Next year, we’re going to have an adjustable wing, so we’ll actually be able to go from 18 meters to 24 meters to 28. So we’ll be able to sail in a broader range of conditions,” explained Cahill. “We would just go down to the 18-meter wing if the wind was stronger and up to the 28 if it was really light. If we’d had those in Australia, we would have used the bigger 28-meter wing. These wings are 24 meters — 78-feetish.”

“The wings themselves are a hollow structure glazed over with this material that forms this really light, rigid shape,” said Herbert-Evans. “The main wing can be compared to an airplane wing. The jib is a very small triangular sail. That just drives a bit more horsepower and helps with tacking and jibing. By having a sail in front of the wing, it hyper-accelerates the wind as well.” Much like many race crews on San Francisco Bay, they have three different sizes of jibs from which to choose, depending on conditions. They’re self-tacking. “The jib is a little handkerchief today,” said Tom on Tuesday.

The teams’ target is to get around the course foiling 100% of the time, but they’re doing superbly well if they manage it for 90% of the race.

“There are two ways I’ve seen the boats come potentially close to capsizing. One is if their rudder elevators come out of the water. There are two little winglets at the back of the boat. If the back foils come out of the water, the boat will nosedive, potentially through a catapult. The boat comes to an absolute stop. The G forces are pretty major.”

This is what happened to the Chinese team’s boat during the postponement between races on Tuesday. Their bows pearled, they came to a full stop, and their wing tried to keep going. Thanks to the efforts of the shore team, China is expected to be back out on the water today.

“The second way is going upwind if they come out of a foiling tack attempt too quickly. It can be quite difficult to manage, and they kind of tip over. But the guys have put a lot of time into safety. All the sailors are now tethered up. If the boat does capsize, there’s a short piece of Spectra that they’re tethered on with. They’re trained to go into the hull where there’s a breathing hole. They’ve got a safety diver following as well.” Each team has its own chase boat, as the potential exists for multiple capsizes.

The 50-Knot Barrier

“San Francisco is an incredible venue because the wind is so consistent,” continued Herbert-Evans. “There’s high average wind here, which is great for hitting the 50-knot barrier, but difficult for the crews keeping the boats under control. The reach is the fastest point of sail. That’s where you’ll see the 50-knot barrier broken.” The Australia team has gone the fastest, hitting 49.7 knots.

“The hydrofoils have a high- and a low-pressure side built into them. This creates a Bernoulli system of lift, like an airplane wing. The problem is, if it develops too much low pressure on one side, water actually boils. Kind of like when you’re on the top of a mountain, the boiling point is a lot lower. That creates air along the foil surface, and the foil doesn’t know what’s going on anymore, so it stalls out, and the boat will typically drop off the hydrofoils. With air along the surface, it’s no longer a hydrofoil, it’s an airfoil. When you see them crashing at high speeds, that can be the cavitation, which is something that’s come to light recently, preventing the teams from hitting that 50-knot barrier. It’s comparable to the speed of sound on a jet. There is a boat that’s done 65 knots on the water, the current world speed record, but that boat can only go in one direction, and it’s designed to be on very flat water, in very controlled conditions.”

The Racecourse

The racecourse features windward and leeward gates, allowing the teams to split after the start — the course has two sides. This configuration makes it possible for boats to catch up and to stay out of the dirty air of boats in front of them by choosing a different side.

Nathan Outteridge, skipper for the Japanese team, told Don Ford of KPIX: “When you have a bad start in a match race, you’re only going to be a length or two behind the first boat, and you have the opportunity to tack all the time, whereas in a fleet race, if you have a bad start, you’re in traffic. The second through fourth boats are very close together. The first boat gets away. Starting is important.”

“The course will most likely remain very consistent as to format,” said Herbert-Evans, “but it will compress on its length. If the wind was a little bit lighter, we’d have a much shorter racecourse. To try and keep within our broadcast window, we’re trying to keep the races around 15 minutes. Iain Murray, our principal race officer, will have already calculated a rough average for getting around the course.”

We’ll have coverage of the actual racing in Monday’s ‘Lectronic Latitude and in the June issue of Latitude 38.

Why You Should Have an EPIRB

Hello readers! My name is Layne Carter and I am your friendly Coast Guard Search and Rescue (SAR) Specialist at the Coast Guard’s Joint Rescue Coordination Center (JRCC) Alameda. Every Coast Guard District has a SAR Specialist like me who is charged with being the regional SAR subject-matter expert. My counterparts from the other nine Coast Guard Districts and two Rescue Sub-Centers (Guam and San Juan) and I provide policy guidance, observe trends, monitor emerging technology, and generally advise our military counterparts on all things SAR.

