Caption Contest(!)

This month’s Caption Contest(!) is a real doozy. Last summer on the Chesapeake, these two boats got all up close and personal. We’ll have the full story, as well as this month’s CC(!) winner in the November issue of Latitude 38.

PLEASE SEND YOUR ENTRIES HERE! (Sorry, we originally forgot to include the link . . . and then we got a new website!)

The Autopilot

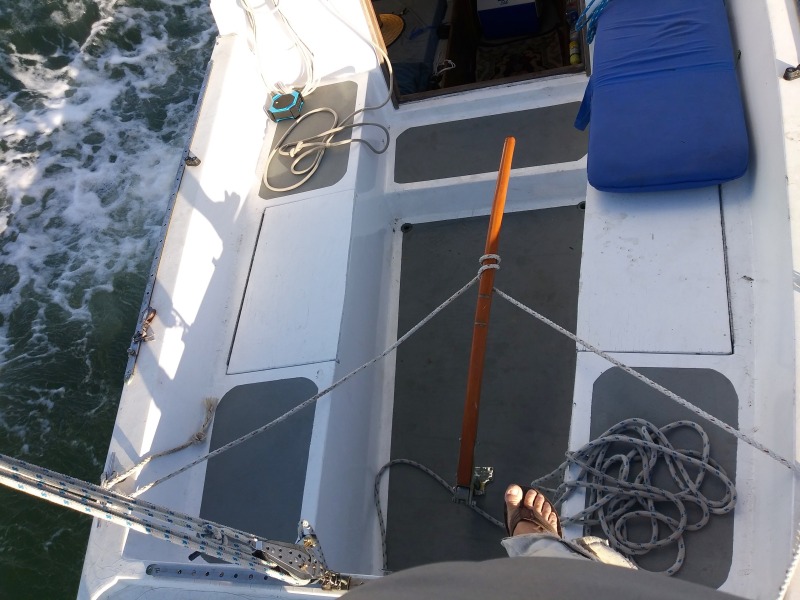

Nothing brings me greater pleasure than tying off the tiller during a singlehanded sail, sitting back, and watching the boat work.

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

On Saturday, there was way more breeze than I’d expected coming out of the San Rafael Channel. I was able to raise sail before the Marin Islands, but instantly had my hands full — admittedly, I had not prepared my Columbia 24, Esprit, (namely my gear below deck, including my computer). I was neither physically nor mentally ready for the conditions, and was a little indignant that it had decided to be so windy. I beelined for China Camp.

My first singlehanded anchoring was way easier than expected (so many sailing ‘challenges’ are easily demystified simply by doing them). Once on the hook, I was able to ready the boat. I’ve come to deeply enjoy what I’ll call the at-anchor ‘putter’, doing dozens of tiny chores that would never get done in any other context. As Esprit thrashed around on the hook, the wind — which had been moaning through the rigging — started to scream, just a little.

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

After I’d reefed the main and weighed anchor, the boat was a different beast. With one wrap just forward of center on the tiller, my Columbia sailed easily upwind by herself. I sat on the companionway hatch, stood on the transom, and crawled to the bow to just . . . watch the boat, sailing 70% of the way back without touching the tiller, and able to make fine-tune adjustments with my body weight. I simply cannot describe the sensation and sense of freedom that powering to weather on a primitive autopilot elicits. It’s a completely different type of sailing altogether.

© Latitude 38 Media, LLC

Do you have any special ‘autopilot’ techniques? We’re strictly talking bout tying the tiller or wheel here. Do you get giddy like a little kid when you step back and watch your boat sail? We’d like to know.

Ad: KKMI Is Hiring

Salvage, Part 2

Picking up from Part 1 on Friday. After one of their Pearson 26s went missing (along with the skipper), the staff at Club Nautique eventually found the boat hard aground at Baker Beach, just outside the Golden Gate. They decided to try to salvage the vessel, using Squirrelly, an underpowered, 42-ft Albin trawler, to try to tow the boat off the beach.

Squirrelly, anchored to the shore by a boat full of sand and saltwater, was in an awkward position, buffeted by a rising crosswind reinforced by the gathering tide. The black rocks to leeward were sharp as broken teeth. A Coast Guard 36-ft motor lifeboat held station just beyond the rocks. They were there for rescue, not salvage.

The yard boss launched his dinghy from the shore, paddling ferociously with a piece of broken plywood. He made it through the first breaking wave but not the second. The entire flat bottom of his dinghy was visible as it climbed the wave, hung suspended for a heartbeat, then gracefully succumbed to gravity, falling backward. When we finally got him back onboard he was shivering from hypothermia. His lips were blue.

Slowly I took a strain on the hawser. The slack line snaked through the water and grew taut as a wire halyard, wringing salt water from the strands of nylon. Smoke belched from the trawler’s exhaust pipes as I advanced the throttles. Her stern squatted under the load. We swung through a 70-degree arc like the plumb bob of a pendulum. Slowly the Pearson pivoted on her keel. Her bow swung into the surf. She shifted slightly, the trawler surged forward a foot, and the hawser snapped. The yard boss looked distraught.

The entire dumb show was repeated. Once again the yard boss paddled ashore. Once again Squirrelly was wreathed in her own smoke. Once again the Pearson remained immobile.

"Give it all she’s got," Fred yelled, standing beside me on the flying bridge. I ran the throttles full forward. The hawser stretched another three feet, then once again parted. 200 feet of half-inch line was abruptly released from tremendous strain, like an arrow released from a bow. We were the bullseye.

Fred dropped to the deck like a stone. I stood, a deer in the headlights, while 200 feet of half-inch line drove into the trawler’s transom with the staccato sound of an M-60 machine gun. The towing hawser then fell into the racing props. The props were immediately fouled. Both engines seized and died as if they’d been cold-cocked. Immediately we began drifting toward the rocks to leeward.

The beleaguered yard boss, still shivering, was sent over the side again to clear the props. The rat’s nest was tightly wrapped around the shafts, each wrap levered tight by hundreds of pounds of torque. Each wrap had to be sawed apart with a knife. The yard boss, working almost blind, submerged in the cold, boisterous water. Every time he surfaced, with every breath he took, he could see the rocks drawing closer. The Guardsmen on their motor lifeboat began to fidget.

The starboard prop was freed. I didn’t dare start the engine with a man in the water. We drifted farther, driven by wind and current. The Coast Guard motor lifeboat began to position themselves for our rescue when the yard boss broached the surface with thumb raised high. The crew plucked him out of the water like a crab buoy. I fired both engines and throttled up, swinging the boat away from the rocks.

We abandoned the wreck and returned to the bay. A professional salvage crew would refloat her in a day or two. The insurance company could pay for the job and be damned. We were cold, wet and disgruntled. Fred offered to buy us all dinner.

It was a singular act of generosity but, typical of Fred Sohegian, one with an odd caveat. He was taking us to dinner at the St. Francis Yacht Club.

The St. Francis was one of only two places left in the United States (the other being the New York Yacht Club) where gentlemen still wear blue blazers and a tie for dinner. We trooped through the dining room wearing frayed foul weather gear, crooked grins, hair in wild disarray, with salt stains streaking our cheeks. Heads turned, eyebrows raised, and the disapproval was palpable. Fred was wonderfully amused.

For several months after our dismal salvage attempt we assumed our missing charterer had been lost overboard while sailing solo that night, his body carried out to sea by the ebb. Singlehanded sailing was strictly forbidden by Club Nautique’s rules but we still felt culpable in the tragedy. Then we got a call from the Club’s insurance company. Our drowned man was in Canada.

It seems he had gotten so deeply in debt that his crack-brained solution was to fake his own death. His insurance policy would pay his wife. But the drowned man had underestimated his loneliness and his family’s unbending righteousness. He called his father long distance (collect, I suspect) and explained why he was not dead. His father, a devout member of the Church of Latter Day Saints, praised the Lord and called the police. The police eventually called the insurance company who finally called us. It had all ended badly.

The Pearson, refloated and repaired, was returned to service. Turns out, they actually are bulletproof.

Destination Drake’s Bay

What a difference a Bay makes. This past weekend we joined our friends, Randy and Jennifer Gridley, for a weekend ‘sail’ up to Drake’s Bay aboard their Sabre 38 Aegea. The forecast was good and the local destination ideal for a weekend great escape. The only thing missing was the sail part. Regional forecasts were for nice winds on the Bay and light winds everywhere else. However, it still made for great day for whale watching and fishing.

© Latitude 38 Media, LLC

We left Sausalito at a relaxed 10 a.m., hoisted the main, and motorsailed to the Golden Gate hoping to find some breeze as the fog burned off. Neither happened. The fog and calm seas remained for the entire 6-knot, 5-hour motorsail to Drake’s Bay. Nonetheless Marin’s dramatic coastline provided a fabulous backdrop, and whale sightings became so frequent they seemed like deer in our yard. They’re always cool to spot, but the excitement diminishes while you keep your distance.

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

We anchored in 17 feet of water in the calm, protected waters behind the southern hook of Point Reyes that forms Drake’s Bay. The holding was good and the anchorage protected, making it a relaxing cruise to this nearby yet ‘remote’ destination.

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

The following day we left at a comfortable 9:30 a.m. with light breeze and flat seas. Clear sun showed up at about 11, but enough wind to get us home by the end of the day never materialized. We sailed for about an hour before we finally reverted to motorsailing, along with about four other sailboats in sight that we imagine are coming in from the north on their way to Mexico. It’d be nice to join them.

©2018 Latitude 38 Media, LLC

We neared the Golden Gate after crossing a mill pond above the Potatopatch and watched the wind build as we joined boats enjoying a brisk sail on San Francisco Bay, the site of the only wind we saw the entire weekend. It was a great trip and reminds us of the unique sailing conditions created by the Coast Range and the single cut through it at the Gate. Offshore can be calm and peaceful while the conditions in the Slot are like the air escaping from the balloon of the entire Pacific Ocean.

Yes, what a difference a Bay makes. Just about any weekend you can find the conditions you desire. Great breezes to rip across the Bay, calm and warm behind the headlands or in the Estuary, or great destinations if you decide to venture offshore or farther inland to the Delta. It’s a sailors’ paradise with plenty to explore.