At JRCC Alameda, we coordinate quite a few rescues involving EPIRBs (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons) in the sailing community. So what better topic to start with than a little overview of SARSAT and how the Coast Guard utilizes this system to help save lives every day? What is SARSAT? SARSAT (Search and Rescue Satellite Aided Tracking) uses a network of satellites, ground stations, mission control centers, and RCCs (like JRCC Alameda) to detect beacons (EPIRBs, PLBs, and ELTs), so we can send rescuers to your aid. It is a free, humanitarian service that only requires you to own and properly register a beacon. There are no registration fees, no fees for a rescue, and the system is monitored 24/7 at no cost to you. It is a global effort to ensure that if you are in peril and activate this device, someone will be looking for you.

So far this year, 38 people have been rescued at sea thanks to SARSAT. Globally, more than 43,000 people have been rescued since 1982. What does that mean to you? It means this system has been around a long time, and with time comes experience. (All statistics I post in this article refer to the NOAA SARSAT web page at www.sarsat.noaa.gov.) Between NOAA, the US Air Force, the US Coast Guard, and our global SAR partners, we have learned a lot about SARSAT and have been applying that experience and lessons learned to every part of the process from technology to search methods. Today’s SARSAT program is light-years ahead of where it was even 10 years ago and is only getting more accurate and efficient every day.

Let’s talk about the technology. It is important to know what your beacon is capable of doing and what it cannot do. Will it activate when immersed in water? Will it automatically include a GPS-encoded position in the first signal sent to the satellites? These are important factors to consider as they greatly aid in our ability to get help to you when you need it most. Personally, I use a beacon that activates when it hits the water without any human intervention. If an unexpected tragedy strikes and my boat goes down before I can reach that EPIRB or PLB, I have a sense of comfort knowing my self-activating EPIRB will get the word out, even if I am not able to do so myself. In addition, it sends an encoded GPS position, which reduces the time it takes for rescuers to find me.

New beacon technology is on its way! Second-generation beacons are being developed as we speak and should reduce cost, increase accuracy, and potentially provide additional capabilities such as AIS plotting and return link service (RLS). RLS will allow the individual activating the beacon to receive a notification when their alert has been received, among other potential benefits. So keep your eyes out for these second-generation beacons. (I do not have a solid timeline, but I anticipate we should be seeing them hit the market sometime within the next couple of years.)

So what happens when you activate your beacon? The device sends a very powerful signal up to our anxiously-awaiting satellites, where it is then routed straight to the RCCs without any human intervention. There are currently three constellations up there, LEO (Low Earth), MEO (Mid Earth) and GEO (Poles). Each satellite constellation serves a specific purpose and processes the information it receives differently. LEOs use the Doppler effect to determine a position. GEOs just relay the fact that a beacon has activated and if it is registered it will include contact information, while MEO uses trilateration, which is super-fast (under a minute) and very accurate. More details on the satellites and their capabilities can be found NOAA’s page, mentioned above.

Once an RCC — like JRCC Alameda — receives the alert, the SAR mission planner evaluates the information to determine the level of response. Depending on the satellite that receives the alert and the quality of the signal received by the satellites, the initial position may not be received or may be unreliable. For this reason, we rely heavily on the details provided in the registration information that we receive with the alert. We will attempt to call you or your emergency points of contact to determine if you are underway or if your boat is sitting at the pier. If we have a position in a maritime environment, we are making one or two calls to your primary contact numbers and launching an asset immediately (usually simultaneously). It is important to remember that launching an aircraft or a boat in response to a perceived emergency is inherently dangerous. Our coxswains and pilots assume a certain amount of risk every time they launch, so if you accidentally activate your beacon, it is crucial you let the Coast Guard know as soon as possible.

More often than not, if we receive a bad position (unreasonable for the type of vessel or terrain, e.g. a small helicopter 1000 nautical miles west of California) or no position at all in the initial alert, it is likely because the beacon is being shielded by a structure of some sort or in a garbage dump. In one case, an EPIRB was donated to a local watering hole and was hanging next to the bar where patrons could turn it on and off to see pretty lights flashing. We will spend a significant amount of time trying to track down the owner using the information provided on the beacon’s registration, coupled with publicly available information to generate leads.

So keeping that registration information current is very important. It is worth mentioning that only the US Coast Guard and NOAA can access the emergency contact information. We take your privacy very seriously, and restrict access to the database to SAR mission planners in the US Coast Guard.

I will finish with one final point. We treat each alert as if it were a member of our own family letting us know they need our help. So when you are out enjoying the tranquility, beauty, and freedom boating has to offer, know that no matter where you are — if your EPIRB, PLB, or ELT is activated in the maritime environment — the people in the world’s finest Coast Guard will be doing everything in our power to get help to your location. Help us help you! Keep your registration current, notify us if you accidentally activate your beacon, and give us a call if you have any questions. We are passionate about saving lives and welcome your questions 24/7.

If you have any questions, you can email Layne Carter here.